What good is Christmas if Santa can’t get in trouble with the World Trade Organization?

The Yield Curve Yells for Attention

December 17, 2009With all of the fuss about the costs of healthcare reform, the TARP, the pros and cons of more economic stimulus, and Bernanke’s reappointment, economists seem to have taken their eye off the yield curve. I haven’t read much commentary about it at all. That’s unfortunate because the steep yield curve has a pretty dramatic message right now.

FTAlphaville has a nice article on the yield curve today that includes the graphic below:

This particular yield curve is constructed with the U.S. Treasury 2-year/10-year spread, and the spread is now at an all-time high.

It turns out that the yield curve is one of the best, if not the best, predictors of economic activity, recession, and inflation down the road. The forecasting record of the yield curve, for example, is much better than the record for various panels of economists. (For the New York Federal Reserve Bank’s FAQ on the forecasting properties of the yield curve, click here.) Pimco has a primer on the yield curve on its website which states:

A sharply upward sloping, or steep yield curve, has often preceded an economic upturn. The assumption behind a steep yield curve is interest rates will begin to rise significantly in the future. Investors demand more yield as maturity extends if they expect rapid economic growth because of the associated risks of higher inflation and higher interest rates, which can both hurt bond returns. When inflation is rising, the Federal Reserve will often raise interest rates to fight inflation.

At the conclusion of the Fed meeting yesterday, they voted to continue the policy of keeping short-term rates low. As a result, we may see the yield curve continue to steepen. Most economists (and stock market investors) are counting on a sluggish recovery—but that’s not the message the yield curve is sending out. If the yield curve is correct, we could see much higher economic growth and much more inflation than is built into the consensus forecast.

A pundit once wrote that economists were invented to make witch doctors look good. Fortunately, I am not an economist and I have no idea what will happen to the economy going forward. However, from an investment perspective, I am quite aware of the dangers of building an asset allocation based on a wildly incorrect economic forecast. U.S. investors, by plowing enormous amounts of money into bonds and bond funds this year, are implicitly endorsing the consensus forecast of slower growth. The yield curve is saying that could be a big mistake.

As unlikely as it seems, what happens if we have powerful economic growth and rising inflation over the next couple of years? For a baby boomer nearing retirement with a portfolio loaded with fixed income it might be pretty painful. It may be that commodities or inflation-indexed securities—or another asset class entirely—will work out better. A more tactical approach to asset allocation removes the need to guess about what will happen and allows the investor to react to conditions as they change.

Posted by: Mike Moody

Capturing Trends

December 16, 2009Intuitively, investors feel like the more nimble they are, the better they will do. They put tremendous pressure of themselves to capture every wiggle in the market. Yet, much of the time, going faster is counterproductive.

In this blog post, “Understanding How Markets Move,” noted psychologist and trader Brett Steenbarger uses the simple example of a moving average system applied to the S&P 500. The more you speed up the moving average, the worse it does. That seems counter-intuitive, but you have to keep in mind that trends are what make money and trends are often slow. The faster you go, the more noise you capture, and thus, the worse you do.

We find exactly the same process at work when using relative strength. Reacting to short-term relative strength does not perform well over time. The best-performing models follow intermediate to long-term relative strength—and just tough out the periods that are rocky. Many clients have trouble sitting still when going through a rocky period, but as Steenbarger points out in his post, you have to deal with the asset you’re trading. Stocks have their own time frames for trends and an impatient investor isn’t going to speed it up. If you want to trade financial assets, you have to work with them on their own terms.

Posted by: Mike Moody

Sovereign Wealth Funds: We’re Dumb Money

December 16, 2009I guess it should come as no surprise. There’s lots of data that shows retail investors and institutional investors make, in aggregate, lousy investing decisions. They buy near the top, they sell near the bottom, they hire hot managers that soon become cold, and fire cold managers that soon become hot. But sovereign wealth funds are in a unique position to be able to buy and hold long-term assets—or at least you would think so.

It turns out, according to a Reuters article, that they have the same problems as everybody else, even according to them.

“We’re not different from any other asset managers. The notion of being a long term investor does not mean you discard the main rationale for any investment. There is tremendous pressure on an institution like us (to make profit), because we belong to our people,” Israfil Mammadov, chief investment officer at Azerbaijan’s sovereign fund, told Reuters.

In fact, it might even be worse. Imagine if an investment manager had Congress breathing down their neck! Can you imagine the grillings before the committee? But that’s what can happen in a sovereign wealth environment:

“In practice, the notion that SWFs are more patient than private investors does not really hold water. SWFs often face the same horizon as other market players, and are subject to the same exigencies — they need to maximise return for their shareholders,” an advisor to an Asian SWF told Reuters.

