This article is about history that is still being written, and about a simple way to create a powerful, sustainable economy. It is about Lee Kuan Yew and the Singapore Central Provident Fund. Never heard of it? Neither had I, until I happened upon a story about it in the book Animal Spirits by George Akerlof and Robert Schiller. I was fascinated and dug in to do a little further research. The best thing about this story is that it is true—and therefore it is repeatable. It has critical lessons for the United States, if we want to remain a world power. And it is something we can easily do, if we make the choice to do it.

Most debates about the sluggish economy are conducted along Keynesian lines and argue that spending needs to be stimulated. If people would just spend more, the economy would grow. After all, the reasoning goes, consumer spending is 2/3 of the economy. This line of thinking led to citizens actually being sent spending money—stimulus checks—in the mail! The effect was pretty much what you would expect if you thought about it for more than fifteen minutes: minimal and temporary. Giving someone money does not create prosperity—note the effects of sudden money on lottery winners.

What we have is not a spending problem, but a savings problem. Savings is what creates dynamic economic growth. Exhibit 1 in my case for the power of savings is Singapore. Singapore became quasi-independent in 1955, after being a British possession since the 1820s (although it was occupied by the Japanese during World War II). For a period of time, it was also part of Malaysia, but became fully independent in 1965. Lee Kuan Yew had some training at the London School of Economics and took classical economists like Adam Smith seriously. Adam Smith emphasized the capital accumulation that comes from savings. With no natural resources whatsoever, except its people and their work ethic, Singapore resolved to save its way out of poverty.

Singapore Skyline

Source: www.commons.wikimedia.org

Lee Kuan Yew started the Singapore Central Provident Fund in 1955 as a way for citizens to save for retirement. It has since been extended to include savings programs for housing and healthcare. According to Akerlof and Schiller:

Initially it required employees and employers each to contribute 5% of employees wage income to the fund, but then contribution rates were rapidly increased. They were steadily raised until 1983, when employer and employee were required to give 25% each (a total of 50%!). The contribution rates follow a complicated schedule, but even today high-wage employees age 25-50 pay 34.5% and their employers pay 20%. The system has not been “pay-as-you-go,” and the sums collected have really been invested. Largely because of the CPF, the gross national savings rate of Singapore has been in the vicinity of 50% for decades.

I put the important part in bold. This is completely unlike our Social Security system, where the employee and employer payroll contributions are deducted, but then spent immediately. As a result, in the US there is no actual surplus capital, only net debt which is an IOU on future generations. Singapore already has essentially privatized their Social Security system. Far from leading to fiscal disaster as some claim, the huge pool of enforced savings has not only secured the retirements of Singaporeans, it has allowed an enormous amount of capital investment.

Disciplined savings as a nation over a 50-year period literally transformed Singapore from a poor trading outpost that was kicked out of the Malaysian union to one of the wealthiest nations in the world. According to the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report:

Household wealth in Singapore grew steadily and vigorously during the past decade, rising from USD 105,000 at the outset to more than USD 250,000 at the end. Most was due to domestic growth and asset price increases rather than favorable exchange rate movements. As a consequence, Singapore now ranks fourth in the world in terms of average personal wealth.

Wealth in Singapore is double the average wealth level in Taiwan and 20 times higher than in a neighbor like Indonesia—not to mention higher than in the US. Now, I suppose it is not entirely surprising that a high savings rate leads to wealth. What is more interesting, I think, is what it did to the Singaporean economy. What grew out of the immense savings was a capital investment boom unlike anything ever seen. And, the capital investment was not made with borrowed money, robbed from Peter today to pay Paul tomorrow, but was based on actual savings. Thus, the growth was sustainable. Coupled with the power of compounding, the results have been astonishing.

