No, this is not a post on personality disorders.

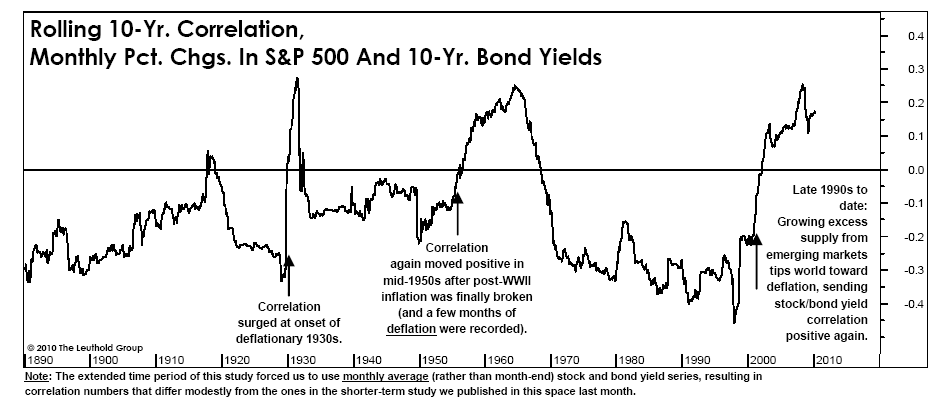

Rather, it is a post on the inherently unstable nature of correlations between securities and between asset classes. This is important because the success of many of the approaches to portfolio management make the erroneous assumption that correlations are fairly stable over time. I was reminded just how false this belief is while reading The Leuthold Group‘s April Green Book in which they highlighted the rolling 10-year correlations in monthly percentage changes between the S&P; 500 and the 10-year bond yield. Does this look stable to you? Chart is shown by permission from The Leuthold Group.

(Click to Enlarge)

If you are trying to use this data, would you conclude that higher bond yields are good for the stock market or bad? The answer is that the correlations are all over the map. In 2006, William J. Coaker II published The Volatility of Correlations in the FPA Journal. That paper details the changes in correlations between 15 different asset classes and the S&P; 500 over a 34-year time horizon. To give you a flavor for his conclusions, he pointed out that Real Estate’s rolling 5-year correlations to the S&P; 500 ranged from 0.17 to 0.75, and for Natural Resources the range was -0.34 to 0.49. History is conclusive – correlations are unstable.

This becomes a big problem for strategic asset allocation models that use historical data to calculate an average correlation between securities or asset classes over time. Those models use that stationary correlation as one of the key inputs into determining how the model should currently be allocated. That may well be of no help to you over the next five to ten years. Unstable correlations are also a major problem for “financial engineers” who use their impressive physics and computer programming abilities to identify historical relationships between securities. They may find patterns in the historical data that lead them to seek to exploit those same patterns in the future (i.e. LTCM in the 1990’s.) The problem is that the future is under no obligation to behave like the past.

Many of the quants are smart enough to recognize that unstable correlations are a major problem. The solution, which I have heard from several well-known quants, is to constantly be willing to reexamine your assumptions and to change the model on an ongoing basis. That logic may sound intelligent, but the reality is that many, if not most, of these quants will end up chasing their tail. Ultimately, they end up in the forecasting game. These quants are rightly worried about when their current model is going to blow up.

Relative strength relies on a different premise. The only historical pattern that must hold true for relative strength to be effective in the future is for long-term trends to exist. That is it. Real estate (insert any other asset class) and commodities (insert any other asset class) can be positively or negatively correlated in the future and relative strength models can do just fine either way. Relative strength models make zero assumptions about what the future should look like. Again, the only assumption that we make is that there will be longer-term trends in the future to capitalize on. Relative strength keeps the portfolio fresh with those securities that have been strong relative performers. It makes no assumptions about the length of time that a given security will remain in the portfolio. Sure, there will be choppy periods here and there where relative strength models do poorly, but there is no need (and it is counterproductive) to constantly tweak the model.

Ultimately, the difference between an adaptive relative strength model and most quant models is as different as a mule is from a horse. Both have four legs, but they are very different animals. One has a high probability of being an excellent performer in the future, while the other’s performance is a big unknown.