“And governments can be even less patient than private investors. SWFs pursue industrial goals of the government that can be quite pressing. They are operating under very tight schedules.”

Individuals that purse a flexible, well-thought-out systematic investment process are just as likely to do well as any institution or sovereign wealth fund. Don’t underestimate how much factors like patience and unemotional decision-making can help your investment results.

Posted by: Mike Moody

More on Target Date Funds

December 16, 2009Ah, target date funds were such a simple concept. Buy the fund for your projected retirement date and let the glide path guide you to a rosy retirement. It was the ultimate set-it-and-forget-it investment product. Who wouldn’t want that?

In practice, target date funds have run into all sorts of complicated hurdles.

1) Consumers didn’t know how to use the funds and so bought multiple target date funds in the same account, combined target date funds with a bunch of other active funds, or traded in and out of target date funds on a short-term basis.

2) The glide path turned out not to be fixed. Some investment committees tinkered with the asset allocations of the funds from time to time, so consumers were never completely sure what they were getting. The allocations also varied widely from provider to provider, based on different assumptions for returns, risk, and appropriate allocations for retirees.

3) When even 2010 target date funds took a beating in 2008, consumers discovered that the strategic asset allocation process embedded in the funds hadn’t done very much to protect their retirement assets. Almost universally, consumers expected the funds to be much more conservative when only two years from their retirement date.

4) The logic of allocating more and more to fixed income as the fund holder nears retirement is questionable. Yes, bonds are typically less volatile, but there’s no guarantee that will be the case. And piling more assets into bonds at today’s near-zero interest rates doesn’t necessarily seem like a clever idea.

And now this: it turns out that a substantial part of the fixed income allocation in some of the target date funds—and keep in mind that the fixed income allocation expands as retirement nears—is composed of low-rated, high-yield bonds. Probably not what the soon-to-be-retiree was expecting.

Frankly, some of these items are not the fault of the target date fund at all. There’s nothing wrong with high-yield debt as an asset class, for example. Consumers should do some due diligence and know what they are buying and how to use it properly. On the other hand, the marketing of the products sometimes gave the impression that everything would be handled for you.

Here’s a way to avoid most of these problems entirely: tactical asset allocation. Instead of assuming that it’s always good to own more bonds as you get older, how about investing on the merits of the individual asset? To me, the tactical approach just makes much more sense. Own stocks and other risky and higher-potential assets in environments when risk is being rewarded and switch to fixed income and other lower-risk assets in environments when risk is not being rewarded. Tactical asset allocation does require constant monitoring and adjustment, but it could turn out to be well worth it.

Posted by: Mike Moody

Laggard Rally Progression

December 15, 2009The laggard rally of 2009 has been the second largest in history. Only the massive laggard rally off the market low in 1932 was larger (and by a substantial amount!). Doug Ramsey of The Leuthold Group (http://www.leutholdgroup.com) published a great study in their December 2009 Green Book that addressed laggard rallies in relation to market drawdowns. His thesis is that the larger the market drawdown, the larger the laggard rally.

Doug was kind enough to help me sort through the source data they used for the research (6 Portfolios Formed On Size & Momentum on Ken French’s website) so I was able to recreate his results, which are shown below.

(Click To Enlarge)

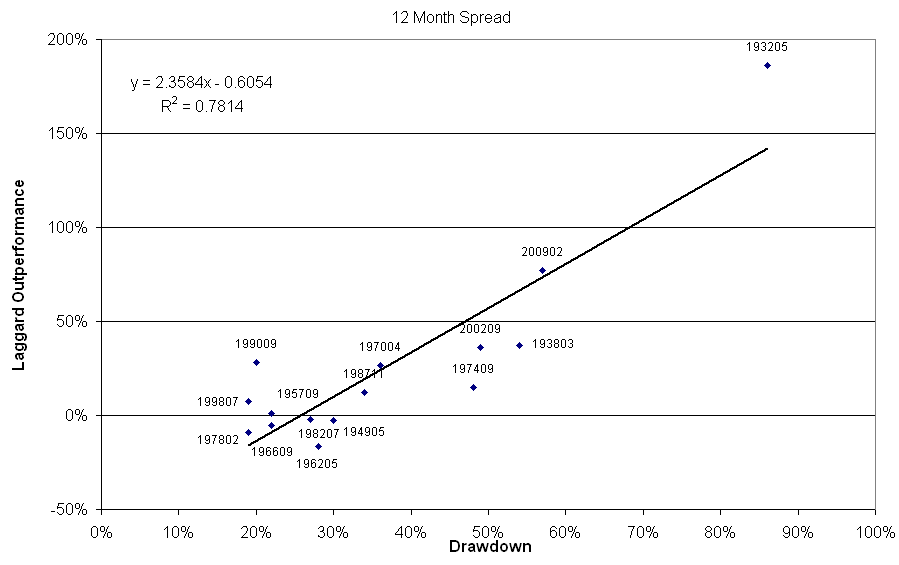

The chart above measures the market drawdown on the horizontal axis, and the amount of the laggard outperformance over 12 months on the vertical axis. You can see the very strong relationship between drawdown and laggard outperformance. The laggard rally from the lows of the most recent drawdown are basically sitting on the regression line. In terms of the fitted model, this is about what we should have expected.

