A new paper from Eugene Fama and Ken French is circulating, suggesting that active mutual fund managers don’t add value. Articles, like the one here at MarketWatch, have been appearing and the typical editorial slant is that you should just buy an index fund.

I have a bone to pick with this article and its conclusions, but certain things are not in dispute. Fama and French, in their article Luck versus Skill in the Cross Section of Mutual Fund Returns, look at the performance of domestic equity funds from 1984 to 2006. (You can find a summary of the paper here.) They discover that the funds, in aggregate, are worse than the market by 80 basis points per year-basically the amount of the fees and expenses. (After backing out fees and expenses, the funds are 10 basis points per year above the market.) After that, Fama and French run 10,000 simulations with alpha set to zero to see if the distribution of returns from actual fund managers is any different from the distribution of returns from the random simulations. They conclude it is not very different and suggest that any fund manager that outperforms is simply lucky.

Let me start my critique by pointing out that, based on their sample and their experimental design, their conclusions are probably correct. Existing mutual funds in aggregate pretty much own the market portfolio and underperform by the amount of fees and expenses. There clearly are some above-average mutual fund managers, but as Fama and French point out, it’s difficult to tell statistically from just performance data if they are good or simply lucky. Within a big sample of funds like they had, after all, a few are bound to have good performance just because the sample is so large.

This is quite a quandary for the individual investor, so let’s think about the realistic scenarios and their outcomes-in other words, let’s take actual investor behavior into account.

Scenario 1. Buy a mutual fund after its good performance is advertised somewhere and bail out when it has a bad year. Continue this behavior throughout your investment lifetime. According to Dalbar’s QAIB and other data, this is what actually happens most of the time. Not a good outcome-underperformance by a large margin, often 500 basis points or more annually.

Scenario 2. Buy a decent mutual fund and make the radical decision to leave it alone, come hell or high water. Do not be tempted by the blandishments of currently hot funds or panicked by underperformance in your fund when it inevitably happens. Close eyes and hold on for dear life. Continue your ostrich-with-its-head-in-the-sand routine throughout your investment lifetime. Your outcome, as Fama and French point out, will probably be market returns less the 80 basis point per year in fees. Your returns will probably be 400 basis points annually or more better than Scenario 1.

Scenario 3. Throw active management overboard entirely. Buy an S&P 500 index fund or a total market index fund and proceed as in Scenario 2. Your outcome might be 60-70 basis points per year better from reduced costs than the investor in Scenario 2. (Your cost is that you don’t get to brag at cocktail parties on the occasions when your actively managed fund has a good year.) On the other hand, you are no less likely to succumb to Scenario 1 than an actively managed mutual fund investor. Unfortunately, index mutual funds tend to show the same pattern of lagging returns due to investor behavior as actively managed funds.

