There are lots of reasons to assume that the U.S. will not turn out like Japan after their market peak in 1989. There are vast cultural differences and many significant differences in the economic systems. Most often, when the Japan-U.S. analogy is brought up by bearish commentators, it is quickly dismissed by those who are more bullish. However, one important way in which the U.S. might not be very different from Japan, or anywhere else, is human psychology. Even across cultures, people tend to have similar cognitive biases. What if it turns out that the U.S. really is on the cusp of a Japan-like experience? What might that be like for investors?

The view on the market side is not encouraging. As a recent article in the New York Times points out:

The decline has been painful for the Japanese, with companies and individuals like Masato having lost the equivalent of trillions of dollars in the stock market, which is now just a quarter of its value in 1989, and in real estate, where the average price of a home is the same as it was in 1983. And the future looks even bleaker, as Japan faces the world’s largest government debt — around 200 percent of gross domestic product — a shrinking population and rising rates of poverty and suicide.

Perhaps even more surprising-and concerning-has been the impact of the slow-motion financial crisis on the psychology of the public:

But perhaps the most noticeable impact here has been Japan’s crisis of confidence. Just two decades ago, this was a vibrant nation filled with energy and ambition, proud to the point of arrogance and eager to create a new economic order in Asia based on the yen. Today, those high-flying ambitions have been shelved, replaced by weariness and fear of the future, and an almost stifling air of resignation. Japan seems to have pulled into a shell, content to accept its slow fade from the global stage.