The striking relationship between drawdown and laggard outperformance got me thinking. We are always on the lookout for a reliable regime switching methodology that can reliably predict these periods of laggard outperformance. We have tested a lot of ideas, but nothing ever seems to improve the performance of simply sticking with the winners over the long haul. I broke the performance of the laggards out into multiple time periods to see how the laggard rally unfolds over time. The charts below show what happens over the first three months from the market bottom. One chart includes all of the data, and the second chart excludes the datapoint from the bottom in 1932 because it was such an outlier.

(Click To Enlarge)

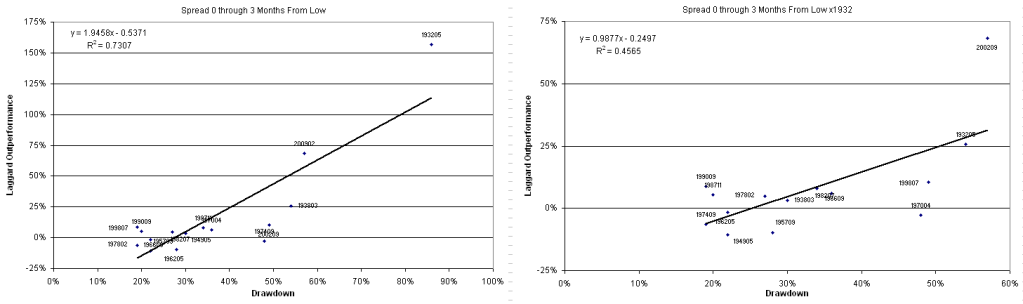

You can see there is a very strong relationship between drawdown and laggard outperformance over the first three months after the market low. Excluding the datapoint from 1932 weakens the fit somewhat, but the relationship is still there. Now compare the performance over the first 3 months to the performance of the next 9 months (months 3-12).

(Click To Enlarge)

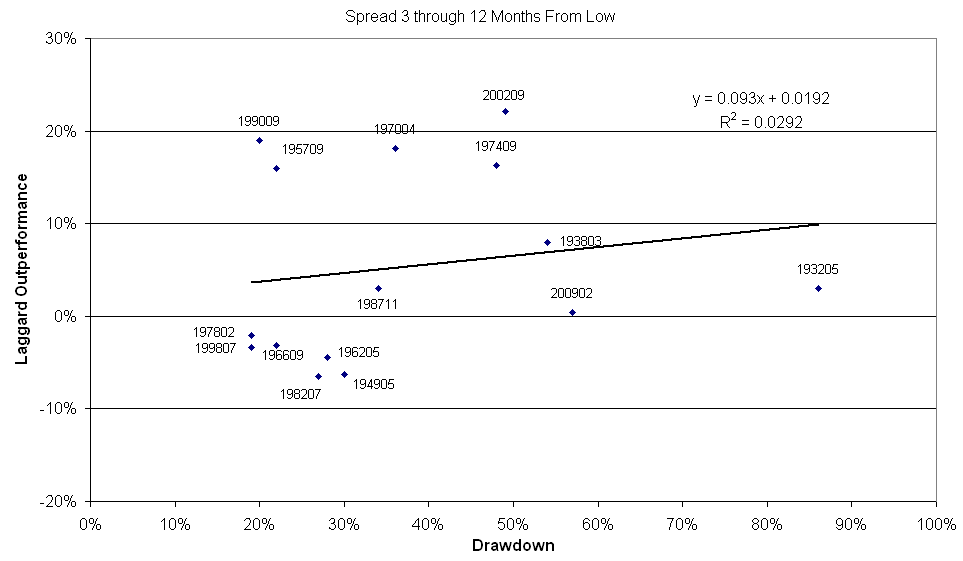

Once you get past the initial thrust off the bottom there is very little correlation between laggard outperformance and drawdown. Sometimes the laggard rally ends, and the leaders begin to outperform again. Other times the laggards continue to outperform. It is very unreliable and you might as well just toss a coin.

