Emotions are the well-documented cause of most problems in investing. For some reason, it is very difficult for most people to be rational during uptrends, downtrends, or during periods of high volatility-in other words, 90% of the time.

The recent “flash crash,” besides spawning humorous t-shirts, got investors riled up again.

The clever t-shirt took me back to 1987 when it was de rigeur for advisors to own at least one piece of ”I Survived the Crash” apparel. I thought about a great, great Joe Nocera column in the New York Times as the 20th anniversary of the 1987 stock market crash was looming. He was interviewing Jason Zweig, who had a priceless anecdote about the father of modern portfolio theory, Harry Markowitz.

“There is a story in the book about Harry Markowitz,” Mr. Zweig said the other day. He was referring to Harry M. Markowitz, the renowned economist who shared a Nobel for helping found modern portfolio theory — and proving the importance of diversification. It’s a story that says everything about how most of us act when it comes to investing. Mr. Markowitz was then working at the RAND Corporation and trying to figure out how to allocate his retirement account. He knew what he should do: “I should have computed the historical co-variances of the asset classes and drawn an efficient frontier.” (That’s efficient-market talk for draining as much risk as possible out of his portfolio.)

But, he said, “I visualized my grief if the stock market went way up and I wasn’t in it — or if it went way down and I was completely in it. So I split my contributions 50/50 between stocks and bonds.” As Mr. Zweig notes dryly, Mr. Markowitz had proved “incapable of applying” his breakthrough theory to his own money. Economists in his day believed powerfully in the concept of “economic man”— the theory that people always acted in their own best self-interest. Yet Mr. Markowitz, famous economist though he was, was clearly not an example of economic man.

This story basically says it all. Even the theory’s originator was incapable of applying it, due to his emotional hang-ups!

We think this is the very best argument for our systematic relative strength approach. Relative strength has been shown to work over time and our process is systematic. There will be no emotional backsliding on the part of the computer when it comes to calculating our relative strength ranks. I cannot stress enough how much more important the systematic execution of the process is, as opposed to the individual items that might be held in a portfolio. A recent white paper by one of our portfolio managers, John Lewis, makes this point powerfully by picking portfolios of high relative strength stocks at random.

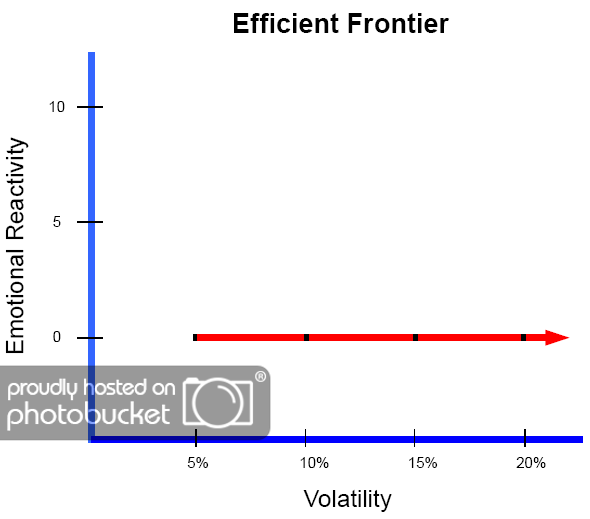

The point is that our Systematic Relative Strength portfolios keep investors continuously exposed to the relative strength return factor, come hell or high water. (There’s plenty of both in financial markets.) Over time, that’s very likely to be a winning strategy. The coordinates for the real efficient frontier are emotional reactivity and volatility, not risk and return. If you can suppress your emotions and stay rational, you have a chance.

Jason Zweig, in Joe Nocera’s article, had a nice quip for that too:

As our interview was winding down, Mr. Zweig told me a story — “I think it might even be true” — about Charles T. Munger, the Los Angeles lawyer best known as Mr. Buffett’s sidekick at Berkshire Hathaway. “A woman was sitting next to him at a dinner party in L.A.,” Mr. Zweig said. “She turned to him and said, `You’re Warren Buffett’s partner, and a great investor. Tell me, what is your secret?’”

Mr. Munger looked up at her. “I’m rational,” he said. Then he went back to his dinner.

Posted by Mike Moody

Posted by Mike Moody