Morningstar ran a recent skeptical look at momentum as a return factor. The author, Shannon Zimmerman, was upfront about his bias as an analyst:

As an analyst, I’m a fundamentalist at heart, focusing primarily on fund managers whose success owes to bottom-up research and strict valuation work.

Still, he tried to give relative strength (known in academia as “momentum”) a fair look, especially since strict valuation work was notably unsuccessful. He notes:

It’s a fascinating topic, particularly for those who favor fundamental money managers, a group that, on average, has generally lost to the relevant bogies. Contrary to that track record, the data on price momentum seem to show remarkable long-haul success.

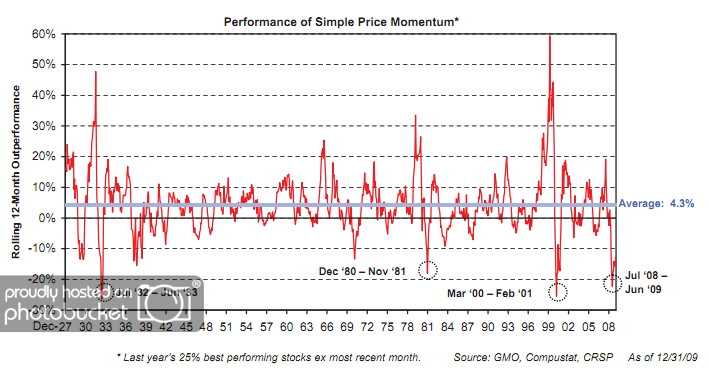

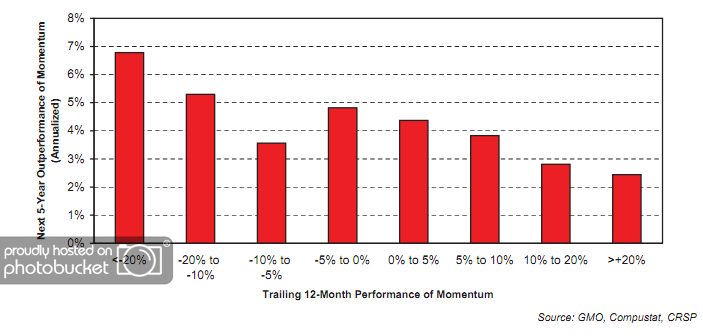

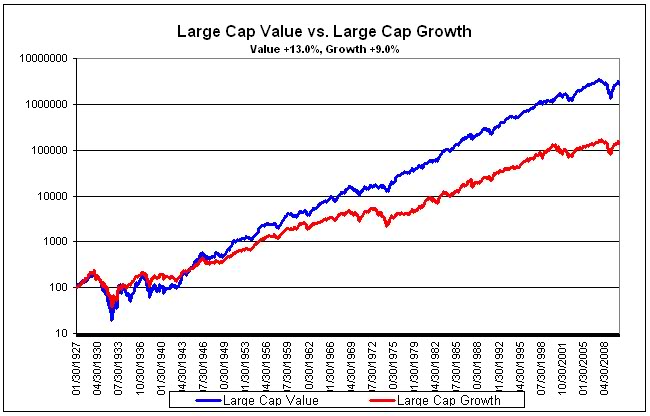

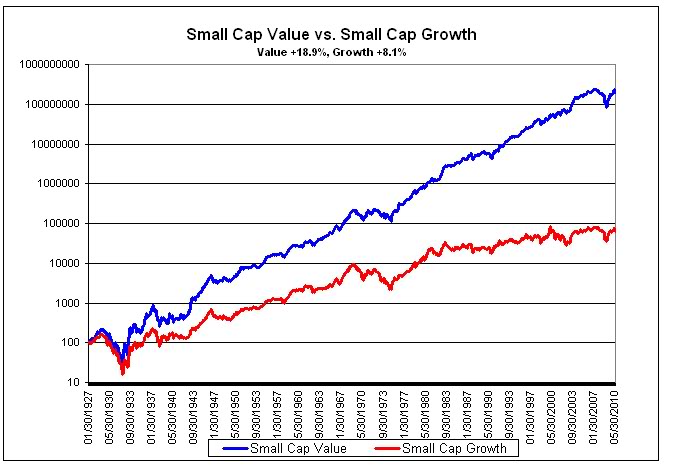

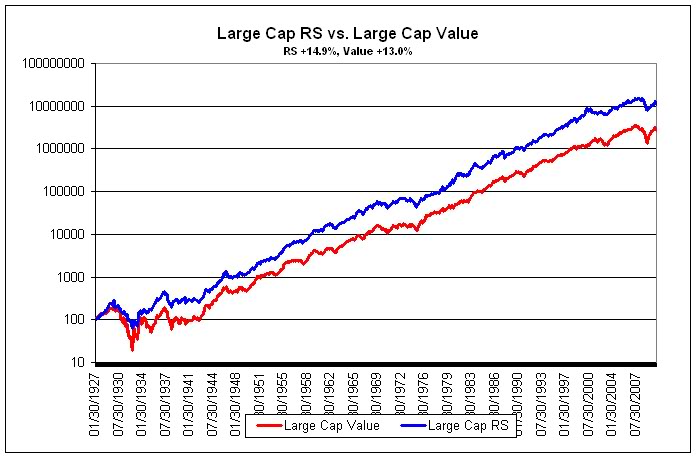

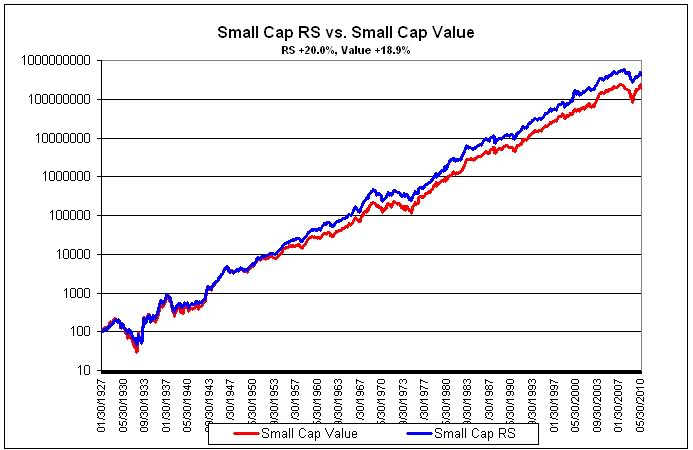

Then he brings up a couple of straw men to explain why relative strength may not really work. First, he suggests that the high returns from momentum may be concentrated in a few short periods of time—more on this later— (like the famous small-cap advantage over large caps) or that it may be a function of style.