In looking at the data, it is my opinion that the reason it is so difficult to consistently capitalize on the laggard rallies is that market timing becomes so important. Most of the consistent money is made in the laggards in the initial thrust off the lows. I think it goes without saying that in order to get in at the lows you either need to be a very good market timer or very lucky! Buying laggards near what you think is the bottom can be a disaster. Many people (yours truly included) thought the market bottomed in November 2008. If you had bought some bank stocks at that point you had problems as they got crushed in the first part of 2009. Bank Of America, one of the poster children for laggard stocks in the decline, went from $11.50 to $3.75 from the November lows until the ultimate lows in March 2009. You would have ultimately been bailed out in that trade if you held on because the laggard rally has been so dramatic. But I think everyone reading this needs to be honest with themselves: very few people would have actually held on to that stock for the entire round trip.

Catching a nice laggard rally requires tremendous timing. It also requires incredible fortitude because you must buy companies that appear to have very dim prospects of survival (let alone outperformance). If you can do these two things you must be extremely nimble because the effect doesn’t appear to be consistently reliable once the initial thrust is done. We have just seen the second largest laggard rally in history (at least according to this data). This laggard rally has been about double what we have seen from the rallies off the lows in 1938, 1990, and 2002. Given the magnitude of outperformace by the laggards it is extremely tempting to attempt to enter into a regime switching methodology to capitalize on it. I see two problems with this. First, over time it has been more difficult to consistently capitalize on this phenomenon than the most recent rally would suggest. Second, this laggard rally has been historically huge. You probably won’t get the same results going forward for quite some time. Of course there will be laggard rallies in the future, but history shows they have a higher probability of being much more muted than the current one.

Posted by: John Lewis

A New Misery Index

December 15, 2009Back in the 1970s, economist Arthur Okun coined the term “misery index” for a measurement that combined the inflation rate and the unemployment rate. The thought was that everyone in the country would be feeling miserable about the economy if both of those rates were high.

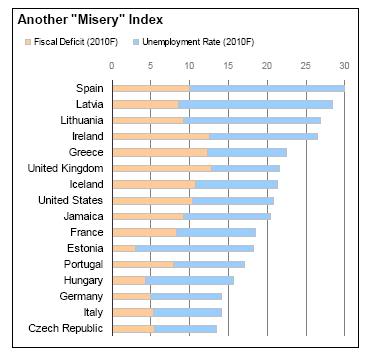

Recently, Moody’s put out their 2010 sovereign outlook. They incorporated a slightly different misery index for sovereign borrowers that incorporates the fiscal deficit and the unemployment rate. The Financial Times has a summary here, along with the table that I have reproduced below.

Here’s what I find interesting about the chart: most of the countries that are in the worst shape are relatively developed economies. The U.S. and western Europe feature in a lot of the top spots. Many of the entrants on the list are wealthy countries that have spent themselves into a problem.

I would not have guessed that the table would look the way it does. We see the same thing all of the time in our Systematic Relative strength accounts where we find ourselves buying stocks or asset classes that would not necessarily have occurred to us to buy in the absence of a systematic approach. It’s a pretty clear reason to use quantitative data and not hunches, emotion, or guesswork to determine where to invest. It’s also a pretty clear reason to keep emerging markets and other non-traditional asset classes on your radar. When you examine everything from a quantitative framework, sometimes it is surprising what pops out.

Posted by: Mike Moody

Passionate About Our Dispassion

December 15, 2009(Click to Enlarge)

Source: Bespoke Investment Group

The Dow Jones Industrial Average has gained 32% since President Obama took office, on pace to be the second best first year of a US President since 1900. Despite the fact that, according to Rasmussen, only 26% of the nation’s voters strongly approve of the way that Barack Obama is performing his job as President (41% of voters strongly disapprove) the stock market is going up.

It is often a mistake to try to out think the market or to allow political views to dictate investment strategy. This is just another reason that we favor managing money using dispassionate relative strength models.

Posted by: Andy Hyer

Data Obsession

December 15, 2009Wow. We thought we were data geeks… Wired Science reports that some parents are taking baby development tracking to the extreme.

With the help of the Trixie Tracker website, they know they’ve changed exactly 7,367 diapers for their three-year-old son and 969 for their three-month-old daughter. They also have a graph of precisely how many minutes each of their children slept on nearly every day since birth. During their daughter’s first month, the data shows she averaged 15 hours of sleep a day, which is two hours more than her brother at the same age and well above average for other Trixie Tracker babies.

Posted by: Andy Hyer

The Bond Vigilantes Ride Again

December 14, 2009In the 1980s, investment strategist Stanley Salvigsen coined the term “bond vigilantes” to describe the sometimes harsh oversight function that bond market investors provide sovereign governments. If a government’s monetary or fiscal policy got out of control, the vigilantes were there to string them up in a hurry—typically by reducing purchase demand enough to drive up interest rates. Interest rates have been in a long secular decline since the early 1980s, so the bond vigilantes haven’t been seen for quite some time. One might be forgiven for thinking they had galloped off to another movie set.

