One of the reasons that we like to use relative strength as a return factor is its precision, its lack of assumptions, and its universality–basically its ability to rank even very disparate assets.

Although value managers often discuss assets or stocks that are undervalued, there is little agreement on how value works. Take, for example, a Bloomberg story from today, entitled U.S. Stocks Cheapest Since 1990 on Analyst Estimates. With a title like that, you would expect an article that discusses how cheap stocks are relative to earnings. And, indeed, the article cites such a source:

“The stock market is incredibly inexpensive,” said Kevin Rendino, who manages $11 billion in Plainsboro, New Jersey, for BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager. “I don’t know how the bears can argue against how well corporations are doing.”

Not only are stocks cheap, but analysts seem reluctant to buy in, something that strikes me, from a contrary opinion point of view, as unabashedly positive.

While analysts are raising estimates, they’re not boosting investment ratings. Companies ranked “buy” make up 30 percent of all U.S. equities, the data show. That compares with 45 percent in September 2007, a month before the S&P 500 reached its record high of 1,565.15 and began a 17-month plunge that erased $11 trillion from the value U.S. shares.

But hold on a mintue– here is the part I find most fascinating about the article: no one can agree on the valuation. (I guess the tendency to cover both sides of the story in the same article comes from political opinion coverage, where the media thinks they have to give equal time to both sides, whether rational or not.)

David Rosenberg, chief economist of Gluskin Sheff & Associates Inc., says U.S. stocks are poised for losses because they’ve become too expensive. The S&P 500 is valued at 22.1 times annual earnings from the past 10 years, according to inflation-adjusted data since 1871 tracked by Yale University Professor Robert Shiller.

So while you have reputable analysts arguing that the market is cheap, you have equally reputable analysts arguing that the market is expensive! How does that happen? Well, it happens because everyone in the value camp operates from a (sometimes radically) different set of assumptions. Are you using trailing estimates, forward estimates, or 10-year normalized estimates? And, by the way, they are estimates.

Source: DenverPost.com

Relative strength is nice because it is precise. No one argues about what the trailing 6-month or 12-month return was. It’s cut and dried. Although different firms use slightly different relative strength calculations–Dorsey, Wright Money Management has a proprietary method–it is hard to imagine a scenario where there would be much disagreement about the strength or weakness of the same market.

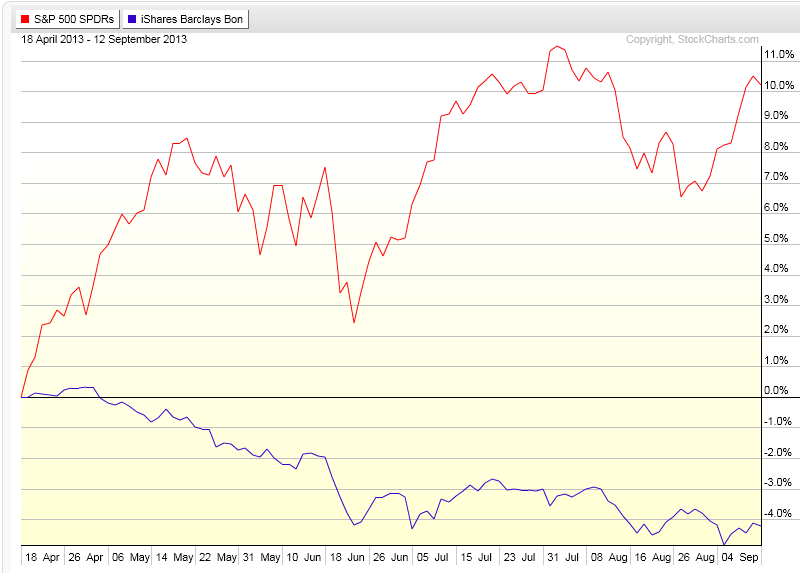

Which is stronger, U.S. stocks or U.S. long-term bonds? Just looking at a comparative chart of the two assets makes it obvious, even to someone not sophisticated in quantitative analysis (SPY vs. TLT).

Click to enlarge. Source: Yahoo! Finance

On the other hand, determining which asset is a better value is quite indeterminate. It all depends on whether you take as your starting point the view that the U.S. stock market is cheap or expensive!

And what happens when you have to value a multi-asset portfolio? How do you determine whether real estate, international stocks, euros, or emerging market bonds are cheaper? The lack of agreed-upon metrics between markets, let alone within an individual market, make this kind of decision a nightmare from a valuation perspective.

Since prior performance is precise, relative strength measurements can be made easily and without argument. Relative strength can easily be used for multi-asset portfolios as well. And finally, the returns from using the relative strength factor are high–as high as the returns from the value factor, and in many studies, higher. Luckily for us, efficient-market types normally decline to use relative strength because theoretically it shouldn’t work! Their loss is our gain.

—-this article originally appeared 4/26/2010. The broad market is up about 40% since this article was written and the debate about valuations is still raging! That alone should tell you that trying to figure out who is right—and whether to invest or not—is not a productive use of time. Relative strength simply indicates what the strongest markets are at any given time.