We repeat this to our investors often, so often I probably mumble it in my sleep. You can imagine, then, how excited I was to read this great article on risk and volatility by Christine Benz, the personal finance writer at Morningstar. The article makes so many outstanding points it’s hard to know where to start. I highly recommend that you read the whole thing more than once.

Ms. Benz starts with the “risk tolerance” section of the typical consulting group questionnaire. They generally ask at what level of loss an investor would become concerned and pull the plug. (In my experience, many clients are not very insightful; every advisor has seen at least one questionnaire of a self-reported aggressive investor with a 5% loss tolerance!) In truth, these questionnaires are next to worthless, and she points out why:

Unfortunately, many risk questionnaires aren’t all that productive. For starters, most investors are poor judges of their own risk tolerance, feeling more risk-resilient when the market is sailing along and becoming more risk-averse after periods of sustained market losses.

Moreover, such questionnaires send the incorrect message that it’s OK to inject your own emotion into the investment process, thereby upending what might have been a carefully laid investment plan.

But perhaps most important, focusing on an investor’s response to short-term losses inappropriately confuses risk and volatility. Understanding the difference between the two-and focusing on the former and not the latter-is a key way to make sure your reach your financial goals.

There are three different issues she addresses here, so let’s look at each of them in turn.

1) You’re a crummy judge of your own risk tolerance. We all are. That’s because our money is personal to us. One of my psychologist clients once exclaimed, “Money is my most neurotic asset!” It’s much easier to take an outside view and look at it with some psychological distance. An experienced advisor is more likely to be able to gauge your risk tolerance correctly than you are. There are also good resources like Finametrica for learning more about psychologically appropriate levels of portfolio risk. But Ms. Benz really gets to the heart of things: your risk tolerance will change depending on your emotions! That’s something no advisor can calibrate exactly, nor are you likely to guess how powerfully the swell of fear will hit you after a particularly heinous quarterly statement.

2) It’s not okay to panic. As Ms. Benz points out, discussing loss tolerance in this fashion implies that it is ok to bail out emotionally at some point. If you have losses that are uncomfortable, perhaps you need to revisit your overall plan, but it’s unlikely that major modifications are needed if you were thoughtful when you put it together in the first place. Markets, and strategies, go through tough periods and it’s important to be able to persevere.

3) At the height of emotion, volatility and risk get confused. Volatility is just a measurement of how much your investments are whipping around at the moment. Risk isn’t the same thing. Ms. Benz clarifies the difference:

…volatility usually refers to price fluctuations in a security, portfolio, or market segment during a fairly short time period-a day, a month, a year. Such fluctuations are inevitable once you venture beyond certificates of deposit, money market funds, or your passbook savings account. If you’re not selling anytime soon, volatility isn’t a problem and can even be your friend, enabling you to buy more of a security when it’s at a low ebb.

The most intuitive definition of risk, by contrast, is the chance that you won’t be able to meet your financial goals and obligations or that you’ll have to recalibrate your goals because your investment kitty come up short.

Through that lens, risk should be the real worry for investors; volatility, not so much. A real risk? Having to move in with your kids because you don’t have enough money to live on your own. Volatility? Noise on the evening news, and maybe a frosty cocktail on the night the market drops 300 points.

This is one of the best descriptions of risk I’ve ever read, one that puts opportunity cost front and center. Risk isn’t your portfolio moving around; that’s just volatility—noise, really. Risk is eating Alpo in retirement, or as she mentions, being forced to move in with your kids.

Source: Purina

Risk is the very real possibility of having a severe investment shortfall if you avoid volatility like the plague. Low volatility investments earn low returns (or worse if they are Ponzi achemes).

The challenge of every individual investor, hopefully with help from a qualified financial advisor, is how to balance volatility and return-while keeping risk from sneaking up and biting you you-know-where. Ms. Benz has some thoughts on this as well:

So how can investors focus on risk while putting volatility in its place? The first step is to know that volatility is inevitable, and if you have a long enough time horizon, you’ll be able to harness it for your own benefit. Using a dollar-cost averaging program-buying shares at regular intervals, as in a 401(k) plan-can help ensure that you’re buying securities in a variety of market environments, whether it feels good or not.

Diversifying your portfolio among different asset classes and investment styles can also go a long way toward muting the volatility of an investment that’s volatile on a stand-alone basis. That can make your portfolio less volatile and easier to live with.

Again, she makes several very cogent points, so let’s deal with them one by one.

1) Volatility is inevitable. Deal with it. Preferably by constructing your portfolio thoughtfully in the first place.