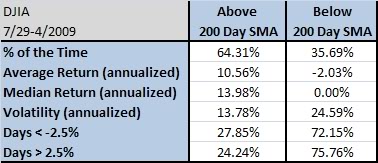

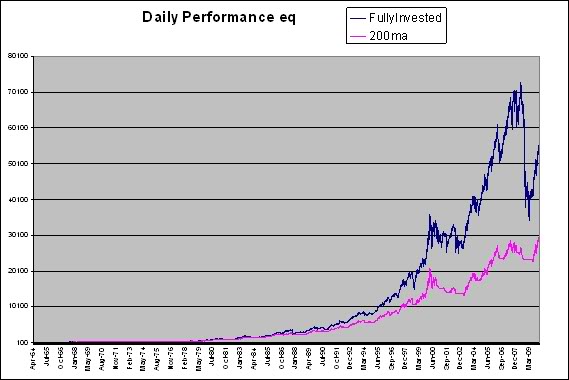

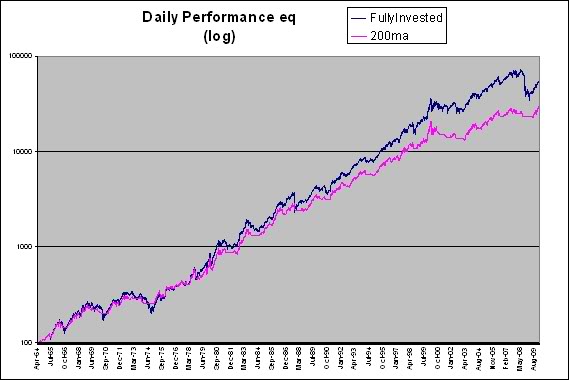

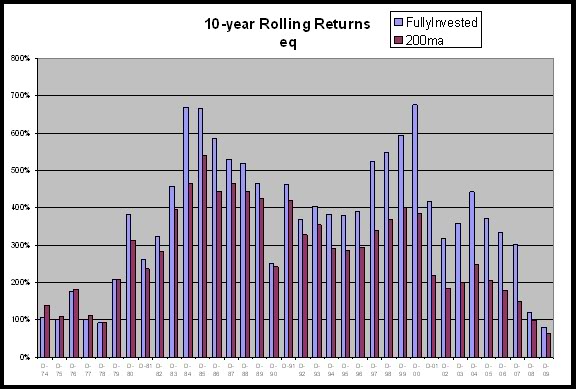

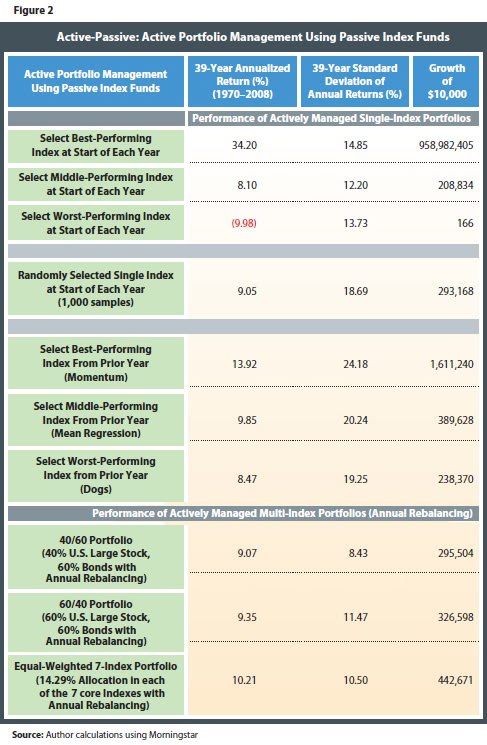

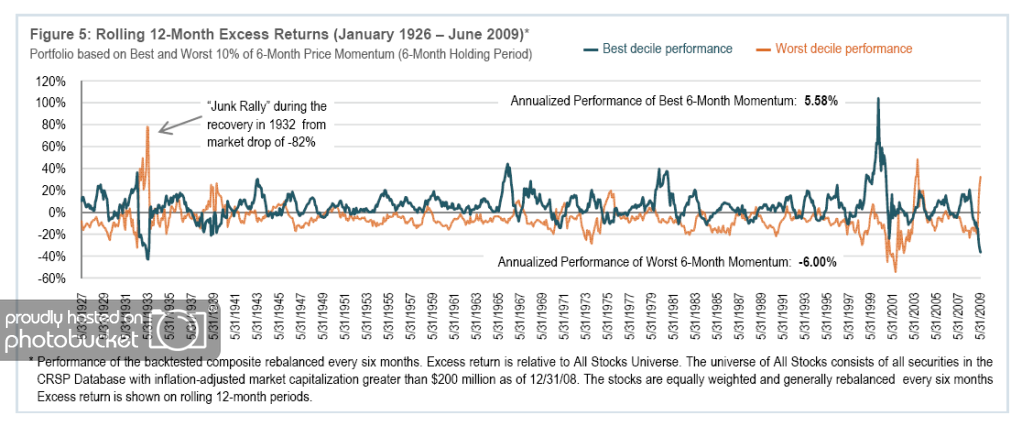

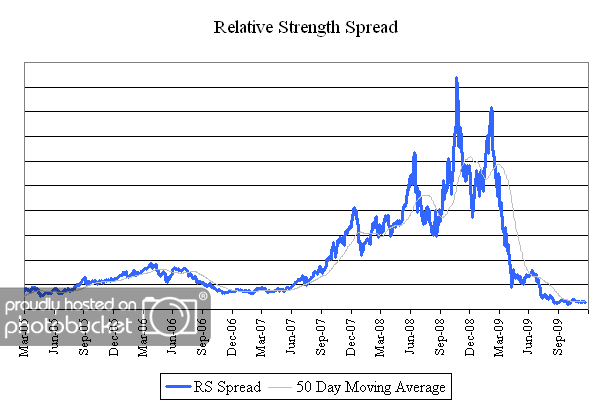

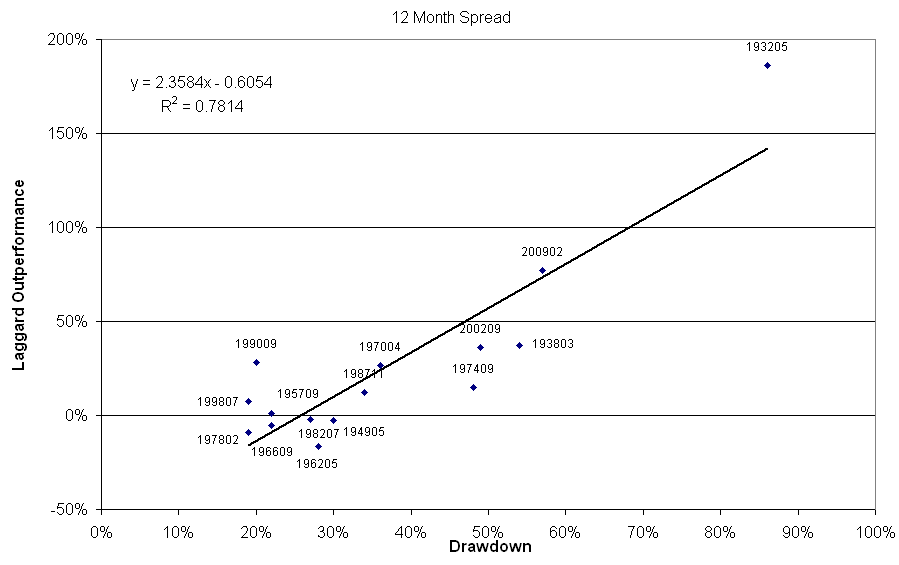

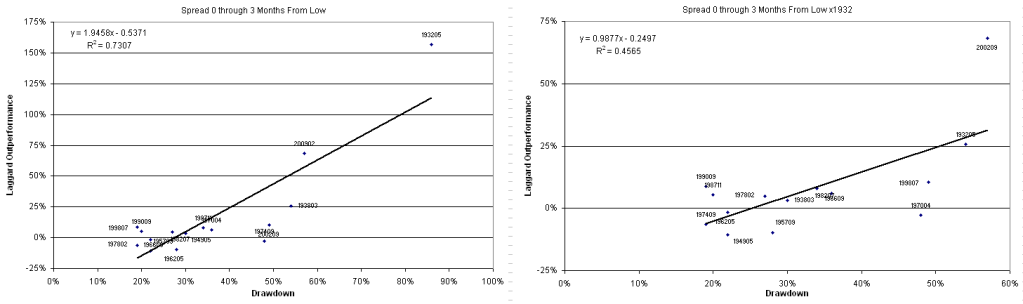

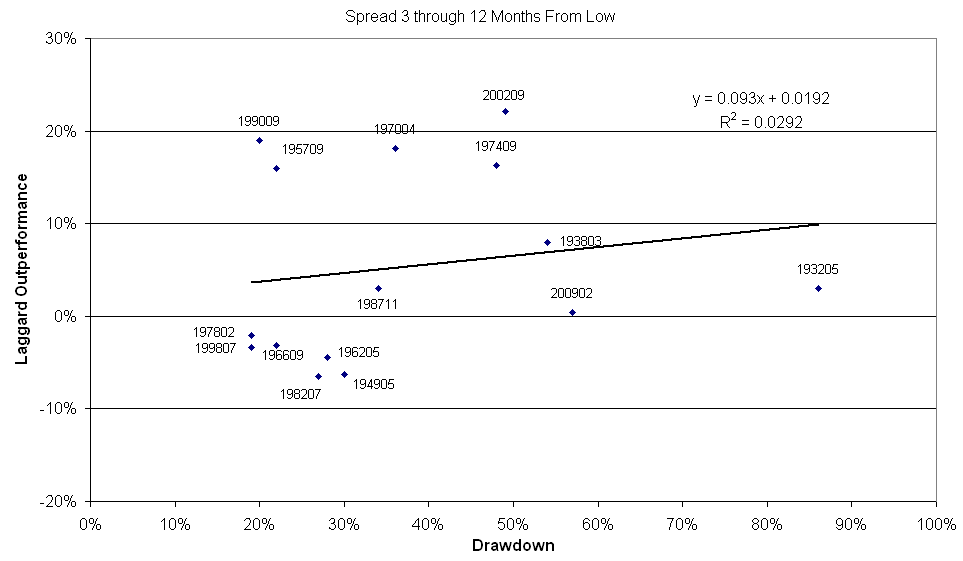

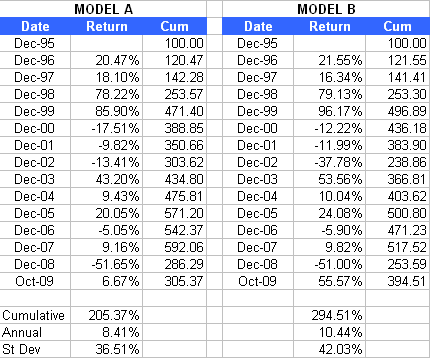

Scenario 4. Visit Ken French’s own website. Look for factors that are tested and that have outperformed consistently over time. Hint: relative strength. (Academics tend to call it ”momentum,” I suspect because it would be very deflating to have to admit that anything related to technical analysis actually works.) Find a manager that exposes a portfolio to the relative strength factor in a disciplined fashion over time. Buy it and pretend you are Rip Van Winkle. Continue this dolt-like behavior for your entire investment lifetime. Your outcome, according to Ken French’s own website, is likely to be market outperformance on the magnitude of 500 basis points per year or more. (You can link to an article showing a performance chart back to 1927 here, and the article also includes the link to Ken French’s database at Dartmouth University.)

