This isn’t exactly the topic of my post, but it’s an inquiry along those lines, and it probably got your attention. My occasion for thinking about this was a comment in the Prudent Speculator newsletter, published by Al Frank Asset Management through Forbes. John Buckingham is the chief investment officer, one of the most respected deep value investors around, and has the track record to prove it. In addition, he is a super nice guy and a friend of mine. John cited data from the Ibbotson Yearbook, compiled by Eugene Fama and Ken French, that indicated that value stocks had higher returns than growth stocks:

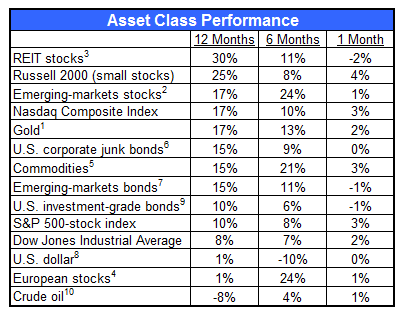

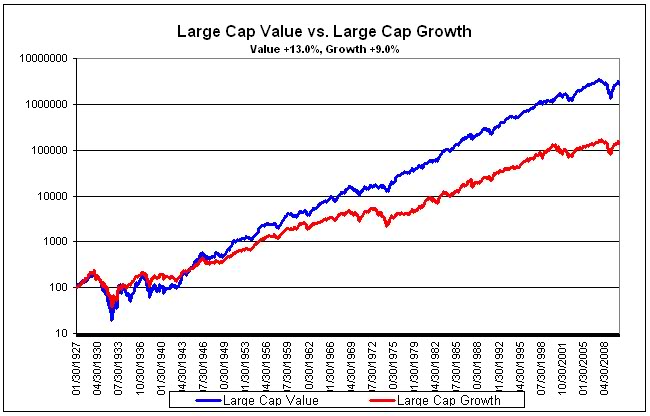

Certainly there have been periods (the 30s and 90s) during which value stocks have lagged growth, but data compiled by Eugene Fama and Ken French show that from 1928-2009, large value stocks had an 11.0% geometric return, compared to 8.7% for large growth, while small value stocks have outperformed by a wider margin (13.9% to 9.0%).

It is untrue that value outperforms growth, contradicted by both experience and statistics, but it is a popular misconception. The misconception stems from the way in which value and growth are defined. The Ibbotson Yearbook in question uses the book-to-market ratio as their metric. This is probably the most common definition in the academic literature as well. Value is virtuously defined as having high book-to-market values. Growth is defined in opposition as those stocks with low book-to-market values. In other words, growth is defined rather perversely as bad value! If growth is defined as bad value, it’s not too surprising that bad value performs worse than good value!

