From AdvisorOne, yet another article about how much investors hate the market these days:

Despite strong U.S. equity market returns in early 2012 that sent the Dow back above 13,000 by the end of February, indications are that many Americans remain investment spectators, reluctant to participate in the equity market rally, a Franklin Templeton global poll has found.

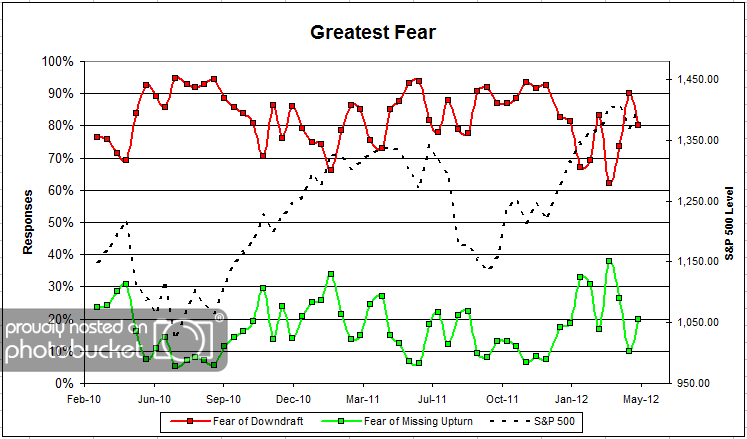

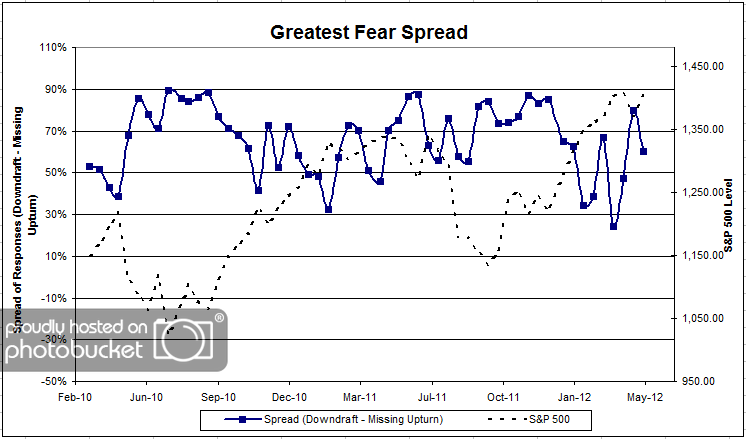

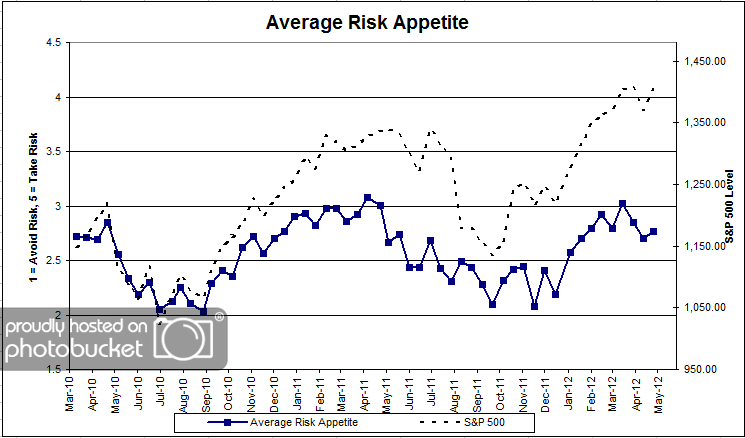

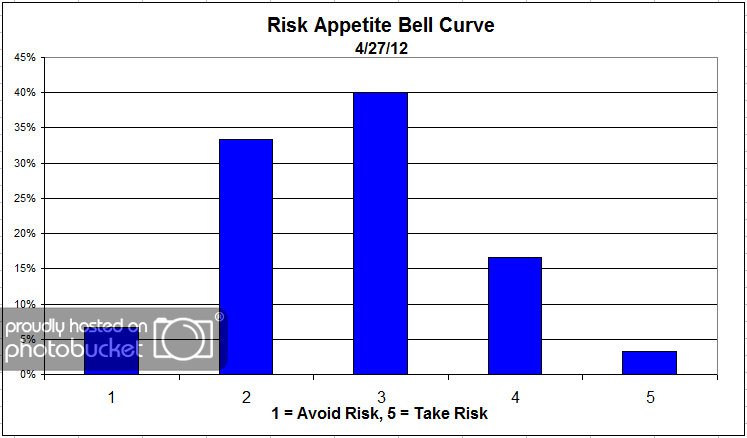

Investor skepticism appears to be tied to the extreme volatility witnessed in 2011, in which the Dow Jones Industrial Average had 104 days of triple-digit swings-representing a significant portion of the 252 total trading days last year. Indeed, when asked about the importance of various market scenarios when deciding to purchase an equity investment, market stability was most frequently identified by U.S. respondents as an important factor.

“The market volatility that has persisted since 2008 is keeping many investors on the sidelines, and their ability to view positive equity market performance constructively has been thwarted by the market ups and downs that are at odds with the stability they are seeking,” John Greer, executive vice president of corporate marketing and advertising at Franklin Templeton Investments, said in a statement. “But the reality is that investors who have been waiting for ‘the right time’ to get back into the equity market have been missing out on the market rally we’ve witnessed over the past few years.”

This is sadly typical of retail investors. Volatility tends to be greatest at market bottoms, and volatility tends to be what investors most avoid. As a result, investors often avoid returns as well!

This period strikes me as psychologically reminiscent of the late 1970s, when Business Week famously published a cover announcing the death of equities. Consider what investors had been through: in the late 1960s, the speculative names had gotten torched. By 1973-74 even the bluest of the blue chips had gotten ripped. By the late 1970s, 20% annual corrections were the norm. The economy was a mess and investors simply opted out. The Business Week cover just reflected the spirit of the time.

The late 1970s are not so different from now. The speculative names collapsed in 2000-2002, followed by a bear market in 2008-2009 that got everything. The last couple of summers have been punctuated by scary 15-20% corrections. The economy is still a mess. Psychologically, investors are in the same spot they were when the original cover came out. Based on fund flows, “anything but stocks” seems to be the battle cry.

Yet, consider how things unfolded subsequently. Only a few years later both the market and the economy were booming. (High relative strength stocks began to perform very well several years ahead of the 1982 bottom, by the way.) The Business Week cover is now famous as a contrary indicator. It wouldn’t shock me if the current investor disdain for stocks has a similar outcome down the road.