I prefer Scenario 4, but maybe that’s just me. Since it is well-known even to Eugene Fama and Ken French that momentum has outperformed over time, what is their study really saying? It’s saying that essentially no one in the mutual fund industry is employing this approach. That’s more a problem with the mutual fund industry than it is with anything else. (Mutual fund firms are businesses and they have their reasons for running the business the way they do.) One option, I guess, is to throw up your hands and buy an index fund, but maybe it would make more sense to seek out the rare firms that are employing a disciplined relative strength approach and shoot for Scenario 4.

Their experimental design makes no sense to me. Although I am 6’5″, I can no longer dunk a basketball. I imagine that if I ran a sample of 10,000 random Americans and measured how close they could get to the rim, very few of them could dunk a basketball either. If I created a distribution of jumping ability, would I conclude that, because I had a large sample size, the 300 people would could dunk were just lucky? Since I know that dunking a basketball consistently is possible-just as Fama and French know that consistent outperformance is possible-does that really make any sense? If I want to increase my odds of finding a portfolio of people who could dunk, wouldn’t it make more sense to expose my portfolio to dunking-related factors-like, say, only recruiting people who were 18 to 25 years old and 6’8″ or taller? In the same fashion, if I am looking for portfolio outperformance, doesn’t it make a lot more sense to expose my portfolio to factors related to outperformance, like relative strength or deep value, rather than to conclude that managers who add value are just lucky? No investigation of possible sub-groups that were consistently following relative strength or deep value strategies was done, so it is impossible to tell. Fama and French are right, I think, in their assertion that plenty of luck is involved in year-to-year performance, but their overall conclusion is questionable.

In short, I think a questionable experimental design and possible sub-groups buried in the aggregate data (see this post for more information on tricks with aggregate data) make their conclusions rather suspect.