Our latest sentiment survey was open from 5/6/11 to 5/13/11. The Dorsey, Wright Polo Shirt raffle continues to drive advisor participation — thank you for taking the time! Please remember, the first drawing will be held on June 1, so keep playing to increase your odds of winning. This round, we had 127 advisors participate in the survey. If you believe, as we do, that markets are driven by supply and demand, client behavior is important. We’re not asking what you think of the market—since most of our blog readers are financial advisors, we’re asking instead about the behavior of your clients. Then we’re aggregating responses exclusively for our readership. Your privacy will not be compromised in any way.

After the first 30 or so responses, the established pattern was simply magnified, so we are comfortable about the statistical validity of our sample. Most of the responses were from the U.S., but we also had multiple advisors respond from at least five other countries. Let’s get down to an analysis of the data! Note: You can click on any of the charts to enlarge them.

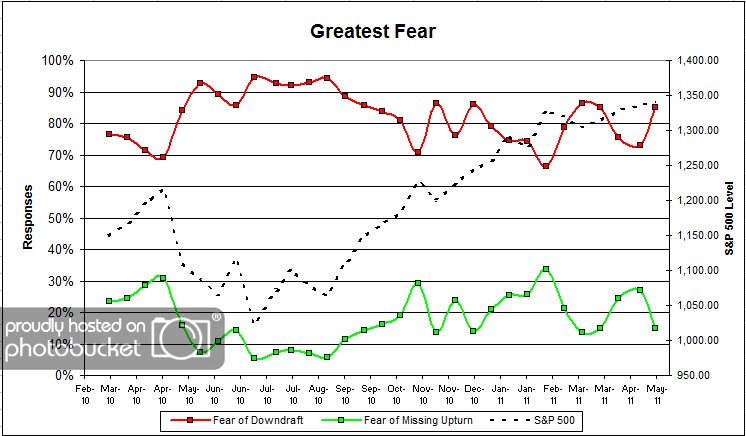

Question 1. Based on their behavior, are your clients currently more afraid of: a) getting caught in a stock market downdraft, or b) missing a stock market upturn?

Chart 1: Greatest Fear. From survey to survey, the S&P was up fractionally (+0.3%). However, recent volatility in the broader market (especially commodities) seems to have sent client fear levels soaring. This round, client fear levels shot from 73% to 85%. On the other side, the missing opportunity group fell from 27% to 15%.

Keeping in mind that the market did fluctuate after the official date we’ve set for the survey results, client fear levels are at 85% - yet the stock market is at all-time survey highs. The S&P 500 is up over +30% since July of 2010, yet client psychology remains heavily skewed towards fear of a downdraft.

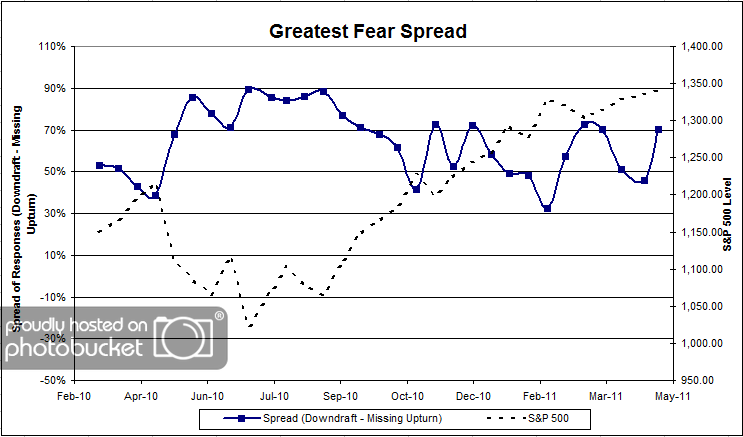

Chart 2. Greatest Fear Spread. Another way to look at this data is to examine the spread between the two groups. The spread jumped this round from 46% to 70%.

