Most readers of Systematic Relative Strength are aware of our high esteem for relative strength. But they may not be aware of the nearly criminal neglect of relative strength in finance-for reasons shrouded in history. Perhaps over time that mystery will be solved, but this is one view of it.

Relative strength has deep historical roots in financial market analysis. Prominent technical analysts like Richard Wyckoff and H.M. Gartley wrote books in the 1930s that discussed relative strength (among other things) and made it clear that the practice of examining relative performance was not new even then. Richard Wyckoff used it to make a fortune in the stock market, retiring to an estate in the Hamptons next to Alfred E. Sloan, the legendary chairman of General Motors. George Chestnutt, the iconic manager of the American Investors Trust, compiled the best mutual fund track record of the 1960s using relative strength-and did not flame out in the 1970s like many other managers from the go-go years. Technical analysis failed to profit much from its association with relative strength, however. Over the years, warm-hearted technical analysts welcomed market strays promoting all sorts of esoteric waves, angles, retracements, ambiguous patterns, and even astrology into their tent. Even though there were still plenty of excellent practitioners, the further technical analysis strayed from actual market-generated data and testable hypotheses, the more its credibility as a profession slipped. To understand how relative strength had its identity stolen, it makes sense to revisit the scene of the crime.

A uniquely American school of thought from the 1930s was fundamental security analysis, best exemplified by Benjamin Graham at Columbia University. His idea was that an intrinsic value could be placed on a company, so that it could be readily determined if a security was undervalued or overpriced. This was much more scientific than speculative buying on margin based on rumor or inside information. Security analysis quickly gained adherents in the investment community, even as valuation metrics proliferated, some having little to do with value in a way Benjamin Graham would recognize.

Another milestone in finance came in 1952 when Harry Markowitz pioneered Modern Portfolio Theory. In a paper published in the Journal of Finance, he discussed the mathematics behind the effects of asset risk, return, and correlation in the construction of an optimal portfolio. Academia swooned and the rout for relative strength was on.

Fundamental analysts quickly allied themselves with the academic community, although the marriage was always a little problematic. After all, how do you reconcile the notion that the market is efficient with the idea that you can identify undervalued securities?

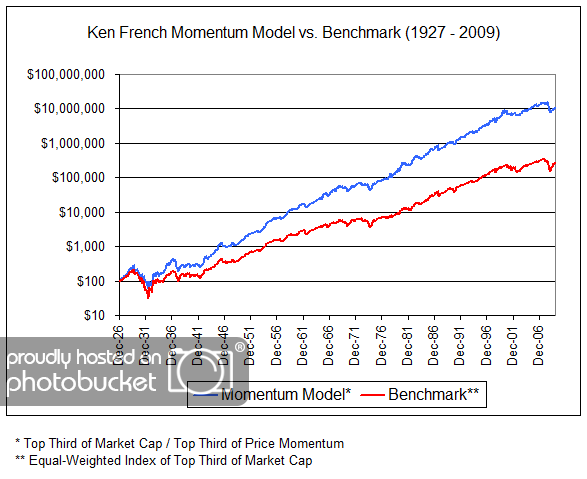

In time, anomalies popped up in efficient-market land. For example, Eugene Fama and Ken French discovered that there were performance differences between large-cap and small-cap stocks. Even Fama and French, however, didn’t know what to do with relative strength. According to James Picerno in his wonderful article “Bodies in Motion:”

Professors Eugene Fama and Ken French cited the momentum factor as an “embarrassment” for their own popular three-factor asset pricing model, which identifies small and value stocks, along with the overall market, as the primary risk factors driving equity returns. Fama and French couldn’t explain the success of momentum investing, even if they did acknowledge its existence.

Unfortunately for relative strength, some of the research was sloppy. For example, numerous studies were published purporting to show performance differences between growth stocks and value stocks. Value stocks always won, evidence that, taken on its face, seemed to validate the value-oriented security analysis crowd. Since relative strength had always been viewed more as a growth factor, this outcome was particularly damaging to the reputation of relative strength.

Closer examination of the studies revealed a serious flaw in their construction. The stock universe used was typically segmented by some valuation ratio, with the good value stocks classified as “value” and the bad value stocks getting thrown into the “growth” category. It took John Brush to point out that growth was not the same thing as bad value. His re-examination of the data showed that growth factors actually outperformed value factors over time.

