As the front end of the baby boomers hit retirement age, investing for income has become their mantra. Retirees are often sold terrible investments because of their known propensity to lunge at income the way a starving fish attacks a baited hook. But is investing for income desirable, or even possible? Let’s take a look at the income possibilities from bonds, stocks, and alternatives.

Bonds are boring and safe, and are usually the first place investors go for income-except that with current interest rates, there isn’t much income available. Most retirees can’t live on 2-year Treasury yields of 1.04%, and moving out to the 30-year Treasury at 4.72% brings with it a significant chance of getting hurt by inflation. Yields on junk bonds (euphemistically known as high-yield bonds) are higher, but that crosses over from investing for income to its less glamorous cousin, “reaching for yield.” Junk bonds might work for a while, as long as the economy is in recovery mode, but are probably not a long-term solution for a retiree. As the saying goes, “More money has been lost reaching for yield than at the point of a gun.”

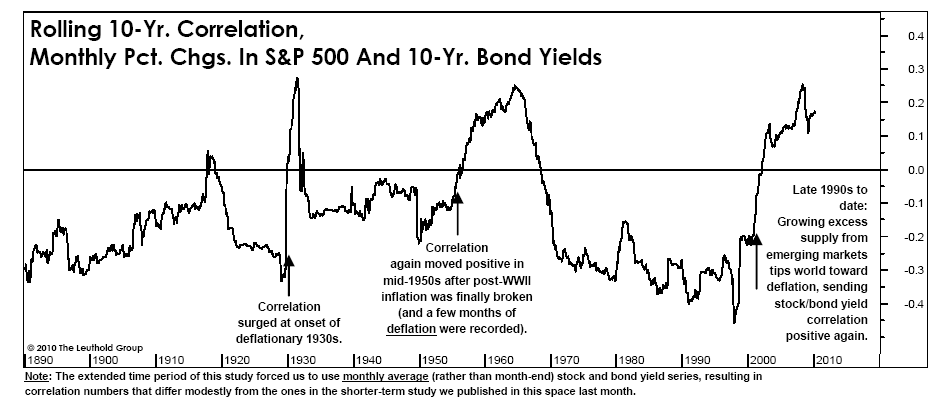

Many investors have looked to the stock market for dividend yield. Doug Short has a nice piece on the disappearing yields in stocks on his excellent site. The chart below is taken from his article. Stock prices have been rising, but dividend yields have been going the other direction.

Click to enlarge. Source: dshort.com

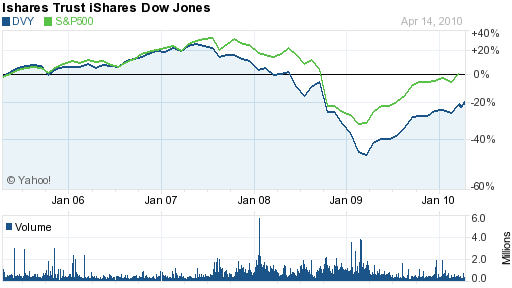

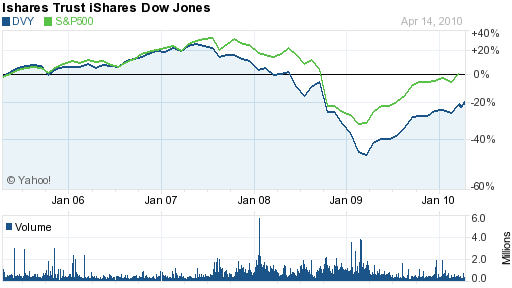

The traditional high-dividend sectors for investors were always banks, oil stocks, utilities, and REITs. When stock prices plunged in 2008, many banks eliminated or severely slashed their dividends. Some REITs had the same problem. Oil stocks and utilities don’t have nearly the dividend yields they used to. All of the dividend cuts and reductions caused the high-yielding equities to do worse than the general market. (See the chart below for a comparison of the S&P 500 to the Dow Jones Select Dividend Index ETF.)

Source: Yahoo! Finance

Alternatives range from MLPs (typically finite lives and unstable income streams) to all sorts of structured products. This morning someone sent me an offering flyer for a 12-year 8% CD, where the quarterly rate is based on the slope of the yield curve. 8% was the cap rate, but it could drop to 0% if the yield curve flattened out. I’m not sure Mrs. Jones is ready to speculate with derivatives.

All in all, it appears that the income investor has hit a rough patch and there seems to be no easy way out. I’m going to let you in on a secret that very few investors know: capital gains can be spent just as easily as dividends. Ok, that’s not really a secret at all, but many investors act like it is. They chase yield so they can spend the income, but really, total return is all that matters.

Segmentation, like the distinction investors often impose between income and principal, is a natural function of the mind. Many retirement planners have been using this human tendency to segment things by presenting a retirement income solution that consists of a number of buckets, a solution that is generally well-received by clients.

The first bucket is the liquidity bucket, where spending will be drawn from. The second bucket is the income bucket, which is typically put into some kind of fixed-income investment. The third bucket is the growth bucket. By segmenting the growth portion, the investor might be more willing to leave it alone as it gyrates with the market.

When there is a particularly good quarter or good year, the growth bucket can be trimmed back and the proceeds “deposited” into the liquidity bucket. Obviously, you could use any number of buckets depending on how finely you choose to segment the investment universe. The relative size and specific composition of each bucket would be determined by the client’s situation. Most often, all of this can be done within one account. The buckets are mental, but they help separate the investments and their specific purpose in the client’s mind.

When viewed in the context of buckets within a single account, it becomes quite apparent that total return is what counts. Investing for income may be a misnomer; investing for total return is the real deal.

Posted by Mike Moody

Posted by Mike Moody