A few months ago I had a post about the Momentum Echo (click here to read the post). I ran across another relative strength (or momentum if you prefer) paper that tests yet another factor. In Seung-Chan Park’s paper, “The Moving Average Ratio and Momentum,” he looks at the ratio between a short-term and long-term moving average of price in order to rank securities by strength. This is different from most of the other academic literature. Most of the other studies use simple point-to-point price returns to rank the securities.

Technicians have used moving averages for years to smooth out price movement. Most of the time we see people using the crossing of a moving average as a signal for trading. Park uses a different method for his signals. Instead of looking at simple crosses, he compares the ratio of one moving average to another. A stock with the 50-day moving average significantly above (below) the 200-day moving average will have a high (low) ranking. Securities with the 50-day moving average very close to the 200-day moving average will wind up in the middle of the pack.

In the paper Park is partial to the 200-day moving average as the longer-term moving average, and he tests a variety of short-term averages ranging from 1 to 50 days. It should come as no surprise that they all work! In fact, they tend to work better than simple price-return based factors. That didn’t come as a huge surprise to us, but only because we have been tracking a similar factor for several years that uses two moving averages. What has always surprised me is how well that factor does when compared to other calculation methods over time.

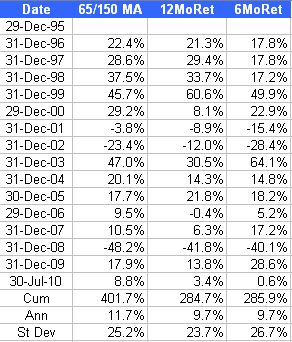

The factor we have been tracking is the moving average ratio of a 65-day moving average to the 150-day moving average. Not exactly the same as what Park tested, but similar enough. I pulled the data we have on this factor to see how it compares to the standard 6- and 12-month price return factors. For this test, the top decile of the ranks is used. Portfolios are formed monthly and rebalanced/reconstituted each month. Everything is run on our database, which is a universe very similar to the S&P 500 + S&P 400.

(click to enlarge)

Our data shows the same thing as Park’s tests. Using a ratio of moving averages is significantly better than just using simple price-return factors. Our tests show the moving average ratio adding about 200 bps per year, which is no small feat! It is also interesting to note we came to the exact same conclusion using different parameters for the moving average, and an entirely different data set. It just goes to show how robust the concept of relative strength is.

For those readers who have read our white papers (available here and here) you may be wondering how this factor performs using our Monte Carlo testing process. I’m not going to publish those results in this post, but I can tell you this moving average factor is consistently near the top of the factors we track and has very reasonable turnover for the returns it generates.

Using a moving average ratio is a very good way to rank securities for a relative strength strategy. Historical data shows it works better than simple price return factors over time. It is also a very robust factor because multiple formulations work, and it works on multiple datasets.