That’s the provocative title of a recent article in Smart Money. The article makes a controversial claim:

The Journal of Indexes gives academic treatment to bland investments, and so might not seem a likely source of hot controversy. The latest issue, however, is packed with it–and has greatly annoyed mutual fund titan Vanguard. A report therein gives new support for the claim that most index investors are unknowingly missing out on a large portion of the returns that their passive approach ought to provide.

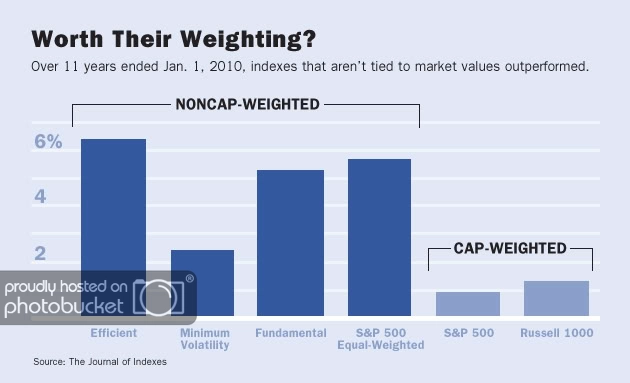

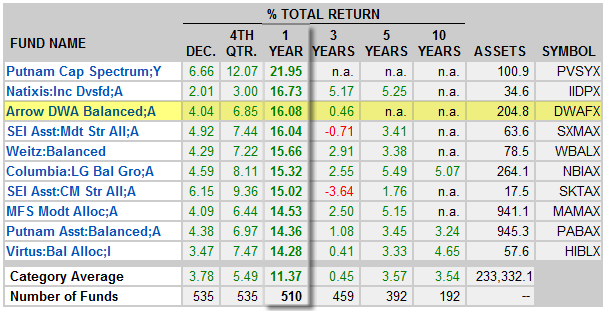

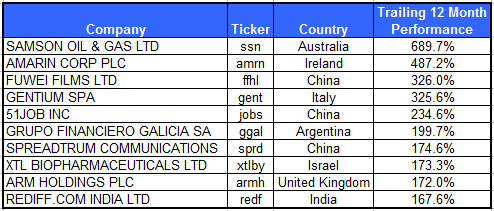

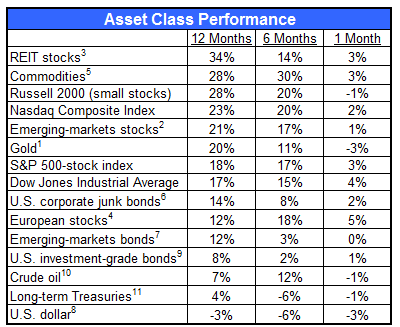

Are investors really missing out on a large part of the passive return? The article implies that a variety of alternative weighting methods like efficiency weighting, volatility weighting, equal weighting, and fundamental weighting provide better returns than traditional capitalization weighting. ETFs are even available for some of these alternative methods, most notably equal weighting (RSP) and fundamental weighting (PRF). Over the eleven-year period cited in the article, all of them have better returns than capitalization weighting.