Events in Europe last week showed clearly that the bond vigilantes are still on patrol. Investors were none too happy with the balance sheets of Greece and the U.K., and both countries were socked with an increase in interest rates on their sovereign debt. Indeed, although central banks like to believe that they have control of short-term interest rates, ultimately it is the market—through supply and demand-that controls the rate at which governments must borrow.

Although our national balance sheet is not quite as strained as that of Greece, the U.S. will not be immune from the bond vigilantes. In fact, they’ve already made their presence felt by punishing the dollar when the current account deficit got out of control. I noticed that the recent report from the Commission on Budget Reform has lots of suggestions for reducing the deficit, but doesn’t want them to take effect until 2012. Let’s hope that it is not too late to head the bond vigilantes off at the pass.

Posted by: Mike Moody

Right on Schedule

December 14, 2009The Commission on Bedget Reform has come up with a proposal to shrink the Federal deficit. This article from the Wall Street Journal gives some of the highlights. Of course, there’s a catch:

They recommend waiting until 2012 to implement policy changes to avoid harming their re-election prospects the economic recovery.

The strike-through is mine, obviously. But the economic recovery is a pretty good cover story.

In other words, balance the budget-just not now.

Posted by: Mike Moody

Weekly RS Recap

December 14, 2009The table below shows the performance of a universe of mid and large cap U.S. equities, broken down by relative strength decile and quartile and then compared to the universe return. Those at the top of the ranks are those stocks which have the best intermediate-term relative strength. Relative strength strategies buy securities that have strong intermediate-term relative strength and hold them as long as they remain strong.

Last week’s performance (12/7/09 – 12/11/09) is as follows:

Relative strength laggards saw slightly better performance than relative strength leaders last week.

The chart below is the spread between the relative strength leaders and relative strength laggards of the same investment universe (U.S. mid and large cap stocks.) When the chart is rising, relative strength leaders are performing better than relative strength laggards.

(Click to Enlarge)

The laggard rally from the March 9th lows seems to have transitioned into a period that is currently favoring the relative strength leaders and relative strength laggards equally.

Posted by: Andy Hyer

The Verdict on Morningstar

December 11, 2009Advisor Perspectives recently completed a study on the usefulness of Morningstar ratings over the course of a full market cycle. The question at hand is basically whether the Morningstar star ratings are useful in predicting future performance. The study’s finding was unambiguous:

Our analysis found that Morningstar’s ratings lost virtually all of their predictive ability when measured over a full market cycle.

In other words, despite the retail investor’s desire to use the star ratings to help select mutual funds—not to mention the fund companies’ desire to use the rating in advertising—they don’t help. You could select funds with a coin flip and it would be just as helpful. (The article includes enough data to make your head spin.)

I suppose this is good news and bad news. The bad news is that there is no shortcut in due diligence. You need to spend time understanding the investment strategy and the reasons behind the performance, whatever it is. The good news is that there is no shortcut in due diligence. Clients can’t simply look at a star rating and reliably predict future performance. They are going to need the help of skilled advisors who are willing to dig in and do the work.

Bottom line: Ignore the star rating and spend your time understanding the investment strategy.

Posted by: Mike Moody

Mohamed El-Erian: Two Issues For Investors

December 11, 2009Fortune editor Geoff Colvin has a great interview with Pimco giant Mohamed El-Erian. Among other things, Mr. Colvin asks him what investors will have to do differently going forward to cope with the new environment. Mr. El-Erian’s response is quite direct:

The average investor has two issues today. First, the average investor is too U.S.-centric. There’s a reason for that; the behavioral finance people will tell you that we like the familiar, so we tend to invest in names that we know, that give us comfort.

The problem is that you don’t want to be too U.S.-centric in a globalizing world where the center of gravity is shifting. So the first thing for the average investor to recognize is that the asset allocation of tomorrow is much more global than the asset allocation of yesterday.

Second, most of us have been very lucky — we haven’t had to worry about inflation for a long time. We’re moving toward a much more fluid world in which, at some point, inflation will come back.

Getting more global is what our Systematic RS Global Macro account is all about. In addition, Mr. El-Erian suggests that the individual needs access to alternative assets, specifically an inflation hedge. Global Macro covers the waterfront here too, with baskets for assets from inflation-protected bonds, to precious metals, basic materials, energy, and other commodities, to real estate and foreign currencies. All of these asset classes have typically been available in the past only to qualified investors through a limited partnership format that also has leverage, high fees, and a lockup period. Global Macro is available as a separate account and through the Arrow DWA Tactical Fund (DWTFX)-no leverage, standard fees, and no lockup.

