Matt Koppenheffer nicely makes the case for holding on to your winners and cutting out your losers (exactly what relative strength is designed to do):

When it comes to investing, there’s no shortage of bad advice floating around out there. Among the worst, though, is the old saw, “You can’t go broke by taking a profit.”

The saying refers to the belief that if you have a stock that’s gone up in value, it’s hard to go wrong selling that stock and “locking in” the gains. But while the saying is technically true — it’s hard to picture a scenario where an investor is suddenly bankrupt after selling a stock at a profit — it’s a dangerous platitude for investors to follow.

There’s a name for that

The practice of selling winning stocks and hanging on to losing ones is a practice that’s familiar to behavioral-finance experts. It’s a behavioral bias known as the disposition effect and has been revealed to be quite harmful for investors. A number of academic papers have shed light on the subject, including Berkeley professor Terrance Odean’s 1998 study that concluded that individual investors’ “preference for selling winners and holding losers … leads, in fact, to lower returns.”A possible explanation

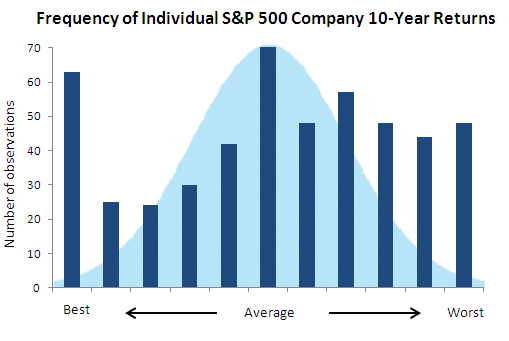

If the long-term returns from stocks were distributed normally — that is, they formed the familiar bell-shaped curve and most stocks’ returns clustered around the average — selling winners and holding losers might actually work. If the returns from most individual stocks were likely to be right around the average for all stocks, then a big winner would be more likely to stall out after its winning streak than continue climbing. At the other end, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to expect a stock that’s been a big loser to climb back closer to the average.But that’s not how it works.

I was reminded of this by a recent report by Shankar Vedantam for NPR, called “Put Away the Bell Curve: Most of Us Aren’t Average. Vedantam reviewed the research and work of Ernest O’Boyle Jr. and Herman Aguinis, who studied the performance of 633,263 people involved in academia, sports, politics, and entertainment.

In short, the pair’s finding was that the performance distribution in these groups wasn’t bell-shaped. Instead, many participants clustered below the mathematical average, while a group of superstars produced results far above the average and pulled the overall average up.

Stock returns have a similar distaste for fitting to a bell curve. Over the past 10 years, 63% of the S&P 500 companies underperformed the average. Meanwhile, a large group of significant outperformers delivered returns that were well above the average.

As compared with the bell curve in the background, the data plotted here is a mess. And it should be. Stock returns are not normally distributed — which is what produces that nice bell-shaped curve. And though stats-stars who are much smarter than me often try to describe stock returns as “lognormal” — a mathematical transformation of the returns that gets them to more closely fit a bell curve — they’re not that, either. Stocks are typified by “fat tails” on either end — that is, more seriously outperforming and underperforming stocks than is easily captured by streamlined mathematical models.

So no matter how you look at stock returns, a surprising number of stocks end up returning far more and far less than the average. Practically, this means that the practice of “locking in gains” and hanging on to losers is a good way to miss out on the market’s huge outperformers, stay stuck with poor performers, and earn lackluster overall returns.

HT: iShares

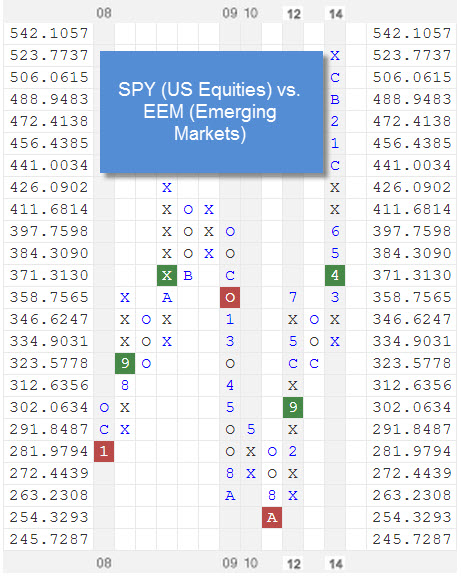

This first appeared on our blog in May of 2012. Recent trends in Energy (down) and Healthcare (up) brought this to mind. Fat tails are a market reality-invest accordingly.