Source: Smart Money/The Journal of Indexes

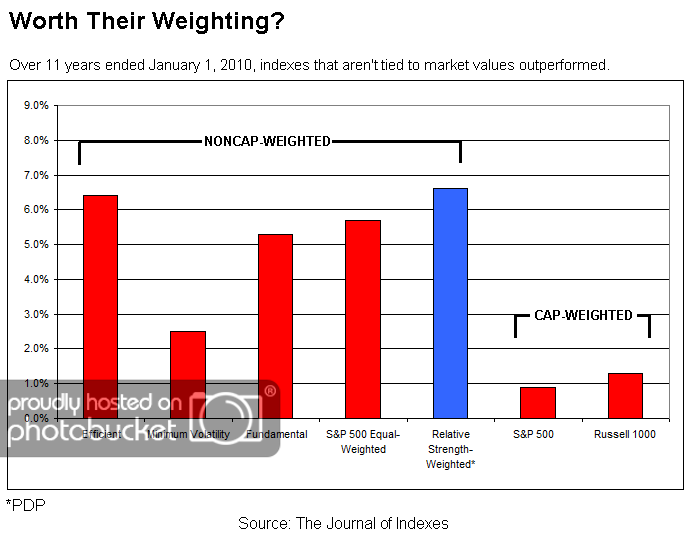

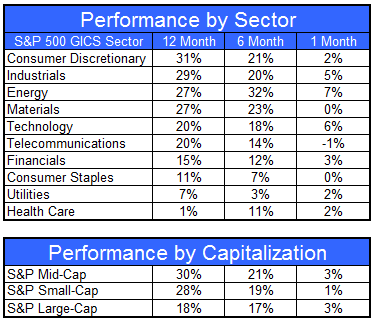

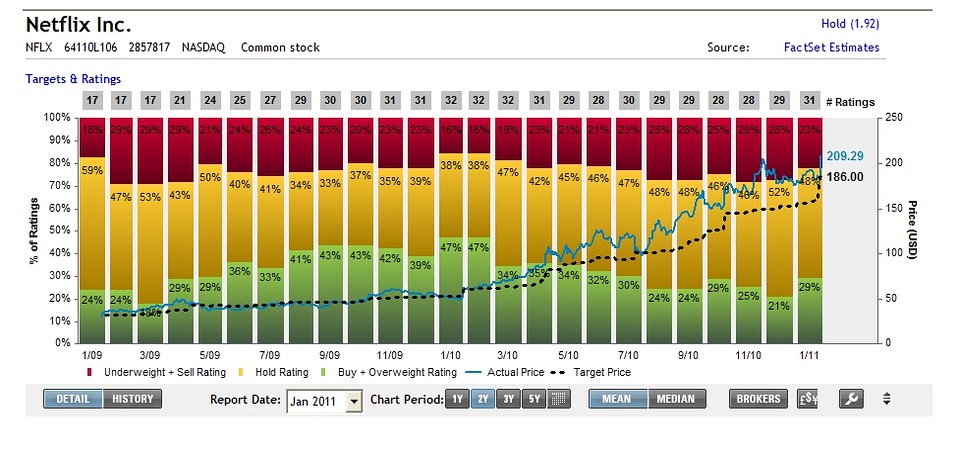

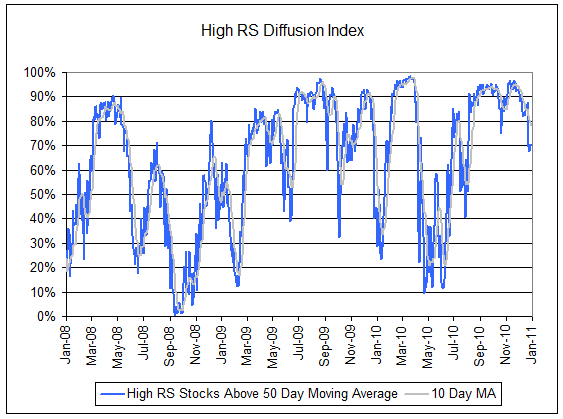

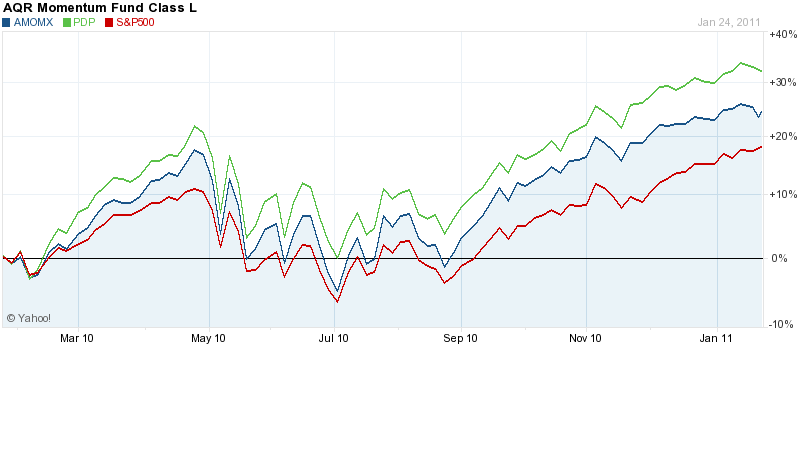

Here’s what drives me crazy: when alternative weighting methodologies are discussed, there is always one method omitted. That method is relative strength. Perhaps it is no surprise that over the eleven-year period cited in the article, relative strength weighting outperformed all of the other methods. (And I didn’t get to cherry pick the time period–the article made that choice. If the blowout year of 2010 was included in the results, relative strength would have an even larger advantage over its rivals.) It’s also nice to note that there is a relative strength weighted index available, the Technical Leaders Index (PDP). Here’s what the same chart looks like if relative strength weighting is included.

Source: Journal of Indexes, Dorsey Wright

Why is relative strength weighting always left out? If I were cynical, I might say that relative strength is intentionally disregarded so that alternative methodologies do not have to show their comparative performance. But since I am in a charitable mood, I think the reason it is often ignored is because it is too simple. Yes, too simple.

It does not require manipulation of a massive fundamental database. It does not require equations and a mainframe computer to calculate a covariance matrix. It does not require a CFA, MBA, or PhD. (Think how much money you could save on grad school!) Instead, it requires a pocket calculator or spreadsheet and one of the many methods for measuring relative strength. We are partial to our proprietary measurements, but lots of methods work just fine. What does it say about your complicated alternative indexing method when it can be outperformed by something a middle-school student could learn to calculate?

There is one big advantage to capitalization weighting: it can be implemented in nearly infinite size. Along with theoretical reasons (“owning the market portfolio” in Modern Portfolio Theory), that may well be one reason why institutions, and Vanguard, believe it is the way to go. On the other hand, it is not really a stretch to believe that there are alternative indexing methodologies that could be designed for better performance. We think that relative strength has been demonstrated to be the simplest and most robust way to build the better mousetrap.