Most important, the Global Macro portfolio comes along with a systematic method for determining when and how much exposure to take in various asset classes as conditions change. It might be just what’s needed in the new world order.

Click here to visit ArrowFunds.com for a prospectus & disclosures. Click here for disclosures from Dorsey Wright Money Management.

Posted by: Mike Moody

Essence of Relative Strength

December 11, 2009“I can’t change the direction of the wind, but I can adjust my sails to always reach my destination.” - Jimmy Dean

Posted by: Andy Hyer

Household Savings

December 10, 2009American households, it seems, have finally gotten the message that too much debt is a problem. Here are some great graphics from The Atlantic that show how households have gone to a net savings position.

Maybe someday our legislators will be inspired by their example.

Posted by: Mike Moody

The Ongoing Consumer Spending Boom

December 10, 2009If the world economy gets pulled out of recession, it will likely be from consumer spending. The U.S. economy is the largest in the world and consumer spending accounts for approximately 2/3 of our economic activity. A reviving U.S. consumer will be a big help not just domestically but globally.

The U.S., however, is not in the midst of a consumer spending boom and the prospect for one does not seem to be on the horizon either. The ongoing consumer spending boom that I am referring to is going on in China. This year, China expects to overtake the U.S. in auto sales, refrigerators, washing machines, and desktop computers. The biggest consumer market in the world in a few years may no longer be the U.S.—it will be China.

The “new normal” that Bill Gross likes to talk about is going to be a global investment marketplace, not one that is focused on the U.S. only. Globalization already has all kinds of problems and the increasing pace of globalization will create even more issues that investors will have to deal with. It may not be comfortable to move toward a global investment policy, but it might be the only way to earn a decent return.

Posted by: Mike Moody

Investors’ 2010 Forecast

December 10, 2009CNN Money is currently running an informal poll on their website. They are asking investors ”Which type of investments will you focus on in 2010?”

The results so far are:

U. S. Stocks 35%

Emerging Markets 15%

Bonds 10%

Commodities 6%

Bank accounts 33%

The portfolio, you may note, is cash-heavy and U.S.-centric. Instead of getting bogged down in a possibly outmoded policy portfolio, why not select “all of the above?” With the exception of bank accounts, all of these asset classes are also choices available in our Systematic Global Macro portfolio. (The Global Macro strategy is available both as a separate accounts and a mutual fund.) Instead of bank accounts, Global Macro substitutes short-term U.S. government bonds—but it also covers a much broader range of asset classes, including domestic and international equities, fixed income, inverse funds, commodities, currencies, and real estate. Rather than guessing what may work in 2010, it might be more prudent to use a disciplined and rigorously tested method to select investments.

Posted by: Harold Parker

The Municipal Debt Bomb

December 10, 2009Municipal bonds are heavily owned by individual investors because of the income tax exemption and they are widely considered to have safety characteristics second only to U.S. Treasury debt. Money has been pouring into bond funds this year, a fair amount of it into municipal bond funds.

Be careful: the credit characteristics of this market are not what they used to be. According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, “over the past decade, municipal debt has doubled, to nearly $2.93 trillion.” Yes, that’s trillion with a T. The article goes on to note that

Over all, state and local governments’ total liabilities—including loans and accounts payable as well as bonds—exceeded their assets by $319.3 billion at the end of the second quarter, the Fed said in its quarterly Flow of Funds publication.

That can’t be good. When your liabilities exceed your assets, you’ve got a big problem. Of course, governments can raise taxes to cover the debt service, but right now that’s like trying to get blood from a stone. Continuing high unemployment is going to make it difficult to convince the electorate that they need to pay more taxes. Additionally, voters are not happy about the continuing ramp-up in local government spending. Since many local governments cannot balance their budgets, they are borrowing even more money to cover the gap. In 2009, muni bond issuance topped $400 billion for only the third time ever ($493 billion), and even more issuance—$560 billion—is expected for 2010. In other words, the hole is already deep and local governments are still digging.

Taxable U.S. investor portfolios are still often cast in the 60% blue chips/40% muni bonds mold. In the past, that has worked pretty well. Maybe it will continue to work in the future, but there’s certainly a possibility that the financial crisis has pushed many muni bond issuers past the tipping point. Portfolios may need to be significantly more flexible and more tactical to navigate the financial markets of the future.

