In the U.S. at least, value investing seems to be the approved mode of thought. It could be nothing more than historical accident, but since Graham and Dodd’s Security Analysis is now enshrined in many business and finance programs, it seems likely to continue that way. (It always surprises people to learn that John Bogle’s survey of mutual funds concluded that growth funds had virtually identical performance to value funds.)

The bugaboo of value investing is the so-called “value trap.” It’s a stock that looks cheap, but turns out to be cheap for a good reason and continues to go down or perform poorly. The reason that value investors refer to such stocks as value traps is because they are difficult to identify. After all, if you are buying something because it is cheap relative to various metrics, dropping in price often makes it theoretically more attractive.

Clay Allen of Market Dynamics thinks he knows why many portfolio managers underperform common benchmarks over time: the value traps sneak up on them. In his weekly essay of October 29, he writes:

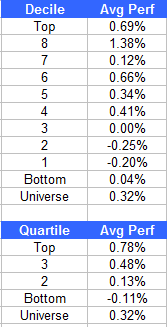

The record of market performance shown by a large number of stocks indicates that as many as 25% to 30% of all stocks show a history of market performance that is worse than the market but not bad enough to force the portfolio manager to face up to the problem. As a result, the long-term investor whose approach is strictly fundamental will not be able to see the persistence of poor performance by many stocks. The long-standing record of poor relative performance shown by 80% of professionally managed portfolios may, in fact, be attributed to value-trap stocks.

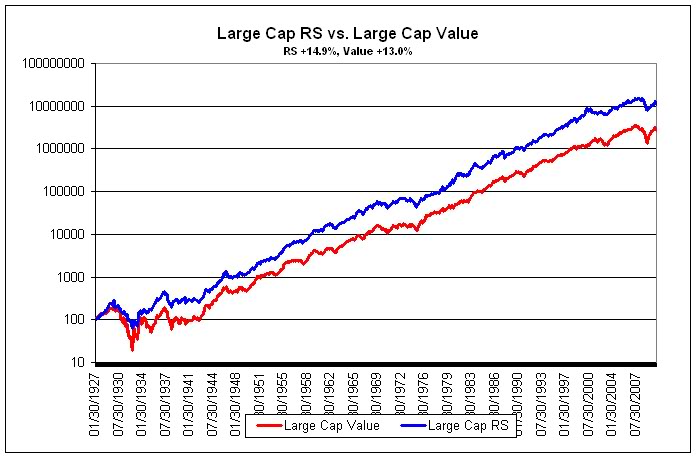

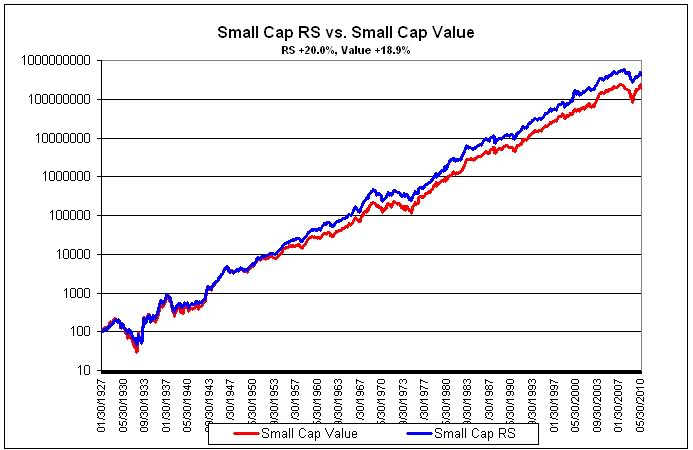

The portfolio process that we use for our Systematic Relative Strength accounts is called “casting out.” The casting-out process is tailor-made for relative strength investing. It requires that we remove an asset from the portfolio when it is no longer highly ranked and replace it with an asset that is stronger. It’s impossible not to face up to a problem stock. The casting out process ensures that the portfolio is always exposed to strong assets, and thus, always exposed to the relative strength return factor. Relative strength is a potent source of returns and by keeping the portfolio focused in strong names, we have a good chance of outperforming market benchmarks over time.

Consider the difficulties of using a casting-out process for value investing. (In fact, many value managers talk about this when they discuss selling a stock to replace it with a better value.) First, you rank everything by value and then buy the items that are cheapest. The items that rise in price often no longer qualify as inexpensive, so they are sold and replaced with better values. The stocks that drop in price, the aforementioned value traps, are retained in the portfolio because they often continue to be very attractive from a valuation standpoint. Think about what happens to the portfolio over a period of time: you sell all of the winners and hold on to the losers! Which, of course, is the exact opposite of what you would like to do. Ouch! Managing a value portfolio well thus generally requires a great deal of discretion. It’s difficult to do systematically. Even good value managers aren’t going to be right about every judgement, and of course there is always inherent market volatility and the periodic investor preference rotation from value to growth and back again to deal with. Research shows that deep value provides excess returns, but the return is tough to capture because of those tricky value traps.

Relative strength investing has an equally aggravating problem: occasionally getting into a trend just as it is ending. Investors get to pick their poison. No method is perfect, but we think because systematic application of relative strength avoids value traps, it might also, just through a happy marriage of the casting-out process with the relative strength return factor, make it a little bit easier to capture the available excess return.

Posted by Mike Moody

Posted by Mike Moody