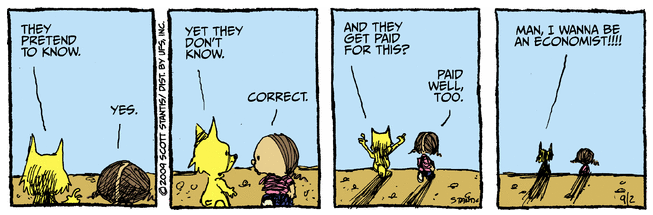

In an amazing article that appeared in the Sunday New York Times, Paul Krugman presents his thoughts on how economists got it so wrong. In short, they believed the Capital Asset Pricing Model and in efficient markets. You’ve got to read the whole article to get the flavor of the amazing fantasy world he describes. He writes:

To be fair, finance theorists didn’t accept the efficient-market hypothesis merely because it was elegant, convenient and lucrative. They also produced a great deal of statistical evidence, which at first seemed strongly supportive. But this evidence was of an oddly limited form. Finance economists rarely asked the seemingly obvious (though not easily answered) question of whether asset prices made sense given real-world fundamentals like earnings. Instead, they asked only whether asset prices made sense given other asset prices. Larry Summers, now the top economic adviser in the Obama administration, once mocked finance professors with a parable about “ketchup economists” who “have shown that two-quart bottles of ketchup invariably sell for exactly twice as much as one-quart bottles of ketchup,” and conclude from this that the ketchup market is perfectly efficient.

Interspersed with some really fascinating background information on warring factions of theoretical economics, Krugman concludes that the possible future of economic theory will veer more toward behavioral economics.

There’s already a fairly well developed example of the kind of economics I have in mind: the school of thought known as behavioral finance. Practitioners of this approach emphasize two things. First, many real-world investors bear little resemblance to the cool calculators of efficient-market theory: they’re all too subject to herd behavior, to bouts of irrational exuberance and unwarranted panic. Second, even those who try to base their decisions on cool calculation often find that they can’t, that problems of trust, credibility and limited collateral force them to run with the herd.

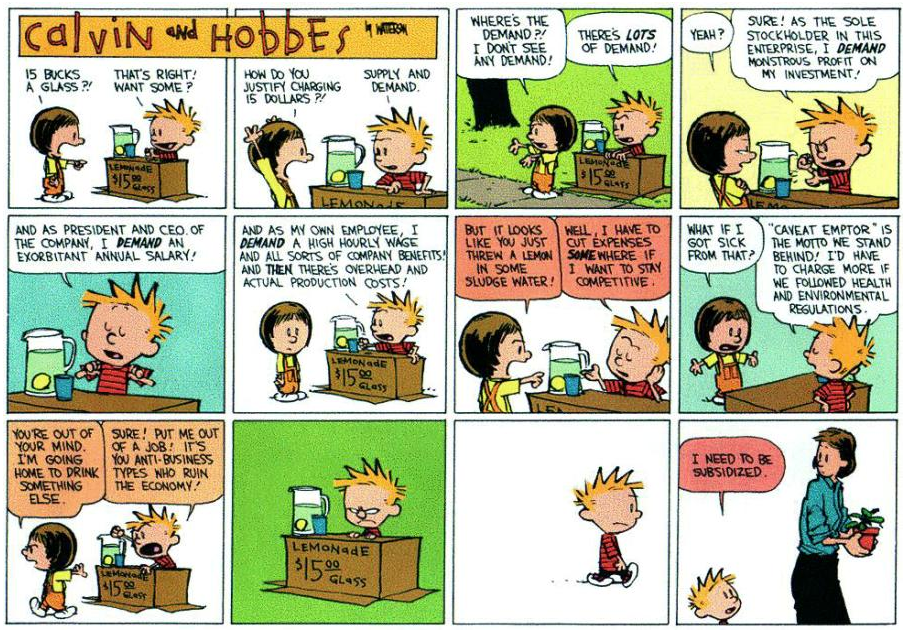

Hmmm. Exuberance, panic, running with the herd? If you think herd-following sounds suspiciously like trend following, you are right. It turns out that perhaps prices are driven by supply and demand, even when (or especially when) investors are subject to exuberance and panic.

Theories turn out to have consequences if you mistake them for reality. Efficient markets turned out to be as real as the tooth fairy. Everything seems to boil down to supply and demand, where periodic imbalances-for whatever reason-create trends. Our Systematic RS family of accounts is simply an adaptive, unemotional way to navigate markets that turn out to be all too human.

Posted by Mike Moody

Posted by Mike Moody