Jason Zweig has written one of the best personal finance columns for years, The Intelligent Investor for the Wall Street Journal. Today he topped it with a piece that describes his vision of personal finance writing. He describes his job as saving investors from themselves. It is a must read, but I’ll give you a couple of excerpts here.

I was once asked, at a journalism conference, how I defined my job. I said: My job is to write the exact same thing between 50 and 100 times a year in such a way that neither my editors nor my readers will ever think I am repeating myself.

That’s because good advice rarely changes, while markets change constantly. The temptation to pander is almost irresistible. And while people need good advice, what they want is advice that sounds good.

The advice that sounds the best in the short run is always the most dangerous in the long run. Everyone wants the secret, the key, the roadmap to the primrose path that leads to El Dorado: the magical low-risk, high-return investment that can double your money in no time. Everyone wants to chase the returns of whatever has been hottest and to shun whatever has gone cold. Most financial journalism, like most of Wall Street itself, is dedicated to a basic principle of marketing: When the ducks quack, feed ‘em.

In practice, for most of the media, that requires telling people to buy Internet stocks in 1999 and early 2000; explaining, in 2005 and 2006, how to “flip” houses; in 2008 and 2009, it meant telling people to dump their stocks and even to buy “leveraged inverse” exchange-traded funds that made explosively risky bets against stocks; and ever since 2008, it has meant touting bonds and the “safety trade” like high-dividend-paying stocks and so-called minimum-volatility stocks.

It’s no wonder that, as brilliant research by the psychologist Paul Andreassen showed many years ago, people who receive frequent news updates on their investments earn lower returns than those who get no news. It’s also no wonder that the media has ignored those findings. Not many people care to admit that they spend their careers being part of the problem instead of trying to be part of the solution.

My job, as I see it, is to learn from other people’s mistakes and from my own. Above all, it means trying to save people from themselves. As the founder of security analysis, Benjamin Graham, wrote in The Intelligent Investor in 1949: “The investor’s chief problem – and even his worst enemy – is likely to be himself.”

……..

From financial history and from my own experience, I long ago concluded that regression to the mean is the most powerful law in financial physics: Periods of above-average performance are inevitably followed by below-average returns, and bad times inevitably set the stage for surprisingly good performance.

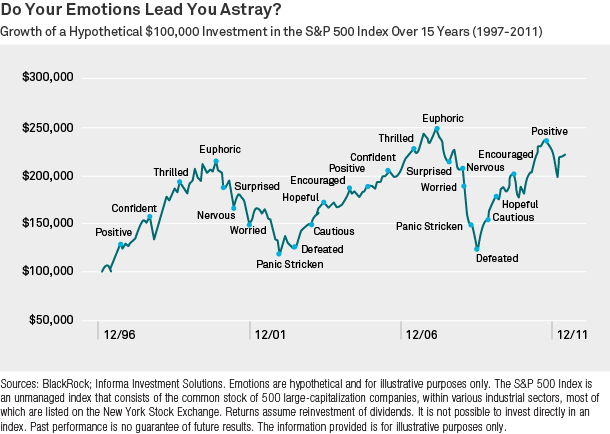

But humans perceive reality in short bursts and streaks, making a long-term perspective almost impossible to sustain – and making most people prone to believing that every blip is the beginning of a durable opportunity.

……..

But this time is never different. History always rhymes. Human nature never changes. You should always become more skeptical of any investment that has recently soared in price, and you should always become more enthusiastic about any asset that has recently fallen in price. That’s what it means to be an investor.

Simply brilliant. Unless you write a lot, it seems deceptively easy to write this well and clearly. It is not. More important, his message that many investment problems are actually investor behavior problems is very true—and has been true forever.

To me, one of the chief advantages of technical analysis is that it recognizes that human nature never changes and that, as a result, behavior patterns recur again and again. Investors predictably panic when market indicators get deeply oversold, just when they should consider buying. Investors predictably want to pile into a stock that has been a huge long-term winner when it breaks a long-term uptrend line—because “it’s a bargain”—just when they might want to think about selling. Responding deliberately at these junctures doesn’t usually require the harrowing activity level that CNBC commentators seem to believe is necessary, but can be quite effective nonetheless. Technical indicators and sentiment surveys often show these turning points very clearly, but as Mr. Zweig describes elsewhere in the article, the financial universe is arranged to deceive us—or at least to tempt us to deceive ourselves.

Investing is one of the many fields where less really is more.