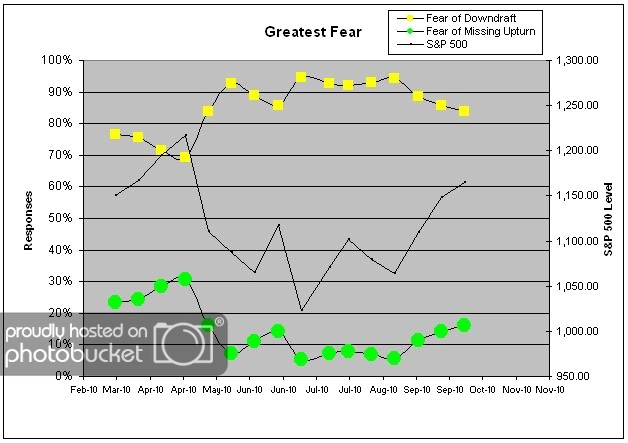

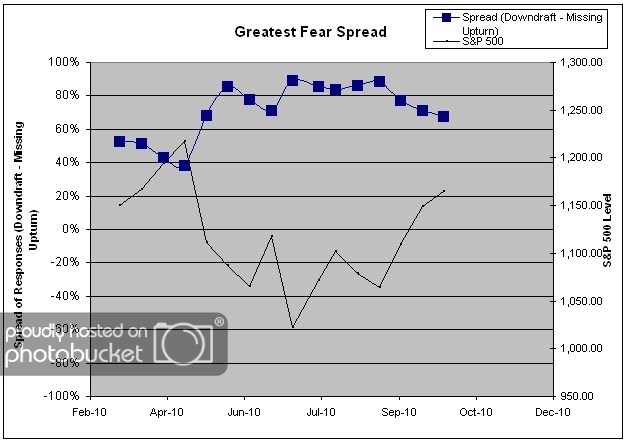

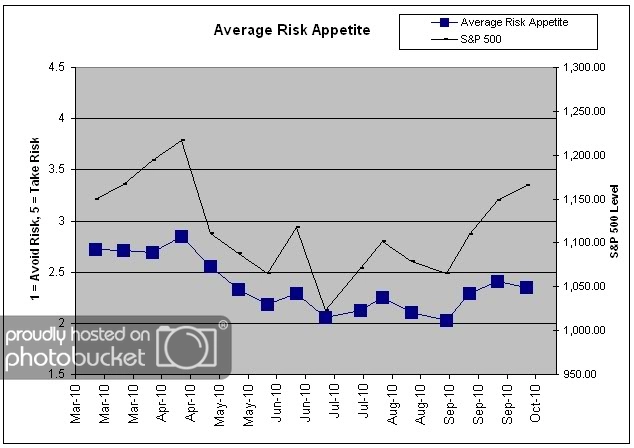

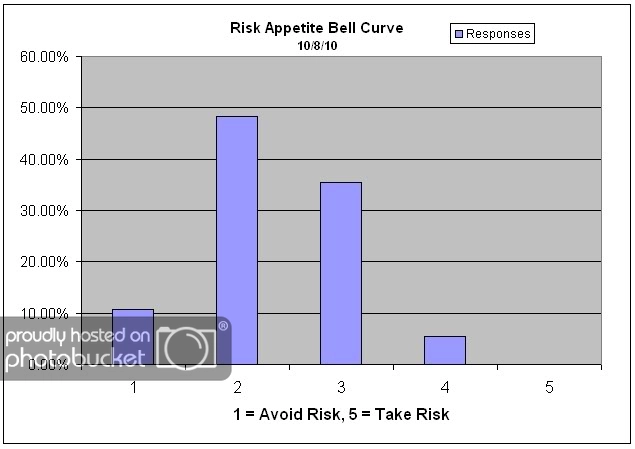

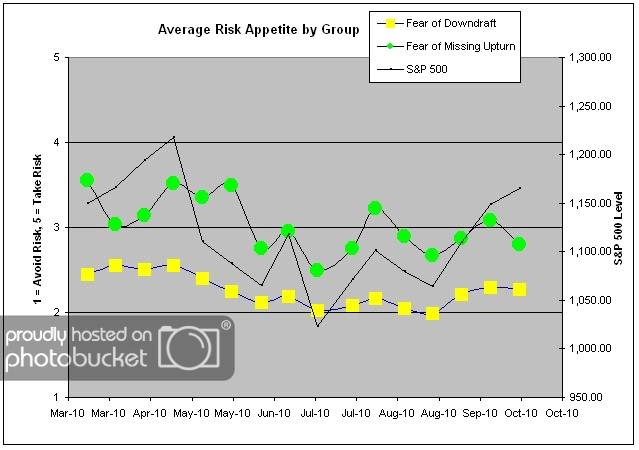

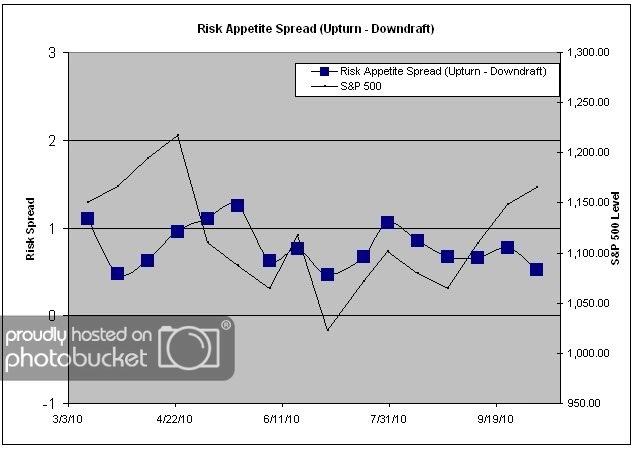

Animal spirits are important. The willingness to take a risk for the prospect of future gain is a requirement for the proper functioning of an entrepreneurial capitalist economy or a strong financial market. Struggling through a difficult economy is one thing, but losing all hope is another thing entirely. When hope disappears, so does the willingness to take risk.

When asked in dozens of interviews about their nation’s decline, Japanese, from policy makers and corporate chieftains to shoppers on the street, repeatedly mention this startling loss of vitality. While Japan suffers from many problems, most prominently the rapid graying of its society, it is this decline of a once wealthy and dynamic nation into a deep social and cultural rut that is perhaps Japan’s most ominous lesson for the world today.

The classic explanation of the evils of deflation is that it makes individuals and businesses less willing to use money, because the rational way to act when prices are falling is to hold onto cash, which gains in value. But in Japan, nearly a generation of deflation has had a much deeper effect, subconsciously coloring how the Japanese view the world. It has bred a deep pessimism about the future and a fear of taking risks that make people instinctively reluctant to spend or invest, driving down demand — and prices — even further.

I think this article is an important read, not so much for the debate about whether the U.S. is economically like Japan or not, but more for the sentiment aspect. Pessimism has economic and financial market consequences. Although I’m concerned about our current national mood, I don’t think Americans have succumbed to permanent pessimism at this point. Given the current low spirits, however, what makes sense from an investment point of view? I think there might be a few right answers.

1) Companies that innovate and grow. Although the broad indexes in Japan are down over the trailing 12 months, a cursory search on the Dorsey, Wright research website reveals many companies with 25%+ returns for that same time frame. Just because the market is dead doesn’t mean every company has thrown in the towel. In many cases, companies in good industries or with new, exciting products will continue to perform well. (In the U.S., Apple would be an apt current example.) Relative strength, incidentally, is a good way to identify strong companies.

2) Global tactical asset allocation. There is usually a bull market somewhere. Lots of countries and asset classes have had phenomenal growth over the last 20 years while Japan has been stagnating. A global approach allows an investor to commit to areas where animal spirits are still powerful, wherever they may be. Maybe Japan has suffered a loss of confidence, but perhaps Brazil is just starting on the way up. There could also be opportunities in alternative asset classes like commodities and currencies. Having a wide-angle view of global business and politics might be very helpful. Here, too, relative strength can be an excellent guide.

If the “PIMCO New Normal” turns out to be the case, then perhaps sovereigns of lightly-indebted nations and canned goods will be the way to go. In a New Normal scenario, a traditional value buyer may end up with a higher-than-normal percentage of value traps-assets that are persistently cheap for a good reason, one that becomes apparent only after you’ve saddled the dog. There’s no telling how events will unfold, but keeping a global perspective and an eye on the mood of the citizenry may prove important.

Posted by Mike Moody

Posted by Mike Moody