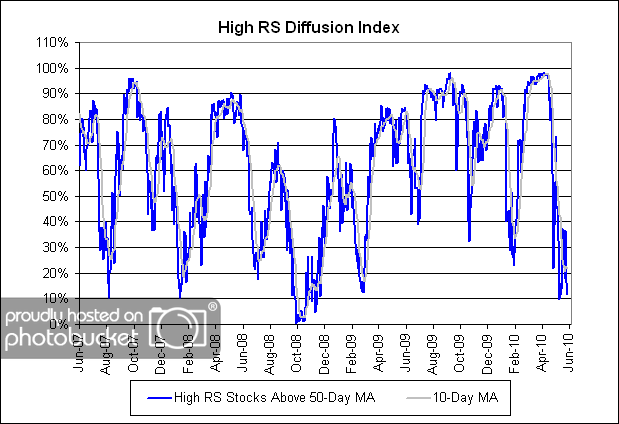

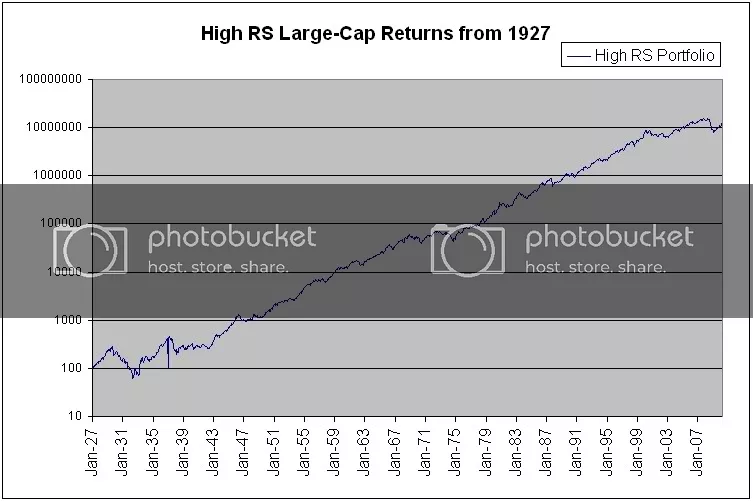

2) Better yet, volatility can be your ally. Buy on dips. (Easy to say, harder to do.) In truth, high-return, high-volatility strategies can be tremendous wealth builders because the long-term returns are good and you get plenty of opportunities to add money during the dips. Toward that end, we publish a High RS Diffusion Index each week to help identify those dips in our particular strategy.

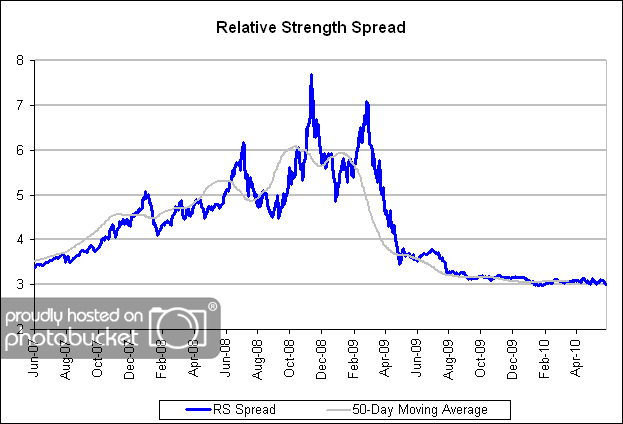

3) Diversify appropriately. We believe it’s often more fruitful to mix strategies as opposed to asset classes. For example, relative strength strategies tend to work very well when blended with deep value strategies.

Ms. Benz lays out the real definition of risk: failing to accomplish your goals.

It also helps to articulate your real risks: your financial goals and the possibility of falling short of them. For most of us, a comfortable retirement is a key goal; the corresponding risk is that we’ll come up short and not have enough money to live the lifestyle we’d like to live.

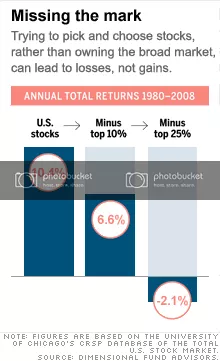

Clearly, the biggest risk for most investors is their own behavior. They avoid volatility rather than embracing it. Instead of buying on dips and being patient with proven strategies, they sell during pullbacks and buy only after an extended period of good performance. When you start to conceptualize risk as shortfall risk, you can also see that another of your big risks is not saving enough in the first place. At the risk of sounding like my mom, if you don’t have any money, no investment advisor is going to be able to help you retire. Savings, too, is behavior that can be modified.

What can be done to help clients embrace volatility, or at least deal constructively with it? Are there any ”nudges” that can be applied in order to increase their patience and their overall good investment behavior? Ms. Benz makes a suggestion in this regard:

Many financial advisors have begun to embrace the concept of creating separate “buckets” of a portfolio-and in particular, a bucket for any cash the investor expects to need within the next couple of years. By carving out a piece of your portfolio that’s sacrosanct and not subject to volatility or risk, you can more readily tolerate fluctuations in the long-term component of your portfolio.

Sure, it’s a cheap psychological trick that plays to the mind’s natural tendency to segment things-but if it helps, why not? We’ve discussed in the past that a portfolio carved into buckets is functionally equivalent to a balanced or diversified portfolio with the same asset allocation, but if it helps clients behave better then it’s worth trying.

Whether you are an advisor or an individual investor, educating yourself about key concepts like the difference between volatility and risk will pay large dividends down the road.

Posted by Mike Moody

Posted by Mike Moody