Posted by: Mike Moody

$7 Trillion

December 9, 2009That’s the size of the wall of money held in cash by U.S. households. According to an article on Morningstar:

Data released by the Federal Reserve show that private cash holdings by households and companies as a percentage of nominal US GDP is just shy of 72 per cent, or about $10,120bn, as of the second quarter of 2009. The US household sector currently holds about $7,760bn in liquid assets. These cash balances are higher than the previous peak in the 1980s.

With returns on money market funds still low – the interest paid has barely turned positive – there are plenty of market watchers who expect the money to keep moving out of cash and prop up buying of stocks, corporate bonds and other assets with higher returns.

“The last time we had a big money mountain was in the 1980s,” says James Paulsen, chief investment strategist at Wells Capital Management. “For the next 20 years, a little bit more went into economic activity and some went into stocks and bonds. This same pattern will be repeated next year and for a number of years to come.”

There are a couple of interesting features in the current situation. 1) there is a ton of cash on the sidelines, and 2) the return on the cash is virtually nonexistent. Clearly, some of the cash will be looking for a home. Where will that new home be? It’s impossible to predict—but money will generally go where the returns have been. Relative strength is just a systematic way to measure where the best returns have been. Often it turns out that those trends continue for some time. The wall of money has created some potential investment opportunities and a systematic application of relative strength is one useful way to hone in on them.

Posted by: Mike Moody

Auto Sales Up 98%

December 9, 2009in China. And up 68% year over year in India. Phenomenal. And they apparently did not need a cash-for-clunkers program to do it. Rapid economic growth is occurring—just not in the United States or Europe.

Rapid growth in auto sales will have potential pricing consequences in world markets in oil and steel, and in local markets for aftermarket auto parts, and so on. As auto dealers and their employees do well, there may be a general trickle-down effect in consumer goods throughout their domestic economies. In other words, revenues create investment opportunities.

The U.S. market is going to continue to be important, but it’s a mistake to overlook opportunities elsewhere around the globe. To me, headlines like this are a primary reason to expand your investment horizons globally.

Posted by: Mike Moody

Black Swan Of Laggard Rallies

December 9, 2009It has been a difficult year for Relative Strength strategies. RS is a “success-based” factor, and what has worked this year has been companies that have had little success. From an RS standpoint, the laggards (those stocks that declined the most heading into the market low) have outperformed the leaders (those that held up the best in the market decline) by a historically wide margin. According to research by The Leuthold Group in their December 2009 Green Book, this year has been the second best year for laggard outperformance in history. The best year for the laggards to outperform the leaders was all the way back beginning at the market low in June 1932. Their study uses Ken French’s data, and calculates the performance spread between the leaders and laggards in the first 12 months of a new bull market.

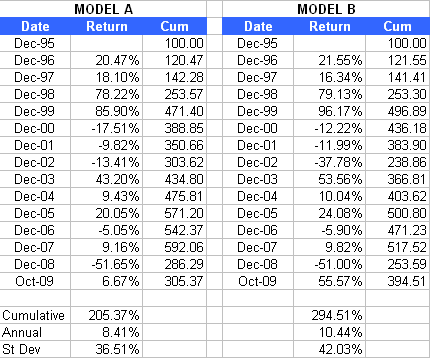

The historically high laggard outperformance presents interesting challenges for anyone who is testing and systematically applying an RS factor. Take the following two models, for example:

For purposes of this post the actual model specifications don’t matter. But for those of you who will e-mail me anyway, Model A is a simple 12-month trailing return model with 50 holdings. Very straightforward and plain vanilla. Model B is just a test I was playing around with that attempts to adapt more quickly to the market. In effect, the RS factor is a 12-month trailing return unless there is a 20% swing in the S&P 500. If there is a 20% swing, the lookback period changes from 12 months ago to the market high or low where the swing is measured from.

If you just look at the cumulative return you would say that Model B is much better. But is it really? There are some big differences in the performance of the two models in 2002 and 2003, but look at the difference in 2009. Essentially, all of the outperformance from Model B comes in 2009. In fact, if you ran these two models as of 12/31/2008 you would have said that Model A is better (+186% for Model A versus +154% for Model B).

You can’t simply look at the return streams of any model in a vacuum. There are reasons why the returns are what they are, and those reasons need to be considered. I think hitching your wagon to an RS strategy that makes a huge percentage of its relative (to other models) gains in a year like 2009 is asking for trouble. According to Leuthold’s research, the next set of laggard rallies that were difficult for RS were off the market lows in 1990, 2002, and 1938. All three of those instances were around 40% outperformance by the laggards over 12 months. This current laggard rally is almost 2 times that (77%).

Could it be that we have just seen the proverbial Black Swan of laggard rallies? It’s certainly possible. While a laggard rally of this magnitude can certainly happen again (and probably will at some point), the data suggests that relying on this type of rally to generate returns using an RS model over long periods of time is not wise. So like most things that get tested, I would say the idea of Model B was very interesting, but will wind up in the graveyard of good ideas.