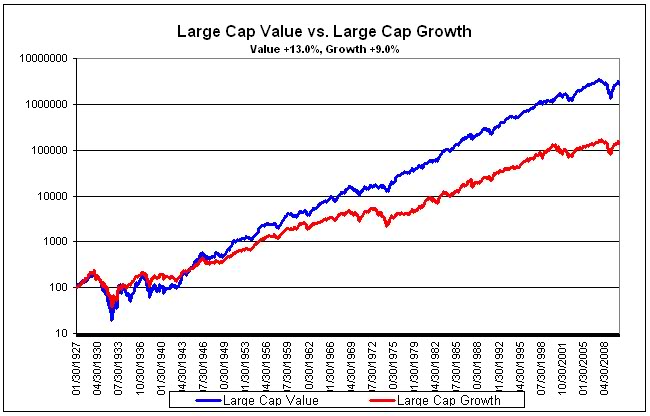

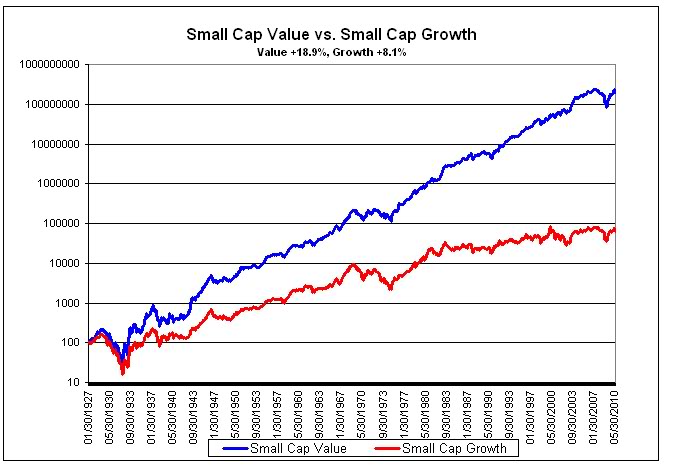

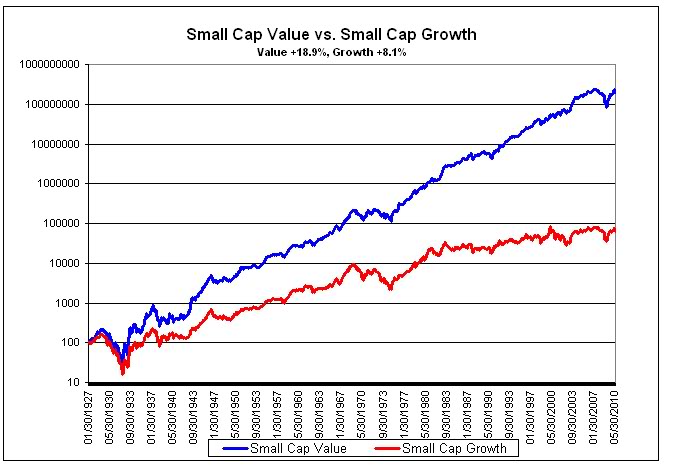

Our research assistant, J.P. Lee, went to the Ken French data library and looked at portfolios formed by market capitalization and book value. The relationships are just as Ibbotson reported, although the numbers are slightly different because of different time periods and a slightly different methodology. For the period from 1/30/1927 to 6/30/2010, large cap value (high book-to-market) stocks had a 13.0% compounded return, compared to 9.0% for large growth (low book-to-market/bad value). Small value stocks outperformed by a wider margin (18.9% to 8.1%). The charts below show the relationships. (Click all charts to enlarge)

source: Ken French Data Library

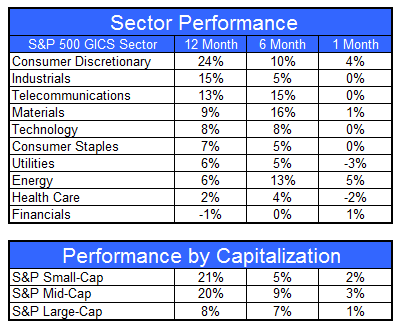

Of course, growth investors don’t actually busy themselves trying to find overpriced stocks! John Brush has written a very important paper about this, Value and Growth, Theory and Practice, (archived on our website) which was published in 2007 in The Journal of Portfolio Management. He points out that all the conventional academic definition shows is that good value beats bad value. He proposes, instead, a list of ten selection factors to define the value and growth styles.

| VALUE FACTORS |

GROWTH FACTORS |

| |

|

| Dividend-to-price |

Short-term change in earnings-to-price |

| Earnings-to-price |

Long-term change in earnings-to-price |

| Cash flow-to-price |

Estimate revisions |

| Expected future earnings-to-price |

Earnings surprise |

| Book value-to-price |

Price momentum |

source: John Brush, Journal of Portfolio Management

Note that the value factors are static, while the growth factors are dynamic. As Brush puts it:

Most value managers will agree that the static factors describe their style. Most growth managers will perhaps more reluctantly recognize the dynamic measures as the basis of their style.

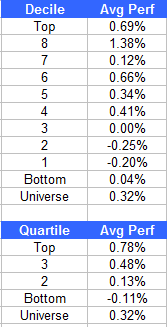

Brush shows that annualized excess returns for un-rebalanced portfolios formed monthly for the period from 1971-2004 are higher for growth stocks over holding periods up to a year, then shift slightly in favor of value stocks for longer holding periods. Of course, in real life, portfolios are not left unchanged for years at a time. Evidence from actual mutual fund portfolios shows that growth stock returns are very similar to value stock returns, if not slightly ahead. For example, John Bogle of Vanguard fame, in his 2003 book, Common Sense on Mutual Funds, writes:

In recent years, the conventional wisdom has been to give the value philosophy accolades for superiority over the growth philosophy. Perhaps this belief predominates because so few observers have examined the full historical record…For the full 60-year period, the compound total returns were: growth, 11.7 percent; value, 11.5 percent - a tiny difference.