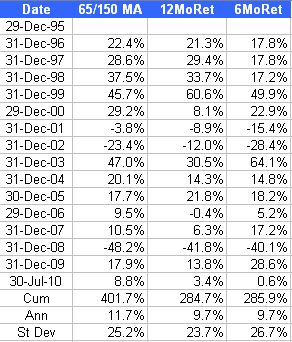

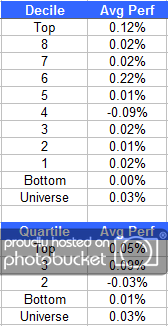

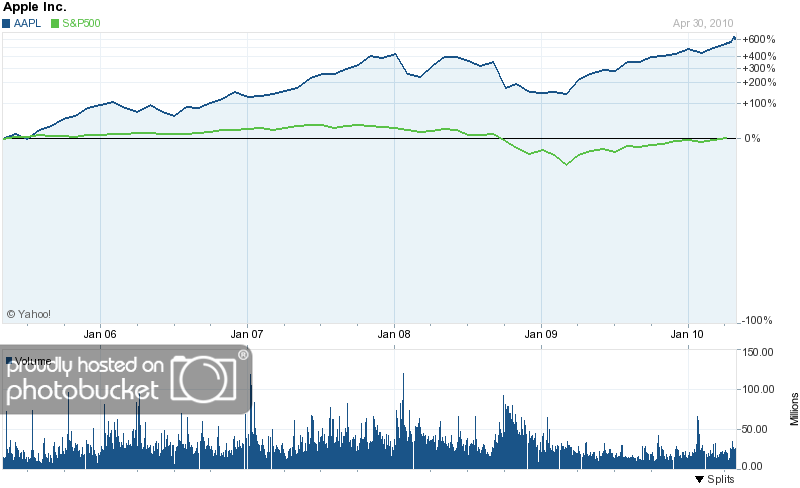

In 1967, an American University graduate student named Robert Levy did the first computerized testing of relative strength as a return factor. His article, “Relative Strength as a Criterion for Investment Selection,” in the Journal of Finance, soon followed by a book, was earthshaking. Academia, still in the thrall of efficient markets, shouted him down. How dare he show that a simple momentum factor could consistently outperform the market? Levy left the investment field-but his relative strength return factor continued to work, as was shown in subsequent papers, like our own 2005 article published in Technical Analysis of Stocks & Commodities magazine.

Unfortunately for Modern Portfolio Theory, anomalies continued to proliferate to the point that they were perhaps more frequent than the things that worked according to theory. Academics were emboldened to explore new avenues, one of which was really an old friend, relative strength. Given the reception that Levy had received, modern academics thought it perhaps wiser to rechristen the return factor as “momentum.”

The first academic papers on momentum began appearing in the early 1990s, alongside more popular treatments of relative strength like James O’Shaughnessy’s What Works on Wall Street. Even so, discussions of relative strength still took a backseat to value-oriented anomalies. When I went to the first conference on behavioral finance held at Harvard University in 1997, the crowd was captivated by Josef Lakonishok and his presentation of investor over-reaction and under-reaction, I suspect because it fit in very nicely with the contrarian/value bias of most of the conference attendees. In contrast, when Lakonishok later presented his paper on momentum at the same conference, the crowd was sparse and uninterested.

Very recently, relative strength has garnered new attention. In an outstanding article in Financial Advisor, James Picerno traces some of the history of momentum as a return factor:

Since it was formally revived in the academic literature for the first time in the early 1990s, there’s been a wide-ranging debate about why momentum investing exists and what it means for modern portfolio theory. Yet now there’s a growing acceptance of it as a separate and distinct driver of return premiums.

As a gauge of institutional acceptance, Morningstar recently announced plans to include momentum as a return factor and will begin to rate funds by the average level of momentum in the holdings as well. (It should be noted that quantitative analysts did not ignore Levy’s groundbreaking work. Quants long ago confirmed relative strength as a return factor, which is why it is now ensconced in nearly every multifactor model.)

This re-acceptance of relative strength, as Picerno points out, is well-grounded:

The concept of momentum investing is compelling not just because investors are hungry for diversification and new strategies but also for it’s durability in the real world. Relatively few other strategies survive the transition from paper to real-world portfolios the way momentum investing does.

In the textbooks, minting profits looks easy because the standard asset pricing theory suffers from so-called return anomalies—sources of excess returns above and beyond what’s implied by the academic models. But exploiting these anomalies in actual portfolios is hard. Trading costs, taxes and other frictions take a toll. And many profitable return patterns that look solid in the financial laboratory have an annoying habit of disappearing when the crowd comes rushing in.

Is momentum investing different? It appears to be. Academics and money managers tend to agree that it is a resilient source of return that stands up to the usual lines of attack, such as criticism that it’s simply a byproduct of data mining or that it’s vulnerable to arbitrage. It doesn’t hurt that the basic idea is as old as investing itself and so it’s stood the test of time.

Relative strength also turned out to be a universal factor. It worked not just for U.S. stocks, but for asset classes, and for all manner of foreign markets. Picerno writes:

“Momentum is ubiquitous across all major asset classes,” says professor Craig Pirrong at the University of Houston, summarizing the conclusion in one of his own research efforts.

A similar finding echoes throughout the analysis of Mebane Faber, a portfolio manager at Cambria Investment Management. His work demonstrates that momentum investing’s close cousin—trend following—has proved its worth as a risk management tool in connection with tactical asset allocation.

What’s the point in our forensic analysis of the scene of the crime? What can we take away from this tale of intellectual kidnapping, of eclipse and re-emergence? There are several useful lessons, I think.

First, respect history. Don’t be too quick to dismiss the “primitive” ideas of your predecessors. They may not have had the same technological tools as we do now, but that doesn’t mean their IQ was lower. Relative strength was based on close observation of markets and actual human behavior, and ironically, it has turned out to be much more sturdy than the equations and the rational man of Modern Portfolio Theory. The only thing new under the sun is the history you haven’t read yet.

Second, evidence trumps assertion. Don’t believe everything you read. Test it yourself. Levy’s formulation still works more than 40 years later, even though his critics claimed it did not. Everyone has an ax to grind and you need to figure out what it is. Many times it is the search for truth, but sometimes it is just the preservation of the status quo.

Finally, seek the universal. The biggest breakthrough in biology occurred when Watson and Crick were able to show that DNA replication was at the heart of all living things. Now that we can sequence the genome, scientists realize that humans share most of their DNA not just with other primates, but with insects and virtually every other species. That is amazing! DNA is universal and so malleable that it can adapt to create a human eye or the compound eye of a fly.

Relative strength is part of the DNA of markets. Markets and asset classes everywhere exhibit momentum. Relative strength is universal and so malleable that it can be used to power stock selection or global tactical asset allocation. Relative strength makes no assumptions about the future-it simply adapts to what is. Darwin wrote, “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but rather the one most adaptable to change.” Relative strength is adaptive and adaptation is what ensures survival.

Relative strength has come full circle. After years of academic neglect and derision by fundamental analysts-and a blatant case of identity theft in renaming it “momentum”- relative strength as a return factor may be regaining its place at the table.