Posted by: John Lewis

Bubble Prognostication

December 9, 2009Identifying bubbles seems to be a preoccupation of more and more market participants these days. Talk about bubbles in treasuries and gold seem to be everywhere currently. They will likely be right at some point. However, it does seem that many people were shunning real estate because of the threat of a bubble years before it actually peaked. It is easy to see why there is so much fascination with trying to time bubbles. After all, think of all the money you would have if you could get in at the low and get out at the top ! Never having to worry about the aftermath of bubbles would make investing so…idyllic.

There are certain aspects of bubbles that are predictable. Namely, one can predict with a very high degree of confidence that we are going to see numerous bubbles in the future, just like there have been in the past. A bubble timer may correctly identify different phases of every bubble (Stealth Phase, Awareness Phase, Mania Phase, and finally Blow Off Phase.) However, the challenge is that every bubble is just different enough to make timing them practically impossible.

For example, you may remember the story of hedge fund manager Julian Robertson who in the 1990s very correctly and loudly pointed out the Dot.com bubble. As a result of his conviction that the technology bubble was going to burst, he refused to participate in technology in the late ’90s and his hedge fund, Tiger Management, lost 4% in 1998, and lost 19% in 1999. Tiger Management closed down in February of 2000, just before the bubble burst. He was absolutely right on the fundamental story, but the timing was off.

Capitalizing on bubbles is a major reason that relative strength strategies have the potential to deliver superior results over time. However, instead of trying to identify tops in bubbles we simply allow the market forces to dictate when we exit a trade. Invariably, we will exit the trade after the trend has declined from its peak and we will have given back some of what was gained in the often multi-year run-up to the peak. However, it is better to make money than getting caught up focusing on how the market should perform based on your fundamental position, no matter how correct that fundamental position is.

Posted by: Andy Hyer

Good Odds for 2010

December 9, 2009Now that it has been nine months since the bear market low, you may be wondering how much longer this bull market can go. It is important to note that there is strong historical precedent for bull markets to follow through in year two.

Sam Stovall, S&P’s chief investment strategist, recently pointed out that all but one of the 14 previous bull markets since 1932 survived into a second year. They then averaged 12.5 percent gains during that year (AP, 12/08/09).

Good reason to be optimistic.

Posted by: Andy Hyer

Why Closet Indexers Abound

December 8, 2009The Wall Street Journal had an excellent article today about fees and active management. The article pointed out that many funds, although they are charging typical fees for active management, are actually indexed quite closely to their benchmark. In essence, the investor is getting a very expensive index fund.

Why is this practice so common—and, according to the article, still a growing tendency in the fund management business? A few reasons are mentioned, but the one that struck a chord with me was the following:

Since a manager’s performance is usually judged relative to an index, staying close to the benchmark can be a way of playing it safe, says Graham Spiers, chief investment officer at wealth manager Waypoint Advisors, Norfolk, Va. “There is a framework where if managers make a mistake or are wrong, they can lose their jobs,” says Mr. Spiers, who worked at asset-management firms for 10 years.

Managers who take more risks often have periods when they lag behind the benchmark, forcing them to preach patience and point to their long-term records as a reason for investors and employers not to lose faith. That can be harder than staying close to an index and delivering returns that don’t stand out, either positively or negatively, Mr. Spiers says.

The bold is mine. I emphasize it because the business issue in fund management is retaining assets. Clients are often extremely concerned when a manager’s results vary from the benchmark. I know that we spend the bulk of our conference call time with clients discussing this very issue during periods of underperformance. It is well-known in the money management industry that clients, in general, have itchy trigger fingers. DALBAR data shows that the average mutual fund holding period is only about three years, not nearly long enough to make sure that results are meaningful. So a lot of firms, I suspect, make a business decision. They figure that if they stay close to the benchmark that they will retain clients longer, and they are willing to give up the chance of significant outperformance over time to do it. You can call it cynical or you can call it realistic.

There’s an important tradeoff that clients don’t often consider. If you are hugging the index, how are you going to outperform it? The only way to outperform a benchmark over time is to deviate from the benchmark-in the positive direction-over the course of a market cycle. So you have your choice: a truly active fund with all that it entails, or an expensive index fund.

We’ve made the decision to run portfolios with very high active share. Our Systematic Relative Strength portfolios are a lot different than the benchmark. We recognize that 1) we will be stuck preaching patience at certain points in the market cycle and 2) our investors and their advisors will have to be much more sophisticated and patient than the average client. On the other hand, there is the prospect of doing significant good for the client’s net worth over time.

Posted by: Mike Moody