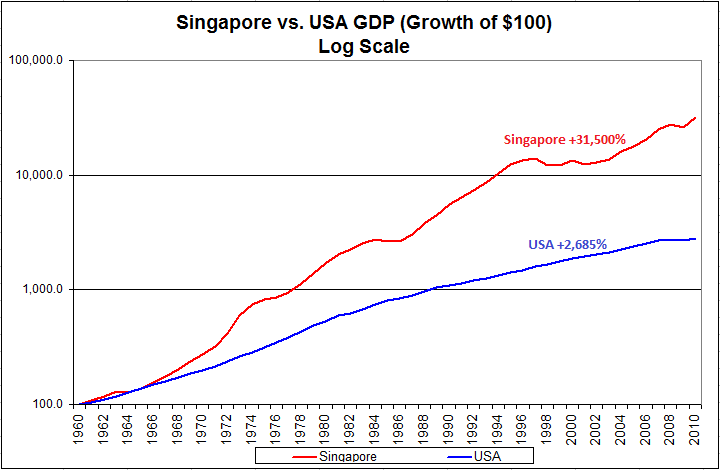

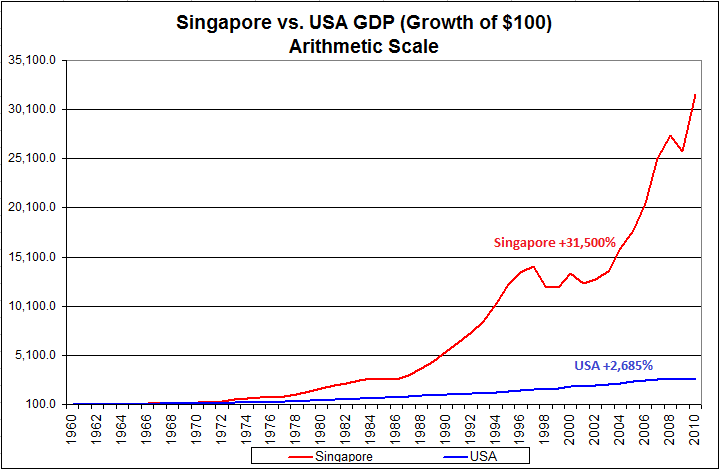

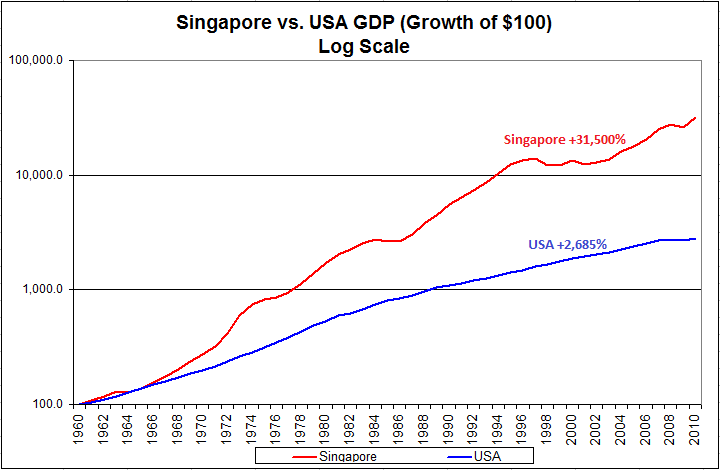

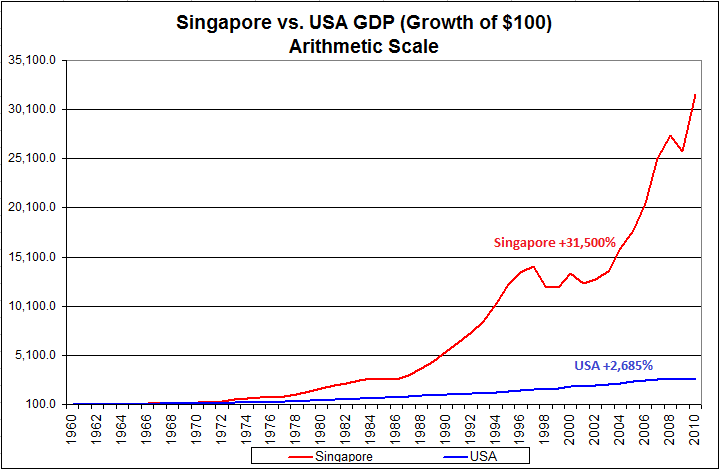

The able J.P. Lee did a little digging around for me and put together this graphic on the comparative GDP growth rates of the US and Singapore over the last 50 years. Shocking isn’t it?

Click to enlarge. Source: St. Louis Fed; Dept of Statistics, Government of Singapore

The graph on the top is a logarithmic scale which shows how much more rapid the economic growth in Singapore has been. The magnitude of the compounded difference, though, isn’t really apparent until you take a look at the arithmetic chart below it! GDP growth in the US over the last fifty years has been a robust 6.8%, but it has been dwarfed by the growth rate in Singapore, which has averaged a stunning 12.2%! (If we could get even a fraction of this additional growth by privatizing Social Security, sign me up.)

Can you imagine what a national savings program could accomplish in the US? We have many economic advantages already, ranging from an excellent university system, a diversified economy, and abundant natural resources to an outstanding record of technological innovation. What we lack is savings. Intelligent incentives to save and invest, coupled with Social Security payroll deductions that are actually invested in accounts for the participants could have a mind-boggling impact down the road.

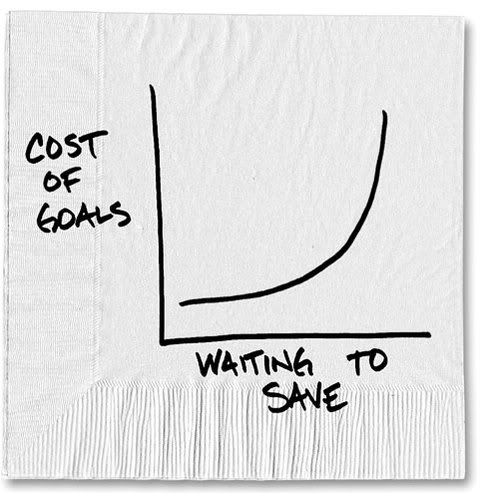

Personal savings is something quite different from government savings or spending. The US government seems addicted to deficit spending, but as a citizen you can’t do anything about that directly. On the other hand, your level of personal savings in entirely under your control. Like Singapore, most individuals have the ability to compound their savings for fifty years. Even if the US never adopts an intelligent enforced savings plan, there is nothing to stop you from doing it yourself.