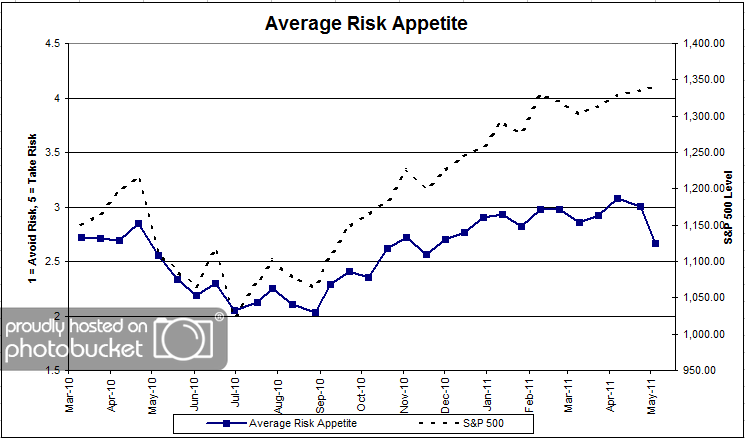

Question 2. Based on their behavior, how would you rate your clients’ current appetite for risk?

Chart 3: Average Risk Appetite. Average risk plummeted this round, from 3.01 to 2.66. Here again, we see a huge disconnect between what’s happening in the market from survey to survey, versus client sentiment. The market is still up big over the medium to long term (6 months to 2 years). Why is client risk appetite stuck below 3? Only time will tell just how big of a rally it’s going to take before we see more aggressive client participation.

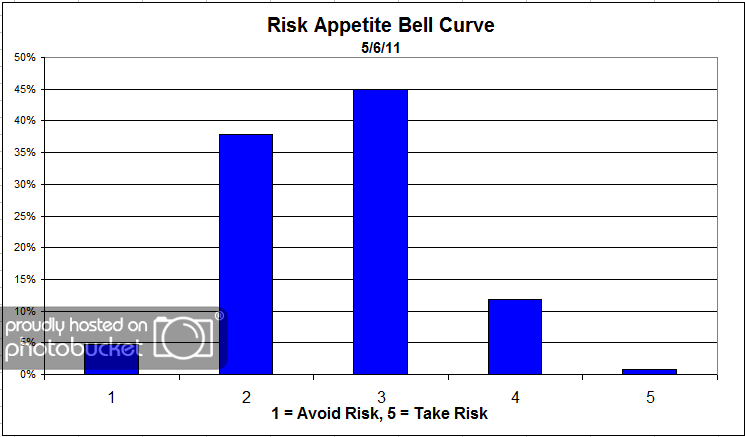

Chart 4: Risk Appetite Bell Curve. This chart uses a bell curve to break out the percentage of respondents at each risk appetite level. Here we see more evidence of fearful clients, with the majority of respondents answering 2 and 3 (over 82% of all clients, combined).

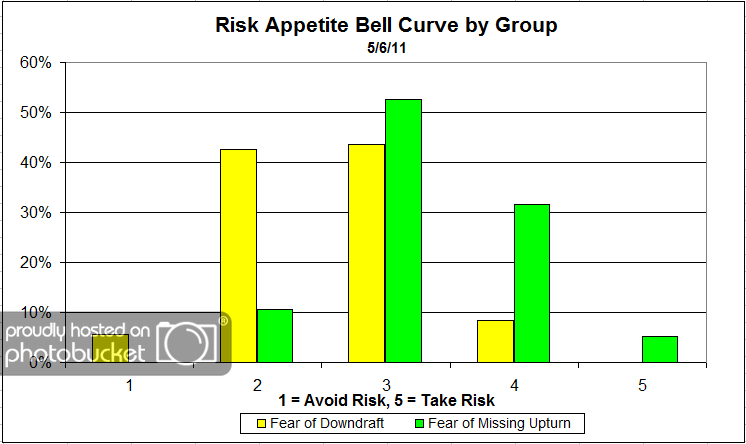

Chart 5: Risk Appetite Bell Curve by Group. The next three charts use cross-sectional data. This chart plots the reported client risk appetite separately for the fear of downdraft and for the fear of missing upturn groups. This chart sorts out perfectly, save one person in the missing upturn group who desired a risk appetite of 1. The fear group is looking for lower risk (3′s through 1′s), while the opportunity group is looking for more risk (3′s through 5′s).

