Most investors misunderstand—or maybe “over-simplify” is the right term- Relative Strength (RS). I think a big part of the problem is the inherent desire to make RS sound more simple and basic than it really is. Simple processes are easier for a novice to understand and accept as a viable investment strategy. From the standpoint of the expert talking to a novice this is preferable because a novice doesn’t have the time or inclination to learn all of the complexities of the strategy. In other words, a novice doesn’t need to know how to build a watch; they just need to know how to tell time.

The reality is that RS is much more complicated than people actually think. When we talk to advisors they are often under the impression that a strong stock is a strong stock and there is only one way to measure strength. It just so happens that the best measure of momentum, according to whoever you are talking to, is the method that person has been using lately! RS is much more complicated than that. There are numerous ways to measure the strength of a stock.

It is no different than a value strategy. If you ask a room full of value managers what defines a “value stock,” you’re going to get a room full of answers. Some people define value in terms of dividend yield, while others might use a price-to-cash flow model. If you look at the portfolios of these two individuals, they are going to have different holdings even though they are both buying “cheap” stocks. More importantly, the portfolios are going to perform differently during different parts of the market cycle. The market rewards different factors to different degrees at different times. Both factors might outperform over a long time horizon, but over any short time period the performance might be dramatically different. There is nothing wrong with this! If the dividend yield manager underperforms the cash flow manager during a given time period, it might not have anything to do with the skill of the two managers-it might simply be a matter of the market rewarding different value factors at different times.

Just as there are numerous value factors, relative strength can be calculated in many different ways. Even something as straightforward as point & figure relative strength has numerous calculation methodologies. You can use a 3.25% box size, 6.50% box size, the old Chartcraft standard boxes, a matrix (using any box size you want), or anything else you can dream up. You can also favor an RS column change, and RS buy signal, or some combination of the two. Dorsey Wright doesn’t even advocate one superior calculation method, as the research database makes all of these different calculation tools available to you. The market will reward these different RS factors at different times. Sometimes short term strength is rewarded more than long term strength; sometimes it’s the other way around. It is no different than the value stock example discussed above. If one person uses a 12-month price return model to measure RS and another uses a 3-month price return model, their portfolios are going to hold different securities, have different turnover, and performance might be completely different during any given time period. Both managers are using relative strength and buying strong stocks-they are just defining RS slightly differently.

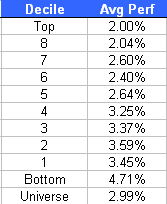

For example, take a look at how several different RS calculation methodologies performed during the first 6 months of 2009. As part of our research and ongoing process of continuous improvement, we track lots of RS factors in the Money Management office (besides our own proprietary measurement). Here, we are just using some simple price-return-over-time models to illustrate our point.

The data in the table above shows that the way you define relative strength leads to very different return profiles over short time periods. All of these models outperform the broad market over long periods of time (we do have the data on that!) so they are all acceptable ways to determine strength. However, over half a year the market has rewarded each factor very differently.

In addition to the variation in returns between RS factors there will also be variation in returns within an RS factor model. Unless two managers buy the entire basket of high RS securities, their portfolios are going to look different. This may seem obvious, but it is something many people don’t consider when evaluating an RS strategy. While the chosen factor might be robust enough to deliver market-beating returns over time, any sub-set of the high RS basket might perform better or worse than any other sub-set over a given time period. There can be massive variation between portfolios, even ones using the exact same RS factor. Here, we use 100 different random trials to give you some sense of the possible variation. The following table illustrates this point.

Using exactly the same factor, your returns could range from -21% to +8%, depending on which stocks in the group you ended up with.

We use a unique and robust testing protocol here in the Money Management office. We try to make everything as “real world” as possible. In a paper our portfolio staff wrote way back in 2005, we designed a random trade process that allowed us to randomly select high RS securities for a concentrated portfolio. The theory is this: if you can select stocks at random from a predefined sub-set of a universe and still outperform a benchmark over time you have a remarkably robust process. That random trade generation process was used to test the model in the table above. You can see that with the same parameters and same investment universe there can be wildly different results over a short time period. Over a longer testing period (1995 through mid-2009) all 100 random trials of the simple 6-month model outperformed the broad market. But over a short period of time, it is quite possible to get stuck with a low-probability, lousy outcome. (You can even get quarters where about half the trials outperform and half underperform.)

There is a tendency for investors, when they get stuck with a lousy outcome, to believe the process is broken. It isn’t. Most people want to believe they are in control of every situation so having to think in terms of probabilities often makes them uneasy. However, it’s the reality of investing: not just in an RS strategy, but in every other strategy as well.

As you can see, there is variation in relative strength strategies just like there is variation in returns with every other investment strategy. There isn’t one right or wrong way to calculate RS, although we do know that some ways are better than others! (We happen to be fans of our proprietary method.) Every calculation methodology has strengths and weaknesses. Both the strengths and weaknesses will be exposed at some point during the market cycle. There is no way to avoid this phenomenon. There is no magic unicorn that’s going to appear and tell you the best way to identify a strong stock this week—and it will change next week anyway. You’re better off to stop looking for the unicorn and spend your time testing for a robust method that will work over a long period of time, and then understanding everything you can about the tradeoffs you are making. Our bias is to use exhaustive testing and data analysis to investigate and make decisions about the tradeoffs we need to live with. Perhaps not everyone has the resources and programming ability to make that feasible, but you can spend time thinking about how your factor is constructed and where it might be vulnerable. There are very few guarantees in finance, but I can make this one: if you truly understand everything about the statistical parameters of your process, the next time someone tries to tell you your model is broken, you might have a knowing smile instead of a concerned frown.