Man versus machine, art versus science, intuition versus logic—all of these are ways of expressing what we often think of as contradictory approaches to problem solving. Should we be guided more by data and precedent, or is it more important to allow for the human element? Is it critical to be able to step aside and say, with the benefit of our judgment, “maybe this time really is different?”

The Harvard Business Review recently took on this topic and a few of their points were quite provocative.

A huge body of research has clarified much about how intuition works, and how it doesn’t. Here’s some of what we’ve learned:

- It takes a long time to build good intuition. Chess players, for example, need 10 years of dedicated study and competition to assemble a sufficient mental repertoire of board patterns.

- Intuition only works well in specific environments, ones that provide a person with good cues and rapid feedback . Cues are accurate indications about what’s going to happen next. They exist in poker and firefighting, but not in, say, stock markets. Despite what chartists think, it’s impossible to build good intuition about future market moves because no publicly available information provides good cues about later stock movements. [Needless to say, I don't agree with his assessment of stock charts!] Feedback from the environment is information about what worked and what didn’t. It exists in neonatal ICUs because babies stay there for a while. It’s hard, though, to build medical intuition about conditions that change after the patient has left the care environment, since there’s no feedback loop.

- We apply intuition inconsistently. Even experts are inconsistent. One study determined what criteria clinical psychologists used to diagnose their patients, and then created simple models based on these criteria. Then, the researchers presented the doctors with new patients to diagnose and also diagnosed those new patients with their models. The models did a better job diagnosing the new cases than did the humans whose knowledge was used to build them. The best explanation for this is that people applied what they knew inconsistently — their intuition varied. Models, though, don’t have intuition.

- We can’t know or tell where our ideas come from. There’s no way for even an experienced person to know if a spontaneous idea is the result of legitimate expert intuition or of a pernicious bias. In other words, we have lousy intuition about our intuition.

- It’s easy to make bad judgments quickly. We have many biases that lead us astray when making assessments. Here’s just one example. If I ask a group of people “Is the average price of German cars more or less than $100,000?” and then ask them to estimate the average price of German cars, they’ll “anchor” around BMWs and other high-end makes when estimating. If I ask a parallel group the same two questions but say “more or less than $30,000″ instead, they’ll anchor around VWs and give a much lower estimate. How much lower? About $35,000 on average, or half the difference in the two anchor prices. How information is presented affects what we think.

We’ve written before about how long it takes to become world-class. Most studies show that it takes about ten years to become an expert if you apply yourself diligently. Obviously, the “intuition” of an expert is much better than the intuition of a neophyte. If you think about that for a minute, it’s pretty clear that intuition is really just judgment in disguise. The expert is better than the novice simply because they have a bigger knowledge base and more experience.

Really, the art versus science debate is over and the machines have won it going away. Nowhere is this more apparent than in chess. Chess is an incredibly complex mental activity. Humans study with top trainers for a decade to achieve excellence. There is no question that training and practice can cause a player to improve hugely, but it is still no contest. As processing power and programming experience has become more widespread, a $50 CD-ROM off-the-shelf piece of software can defeat the best players in the world in a match without much problem. Most of the world’s top grandmasters now use chess software to train with and to check their ideas. (In fact, so do average players since the software is so cheap and ubiquitous.)

How did we get to this state of affairs? Well, the software now incorporates the experience and judgment of many top players. Their combined knowledge is much more than any one person can absorb in a lifetime. In addition, the processing speed of a standard desktop computer is now so fast that no human can keep it with it. It doesn’t get tired, upset, nervous, or bored. Basically, you have the best of both worlds—lifetimes of human talent and experience applied with relentless discipline.

A 2000 paper on clinical versus mechanical prediction by Grove, Zald, Lebow, Snitz, & Nelson had the following abstract:

>The process of making judgments and decisions requires a method for combining data. To compare the accuracy of clinical and mechanical (formal, statistical) data-combination techniques, we performed a meta-analysis on studies of human health and behavior. On average, mechanical-prediction techniques were about 10% more accurate than clinical predictions. Depending on the specific analysis, mechanical prediction substantially outperformed clinical prediction in 33%–47% of studies examined. Although clinical predictions were often as accurate as mechanical predictions, in only a few studies (6%–16%) were they substantially more accurate. Superiority for mechanical-prediction techniques was consistent, regardless of the judgment task, type of judges, judges’ amounts of experience, or the types of data being combined. Clinical predictions performed relatively less well when predictors included clinical interview data. These data indicate that mechanical predictions of human behaviors are equal or superior to clinical prediction methods for a wide range of circumstances.

That’s a 33-47% win rate for the scientists and a 6-16% win rate for the artists, and that was ten years ago. That’s not really very surprising. Science is what has allowed us to develop large-scale agriculture, industrialize, and build a modern society. Science and technology are not without their problems, but if the artists have stayed in charge we might still be living in caves, although no doubt we would have some pretty awesome cave paintings.

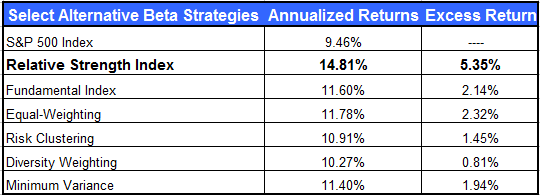

This is the thought process behind our Systematic Relative Strength accounts. We were able to codify our own best judgment, include lifetimes of other experience from investors we interviewed or relative strength studies that we examined, and have it all run in a disciplined fashion. We chose relative strength because it was the best-performing factor and also because, since it is relative, it is adaptive. There is always cooperation between man and machine in our process, but moving more toward data-driven decisions is indeed the future of decision making.

—-this article originally appeared 1/15/2010. Our thought process hasn’t changed—we still believe that a systematic, adaptive investment process is the way to go.