It’s not often that a passive investor committed to Modern Portfolio Theory will help make our case for active management based on relative strength, but heck, we’ll take any help we can get.

In this guest article from Money Magazine, William Bernstein of Efficient Frontier Advisors discusses findings from a study by Dimensional Fund Advisors. The article gets to the thesis early:

It’s a little-known and depressing fact, but the majority of individual securities tend to post negative returns over the long run.

This, I think, is a ringing indictment of buy-and-really-hold investing. Often individuals assume that they can purchase shares of leading companies, shower them with benign neglect, and have the portfolio perform well. But, of course, today’s leader always turns into tomorrow’s laggard. The majority of stocks, given enough time, collectively lose money. Mr. Bernstein goes on to say,

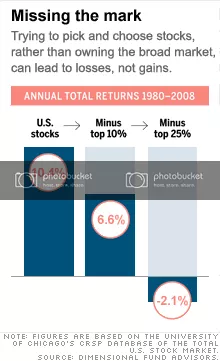

In fact, researchers at the investment management firm Dimensional Fund Advisors found that from 1980 to 2008, the top-performing 25% of stocks were responsible for all the gains in the broad market, as represented by the University of Chicago’s CRSP total equity market database.

As for the bottom 75% of stocks in the U.S. market, they collectively generated annual losses … over the past 29 years.

The following chart shows that if you miss the best 25% of stocks, you will end up losing more than 2% per year.

Source: Money Magazine and Dimensional Fund Advisors

The chart is offered as evidence of the futility of stock picking and the triumph of index investing. What it really reveals is this: index investing would be an abject failure if it weren’t for two things: 1) active management and/or 2) relative strength weighting. First, if indexes didn’t replace companies that went out of business or were no longer “representative,” they’d have a buy-and-hold portfolio that, by their own calculations, would lose money. Replacing losers (dead companies) with winners (live companies) is, in fact, an efficient casting out process used for active portfolio management. Second, index returns are helped immensely by increasing the weighting of the stocks that go up the most. This is actually a form of relative strength weighting, more commonly referred to by index providers as “capitalization weighting.” Emphasizing the winners at the expense of the losers also tends to help returns over time.

The alert reader will quickly discern that ”missing the best 25% of stocks” is another version of the “if you miss the 10 best days” argument. There’s one problem: while it may be impossible to pick out the 10 best days, there’s a ton of evidence to suggest that it is possible to select the strongest stocks using relative strength. Even efficient market theorists like Eugene Fama and Kenneth French have admitted that relative strength works.

Bernstein writes:

This may get you thinking: If a small list of securities accounts for the market’s long-term returns, why not avoid all the headaches and losses you’ve suffered recently by carefully choosing these superstocks?

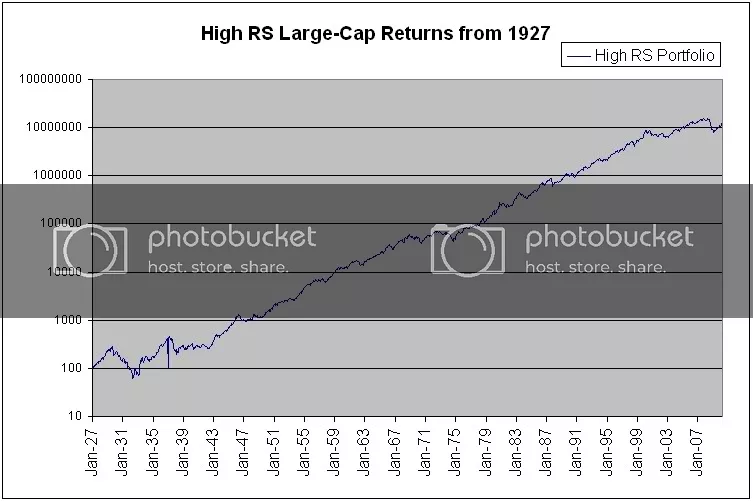

That’s exactly what I’m thinking! Why not, indeed! I’d rather own the superstocks. And I will even let Ken French pick the stocks. Instead of buying an index fund, I’m going to let Ken French buy the best recent performers and cast out the stocks that weaken each month. This chart comes from Dr. French’s own website and shows the equity curve for large-cap, high relative strength stocks since 1927.

As an investor, you have three basic options. You can buy-and-really-hold which will insure that most of the companies you buy will lose money over a long time frame. You can buy an index fund, which will tend to perform better than buy-and-really-hold due to the hidden active management process of casting out and/or through capitalization weighting. Or you can identify the strongest stocks and use both casting out and relative strength weighting to manage the portfolio. Option 3 has historically provided the best returns, but it will be volatile and will go through periods of drawdown. (Of course, Options 1 and 2 will also be volatile and will go through periods of drawdown!)

As a result, I see no reason not to prefer active management using a systematic relative strength process. It’s always interesting to me how investors with a passive approach can selectively pull out data that they then claim supports an indexing approach. [Note: a major part of the reason for the cognitive dissonance in Dimensional Fund Advisors' data has to do with the original research source. The finding that 25% of all stocks account for all of the market's gains came from a Blackstar Funds research paper, The Capitalism Distribution. Blackstar's own interpretation of the findings was that such a skewed distribution of returns supported a trend-following method focused on strong stocks--exactly opposite of what DFA suggests! We happen to agree with Blackstar.]

Posted by Mike Moody

Posted by Mike Moody