The Journal of Indexes has the entire current issue devoted to articles on this topic, along with the best magazine cover ever. (Since it is, after all, the Journal of Indexes, you can probably guess how they came out on the active versus passive debate!)

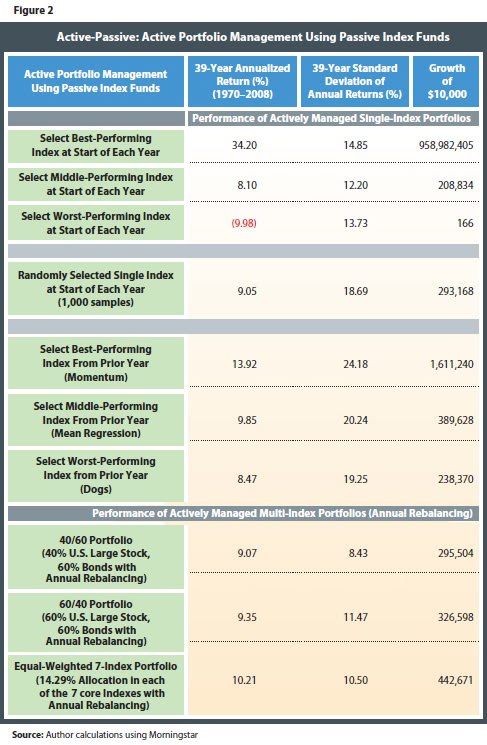

One article by Craig Israelson, a finance professor at Brigham Young University, stood out. He discussed what he called “actively passive” portfolios, where a number of passive indexes are managed in an active way. (Both of the mutual funds that we sub-advise and our Global Macro separate account are essentially done this way, as we are using ETFs as the investment vehicles.) With a mix of seven asset classes, he looks at a variety of scenarios for being actively passive: perfectly good timing, perfectly poor timing, average timing, random timing, momentum, mean reversion, buying laggards, and annual rebalancing with various portfolio blends. I’ve clipped one of the tables from the paper below so that you can see the various outcomes:

Click to enlarge

Although there is only a slight mention of it in the article, the momentum portfolio (you would know it as relative strength) swamps everything but perfect market timing, with a terminal value more than 3X the next best strategy. Obviously, when it is well-executed, a relative strength strategy can add a lot of return. (The rebalancing also seemed to help a little bit over time and reduced the volatility.) Maybe for Joe Retail Investor, who can’t control his emotions and/or his impulsive trading, asset allocation and rebalancing is the way to go, but if you have any kind of reasonable systematic process and you are after returns, the data show pretty clearly that relative strength should be the preferred strategy.

I always get annoyed when these types of comparisons use “straw man” momentum portfolios! Seriously, 12 month momo held for 12 months is pretty far from optimal ….

I guess they HAVE to do this, though, because if they took a good, hard look at something more optimal, they would experience such cognitive dissonance that they’d have to abandon their passivity …

While the absolute return in higher for momo, notice the Sharpe ratio would be lower. The returns would be great if you could weather the volatility; most DIY’s cannot. In a sideways to declining market, the lower Sharpe ratio strategy would be on the sidelines, most likely as a risk management tool. This is also assuming the “straw man” strategy with no further input.

Ah, the “Cult of Sharpe!” It’s dangerous to your long-term wealth growth …

Best Sharpe ratio a DIYer could ever get is by investing in 1-year T-Bills. That strategy also gives them best chance possible of having each particular year of returns outpace their CPI-based COLAs. But is it a good idea to maximize Sharpe?

This might be a good post for the blog here, I think …

Like I said in the article, if you can’t control your emotions and/or impulsivity, maybe you should just rebalance and take a lower return. But if you are after returns-and obviously the cost of those returns, like the cost of all returns, is volatility-then it makes sense to use relative strength. Here’s an experiment: ask your client if they would prefer a $326,000 retirement portfolio (60/40 blend) or a $1.6 million retirement portfolio (momentum) that came with twice as much volatility.

The evidence shows that most DIY’s cannot take even the volatility of a 60/40 blend. Dalbar’s holding periods even for those type of funds are barely three years. Clients need to be better mentally prepared for equity volatility generally.

Hey Bill, no cult, just making an observation. Just another item near the bottom of a checklist. Everything else looks fine, am I being compensated for the risk? Yes, great. No, am I ok with that or are there other options.