When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir? -John Maynard Keynes

Although their theories seem to be no more or no less accurate, British economists always seem to have better quips than other economists. At the same time, Keynes brings up an important point. What do you do when the facts change-and how do you know if the facts have changed?

CSS Analytics has an interesting post on this subject today. The author points out a problem with forecasting:

The strangest thing about the forecasting world is not that it is a dismal science (which it is) but rather that forecasters share some remarkably primitive biases. Whether you look at purely quantitative forecasts or “expert/guru” forecasts, they have one thing in common: they rarely change their opinions or methods in light of new information. In fact, what I have noticed is that the smarter the person is and the more information they seem to possess, the less likely they are to change their mind. Undoubtedly this is why many genuinely intelligent and knowledgeable experts have blown up large funds or personal trading accounts.

It wouldn’t be so sad if it weren’t true. This lack of adaptability wiped out even a couple of Nobel Prize winners at Long Term Capital Management. The problem really is one of properly structuring one’s decision framework. CSS Analytics observes:

Ask a person to give you an opinion on where a market is going, and then notice what happens when the market goes dramatically the other way along with news announcements that seem to conflict with their thesis. Most of the time this person will tell you that they have not changed their mind, and in fact that it is an even better price to buy (or short). Models or systems suffer from the same problem–they typically do not adjust as conditions or regimes change…

Here, the decision framework is fixed. Since humans are naturally wired to seek out confirming evidence and to ignore disconfirming evidence, that is what happens. All evidence begins to be massaged to support the opinion, which is assumed to be correct. The story from CSS Analytics below is sadly familiar to most investors, almost all of whom start out as value investors:

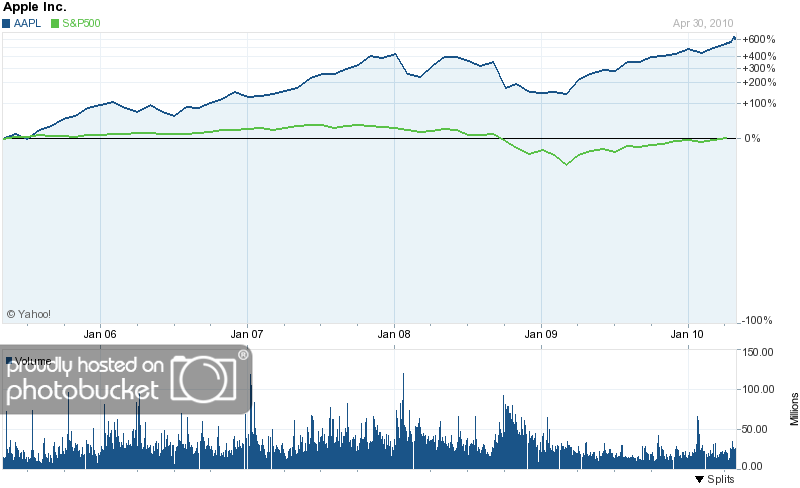

I spent my early investing experiences as a “value investor” and let me tell you that I learned the hard way many times that the market was more often right than wrong. It was uncanny how well future fundamentals were sometimes “forecasted” by price. At the time, I had no knowledge of technical analysis and lacked the intellectual framework to synthesize a superior decision-making method. Of course, I would ride that “under-valued” stock with a price to book ratio less than 1 all the way to being a penny stock before I gave up. I also sold many of my winners far too early because their P/E indicated they were no longer undervalued. Some of these stocks went on to go up 400% or more, while I was content to make 25% profit. I did the exact opposite with overvalued stocks or stocks with crappy fundamentals. I was heavily short Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as well as General Motors in early 2007! Of course, I got my clock cleaned and got margin-calls long before they plunged almost to zero. This was a case of being right, but too early to fight the sentiment of the crowd.

As a wise man once said, “Being early is indistinguishable from being wrong.” Even knowing that we should avoid a fixed decision framework, however, doesn’t really get us any closer to knowing how to handle the forecasting problem. CSS Analytics describes their epiphany:

It finally dawned on me one day that good forecasting (or decision-making) was a dynamic process involving feedback. In fact, the actual information used to make the initial decisions need not be complex as long as you are willing to adjust after the fact.

I put the whole thing in bold because I think it’s that important-although I don’t think our systematic relative strength process is forecasting at all. It’s simply a decision-making framework that incorporates a specific kind of feedback: the most important feedback to an investor, which is price. Price change tells you whether your decision is working out or not. If something isn’t working, you kick it out of the portfolio-that’s adjusting after the fact. Price is not complex at all, but it is the one mission-critical piece of feedback that is needed because that’s how every investment is measured.

Investing is one of those weird fields where clever opinions are often more valued than results. Certain gurus still get media exposure and sell hordes of newsletter subscriptions because subscribers agree with their bullish or bearish opinions, even though an outside service like Hulbert can demonstrate that their actual performance is abysmal. In professional sports, if you suck, you get released or sit on the bench. If you really suck, you don’t make the roster in the first place. Sometimes, in the investment field, if you really suck, you get to be on CNBC and have well-coiffed, polite hosts take your opinions seriously.

I think the description of good decision-making as a dynamic process involving feedback is very concise. Incorporating feedback is what makes a model adaptive. Models that are based on historical data ranges blow up all the time for this very reason-they are, in effect, optimized to the historical data but cannot always incorporate feedback. Continuous measurement of relative strength is not unlike former New York City mayor Ed Koch’s greeting, “How am I doing?” If the answer is ”not well,” then it’s time to ditch that asset and replace it with another one that has the prospect of better performance. The beauty of a relative strength model is that when the facts change, it changes its mind.