Markets have been extremely volatile over the last couple of months. Volatile markets are very difficult to navigate. It is very easy to make mistakes, and when a mistake is made it is magnified by the volatility. From a relative strength standpoint, there are things you can do to help ease the pain of all of these large, unpredictable market moves. But judging by all the client calls we have taken over the years-almost always when volatility was high-the steps needed to make a relative strength model perform well are most definitely not what most investors would think!

Before we look at relative strength specifically, let’s take a step back and look at different investment strategies on a very broad basis. There are really two types of strategies: trend continuation and mean reversion. A trend continuation strategy buys a security and assumes it will keep moving in the same direction. A mean reversion (or value) strategy buys a security and assumes it will reverse course and come closer to a more “normal” state. Both strategies work over time if implemented correctly, but volatility affects them in different ways. Mean reversion strategies tend to thrive in high volatility markets, as those types of markets create larger mispricings for value investors to exploit.

When we construct systematic relative strength models, we have always preferred to use longer-term rather than shorter-term signals. This decision was made entirely on the basis of data—by testing many models over a lot of different types of markets. Judging by all the questions we get during periods of high volatility, I would guess that using a longer-term signal when the market is volatile strikes most investors as counter-intuitive. In my years at Dorsey Wright, I can’t remember talking to a single client or advisor that told me when markets get really volatile they look to slow things down!

During volatile markets, generally we hear the opposite view-everyone wants to speed up their process. Speeding up the process can take many forms. It might mean using a smaller box size on a point and figure chart, or using a 3-month look back instead of a 12-month look back when formulating your rankings. It might be as simple as rebalancing the portfolio more often, or tightening your stops. Whatever the case, most investors are of the opinion that being more proactive in these types of markets makes performance better.

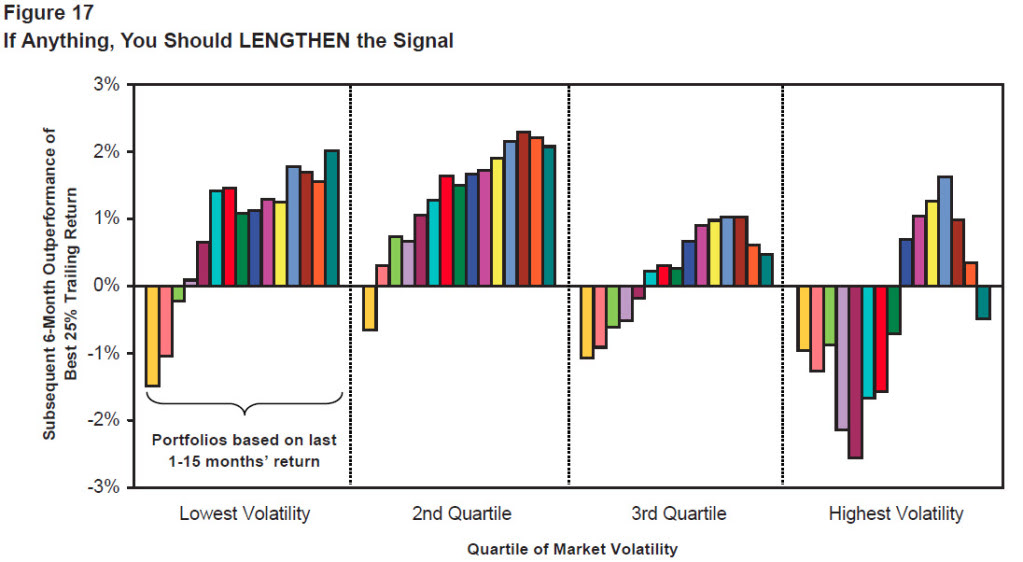

Their gut response, however, is contradicted by the data. As I mentioned before, our testing has shown that slowing down the process actually works better in volatile markets. And we aren’t the only ones who have found that to be the case! GMO published a whitepaper in March 2010 that discussed momentum investing (the paper can be found here). Figure 17 on page 11 specifically addresses what happens to relative strength models during different states of market volatility.

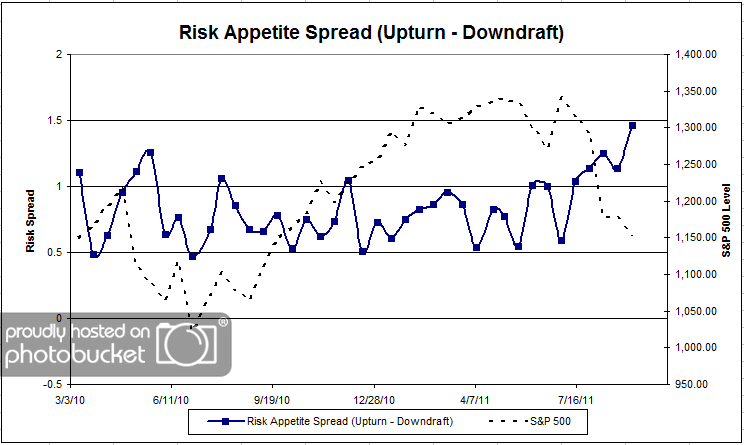

(Click Image To Enlarge. Source: GMO Whitepaper, Sept. 2010)

The chart clearly shows how shortening your look back period decreases performance in volatile markets. The 6-12 month time horizon has historically been the optimal time frame for formulating a momentum model. But when the market gets very volatile, the best returns come from moving all the way out to 12 months, not shortening your window to make your model more sensitive.

Psychologically, it is extremely difficult to lengthen your time horizon in volatile markets. Every instinct you have will tell you to respond more quickly in order to get out of what isn’t working and into something better. But the data says you shouldn’t shorten your window, and conceptually this makes sense. Volatile markets tend to be better for mean reversion strategies. But for a relative strength strategy, volatile markets also create many whipsaws. When thinking about how volatility interacts with relative strength, it makes sense to lengthen your time horizon. Hopping on every short term trend is problematic if the trends are constantly reversing! All the volatility creates noise, and the only way to cancel out the noise is to use more (not less) data. You can’t react to all the short-term swings because the mean reversion is so violent in volatile markets. It doesn’t make any sense to get on trends more rapidly when you are going through a period that is not optimal for a trend following strategy.

We use a data-driven process to construct models. We have found that using a relatively longer time horizon, while uncomfortable, ultimately leads to better performance over time. Outside studies show the same thing. If the data showed that reacting more quickly to short-term swings in volatile markets was superior we would advocate doing exactly that!

As is often the case in the investing world, this seems to be another situation where doing the most uncomfortable thing actually leads to better performance over time. Good investing is an uphill run against human nature. Of course, it stands to reason that that’s the way things usually are. If it were comfortable, everyone would do it and investors would find their excess return quickly arbitraged away.