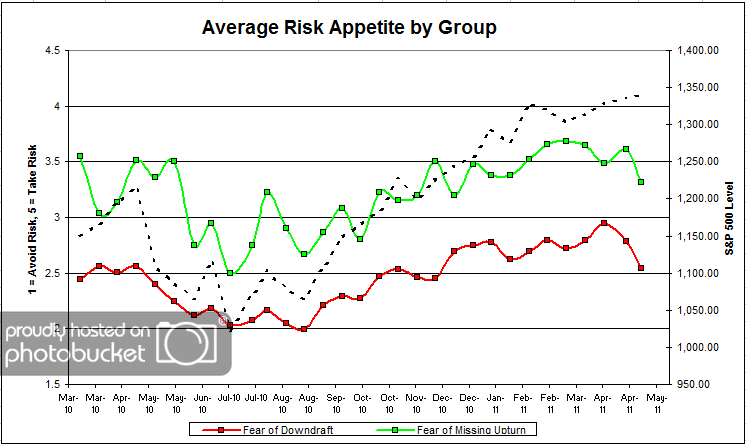

Chart 6: Average Risk Appetite by Group. The average risk appetite by group chart reflects what we saw in the overall risk appetite chart from above — a sharp move away from risk, in both camps. Again, from survey to survey the market is doing fine. It appears that the volatility outside the stock market-in other markets such as commodities and the US dollar— has shaken up client sentiment significantly.

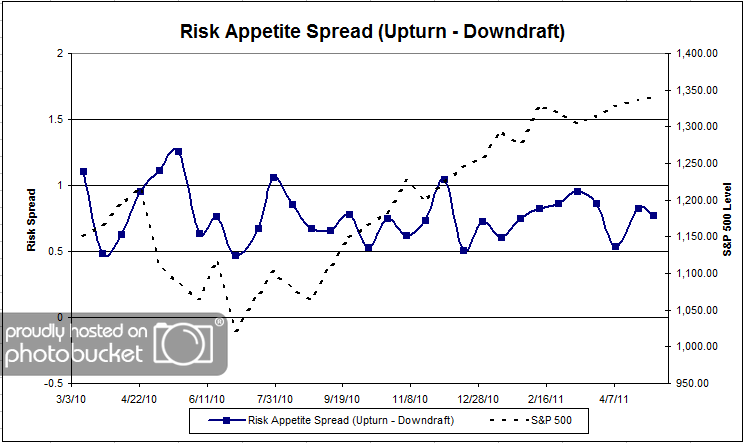

Chart 7: Risk Appetite Spread. This is a spread chart constructed from the data in Chart 6, where the average risk appetite of the downdraft group is subtracted from the average risk appetite of the missing upturn group. Despite big moves in the both camps, the spread remained mostly the same this round.

This round, the market rallied around +0.3% from survey to survey, but client fear levels rose significantly on market volatility. We would expect that, as the market continues to rally, fear levels subside and clients begin to add more risk. However, it’s obvious that clients are still more worried about losing money than about losing the opportunity to make money. We hyphothesize that eventually, the tide will swing in the other direction once the market has tacked on strong gains over a number of years.

No one can predict the future, as we all know, so instead of prognosticating, we will sit back and enjoy the ride. A rigorously tested, systematic investment process provides a great deal of comfort for clients during these types of fearful, highly uncertain market environments. Until next time, good trading and thank you for participating.

Posted by JP Lee

Posted by JP Lee