In addition to time-series static, for example, how much of momentum’s long-haul outperformance may owe to style? Has the tactic’s showing been powered by pockets of success in, say, growth stocks or mid-cap names?

Fortunately for the home team, Ibbotson completed a recent research paper on that very topic. And what did they find?

…the conclusion is striking: Regardless of where in the style box they reside, portfolios comprising funds that provide the greatest level of exposure to high-momentum stocks significantly outperform those with the lowest levels.

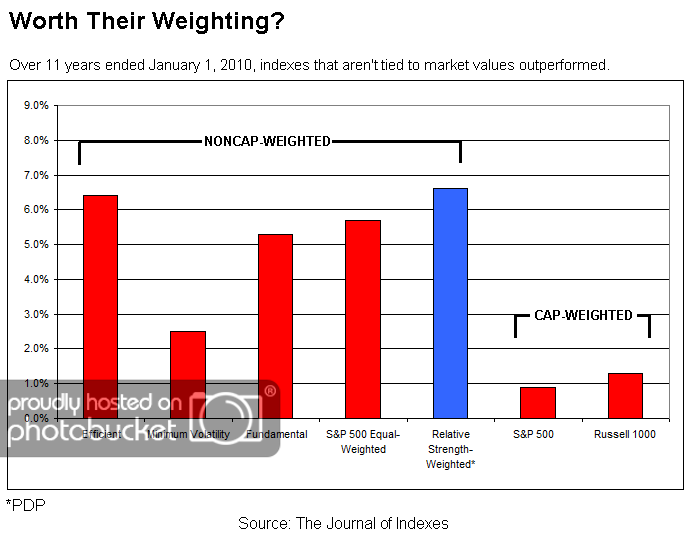

While this may be surprising to a fundamentalist, this is no surprise at all to those of us that have been delving through relative strength research for many years. Relative strength seems to be a universal return factor, present in domestic and international securities—and even global asset classes. Clearly, Ibbotson showed that it was present in every style box.