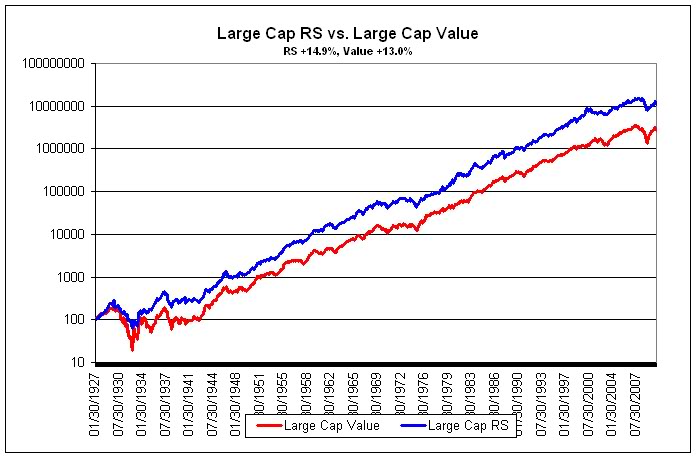

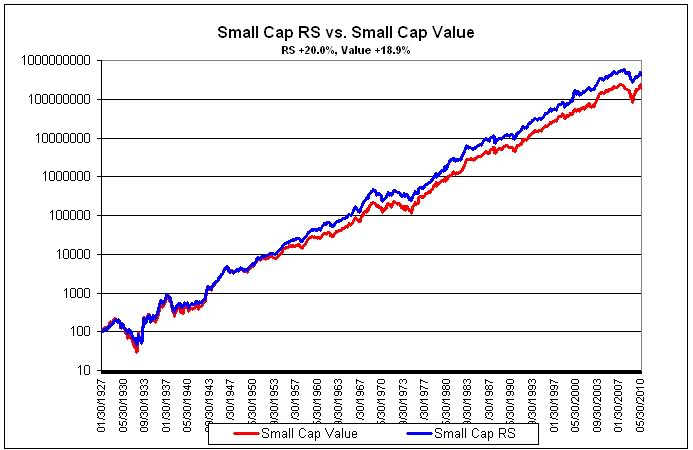

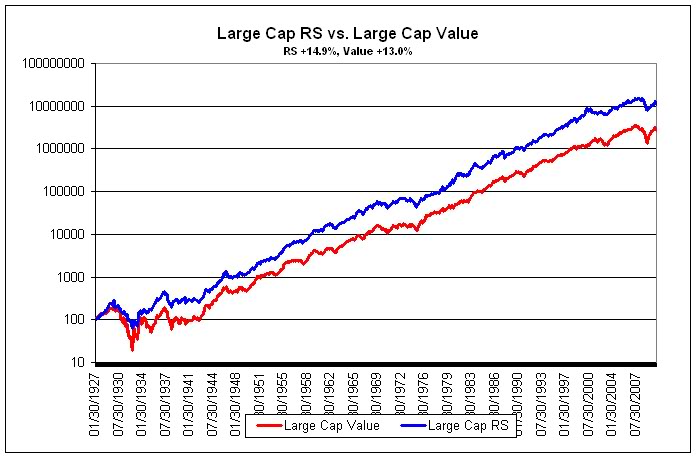

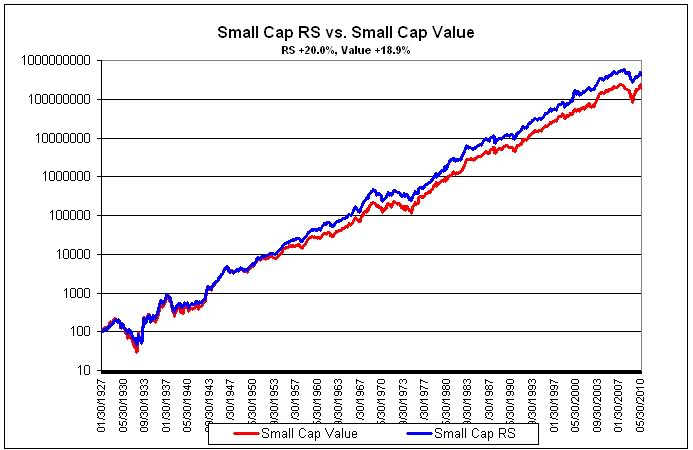

Relative strength is a growth factor. Academics refer to it as price momentum, which is how you will find it listed in the table above. We think it is the most powerful growth factor, and also the most adaptable. Because of its incredible adaptibility, we use relative strength exclusively to manage portfolios. When you compare high relative strength to value, suddenly the tables are turned. Keep in mind that the charts below are generated from the exact same Ken French data library. Value is still defined as high book-to-market, the same data definition that made growth/bad value look like such a nebbish in the last set of charts. But this go round, growth/bad value has been replaced with a worthier opponent, high relative strength.

source: Ken French data library

When it is a fair fight, it’s pretty clear that relative strength is not inferior to value at all. Large cap high RS stocks had a 14.9% compounded return, compared to 13.0% for large cap value. Relative strength also outperformed in the small cap arena, with compounded returns of 20.0%, compared to 18.9% for small cap value.

And, as it turns out, relative strength and value are quite complementary. Their excess returns tend to be uncorrelated, a fact that is remarked on both in Bogle’s book and Brush’s article. Any advisor that has been in the business for a while has seen this effect-both value and growth go through pronounced cycles. Now that we know that both relative strength and value are powerful return factors, and that their excess returns are uncorrelated, what are the practical implications for an advisor?

1) If relative strength is the premier growth factor, it might make sense to replace the growth managers in your stable with managers that use relative strength.

2) Since the excess returns from relative strength and value are uncorrelated, it might make sense to expose clients to both return factors. Brush’s article suggests that a 50/50 mix is the best combination.

So which is better, value or growth? The truth is none of the above. Both are valuable return factors for a portfolio-and because they tend to offset one another, they are even better in combination. If you like, think of the client’s portfolio as a Milky Way bar. Chocolate is good; so is caramel. And together, mmm!

source: Skiptomylou.org

Posted by Andy Hyer

Posted by Andy Hyer