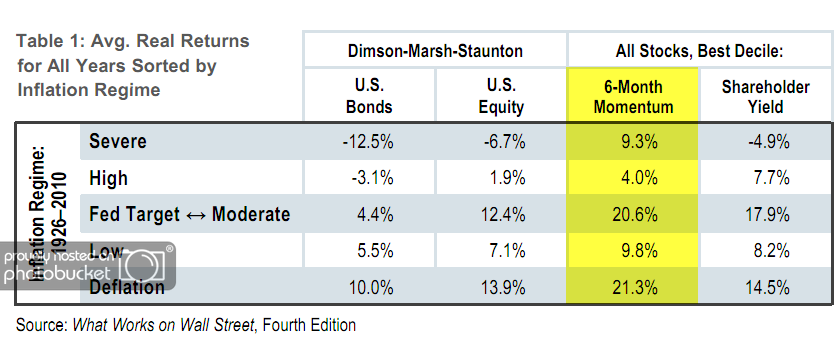

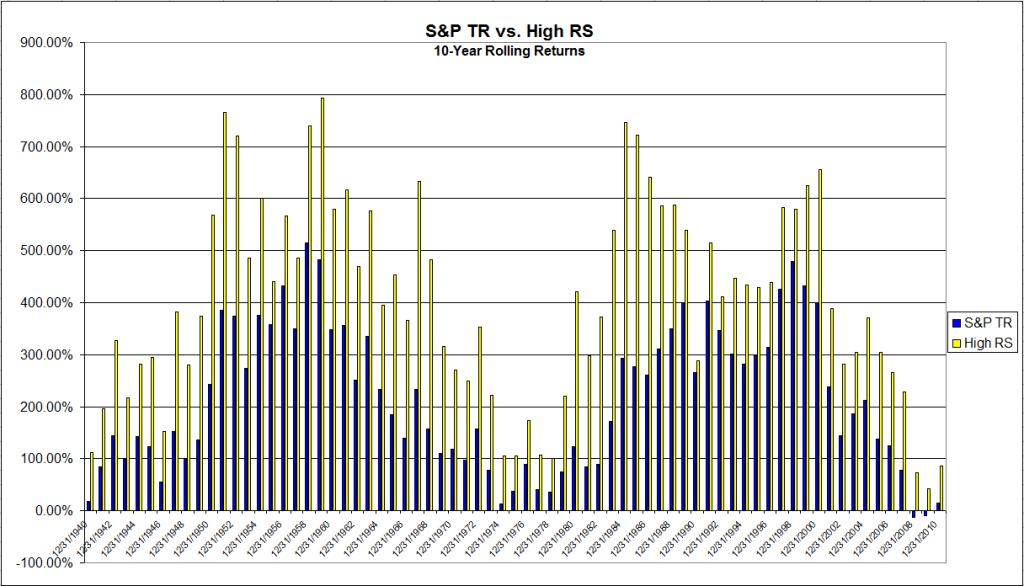

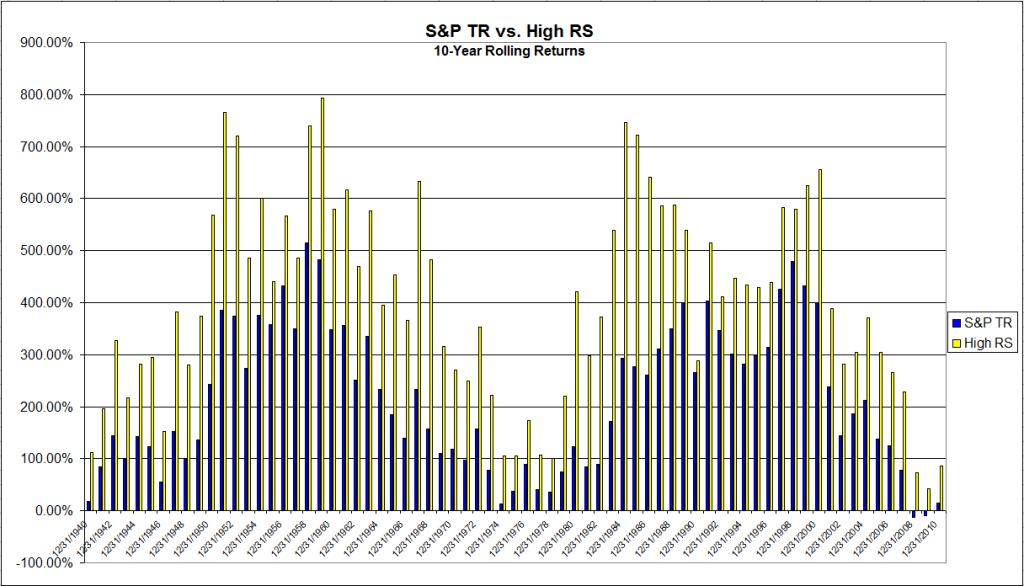

As for the time concentration issue, not to worry. We tracked down total return data for the S&P 500 going back to 1930 and compared it to the momentum series on the website of Ken French at Dartmouth (top half in market cap, top 1/3 in momentum). Ironically, Ken French is one of the leading apologists for the efficient market theory. The chart below shows 10-year rolling returns, which is why it starts in 1940. The average ten-year returns? 405% for relative strength and 216% for the S&P 500, a near doubling! That’s without the momentum series getting any credit for dividends. Even more impressive, the ten-year rolling return of the relative strength series outperformed in 100% of the time periods. Clearly, unlike the small-cap versus large-cap issue, relative strength performance is not limited to certain narrow time periods.

Click to enlarge

Source: J.P. Lee, Dorsey, Wright Money Management

Why are value investors always so shocked by the strong performance of relative strength methods? I think there are two major reasons: 1) the value cult has drowned out discussion of other successful return factors, and 2) the reason for strong momentum is poorly understood.

The value cult drowns out other schools of investing, but it developed its following largely by historical accident. Ben Graham and David Dodd’s classic Securities Analysis came out early on, in 1934, and found a vocal contemporary advocate in Warren Buffett. In other words, much of the historical prominence of value investing is due to its early start—and the fact that it developed and was propagated in academia, where it had a chance to be taught as the shining, virtuous path to wealth to generations of students. Its tenets were never really questioned bacause value investing is also logical, pretty transparent, and it works. However, it is a logical mistake to assume that since value investing works, it is the only thing that works.

Largely overlooked by the value cultists is the fact that Warren Buffett’s fortune has been made in growth stocks with high reinvestment rates and arbitrage, not cigar butts. From James Altucher’s book Trade Like Warren Buffett: “…Buffett achieved much of his early success from arbitrage techniques, short-term trading, liquidations, and so on rather than using the techniques he became famous for with stocks like Coca-Cola or Capital Cities. In the latter stages of his career he was able to successfully diversify his portfolio using fixed income arbitrage, currencies, commodities, and other techniques.” (Note: when Buffett purchased his stake in Coca-Cola, it carried a P/E of 13, while the overall market was selling for a P/E of 10! Not exactly a traditional value investment.) In recent years, Buffett has become famous for a giant derivatives trade where he essentially wrote a massive amount of naked put options on the U.S. market. In other words, the popular image of Warren Buffett as a buy-and-hold value investor is completely false. I’m not bashing here—Warren Buffett is clearly a great investor, and while he did take Ben Graham’s course at Columbia, much of his success is due to his investment flexibility, not some imaginary ability to identify value stocks and then hold them forever.

Likewise, Ben Graham made no secret of the fact that his personal fortune from the Graham-Newman Corporation was, in fact, due to the growth stocks purchased by his partner Jerry Newman. One magazine article I read quoted the anointed father of value investing, Benjamin Graham, as saying “Thank God for Jerry Newman! If it weren’t for him, we never would have made any money.” Based on the real lives of Buffett and Graham, profitable investing is a little more complex than reading The Intelligent Investor a few times, and clearly not limited to any strict definition of value investing.

Once value cultists concede that successful investing can be done in several ways, we’re left with trying to understand why relative strength works. Why do stocks that are strong tend to stay strong for a while? Simply put, strong stocks are typically in a sweet spot, either on a fundamental or macroeconomic basis. High RS stocks generally have tremendous current fundamentals.

Let’s look at a current example—the best performing stock in the S&P 500 last year, Netflix. In a moribund economy, the year-over-year change in revenues at Netflix accelerated from 19% growth in Q4 2008 to 34% growth by Q4 2010. While revenues were increasing 34%, earnings per share went up 55%, which indicates that margins were expanding. Investors, for some reason, were attracted to a stock with rapid and accelerating revenue growth and profit margins. Is that really so difficult to understand?

Can Netflix continue to accelerate revenues and margins? The laws of mathematics tell us that this feat cannot be pulled off forever—but it’s already gone on for a couple of years and that’s certainly long enough to make a lot of money. How much longer it will continue is anyone’s guess. (Certainly it has gone on longer than Whitney Tilson expected.) The high relative strength investor looks for stocks that are performing—but stays with them only as long as that performance continues. At some point, Netflix will hit a speed bump, and when it does, the high relative strength investor will happily part with the shares—hopefully at a tasty profit.

Lots of practitioner and academic studies show this exact pattern: if you hold strong assets and ruthlessly replace assets that become weak, the portfolios do very well. There’s really no mystery to it.

So, Mr. Zimmerman, if you’re reading this, don’t beat yourself up. I’m sure you’re a great guy. You’re not the first value investor that has had trouble understanding how relative strength operates as a return factor. And you should take heart in this: studies show that portfolios combining relative strength and value have uncorrelated excess returns, so it works great to have a mix of both styles. Value works, but relative strength rocks.