This is a phrase popularized by the folks at PIMCO to denote a long period of slow economic growth and subpar equity returns. Forbes described their outlook like this:

According to the Pimco party line, those implications are rather grim for the U.S. A year ago Gross told FORBES that our future will likely include a lowered living standard, high unemployment, stagnant corporate profits, heavy government intervention in the economy and disappointing equity returns. Nor, with interest rates already low, can investors expect much from bonds, other than their mediocre coupons.

PIMCO is not the only firm in this camp. Other observers have talked about forward-looking returns for the stock market in the 5% range for the next decade. Here’s John Hussman in a recent commentary:

As a result of last week’s decline, the S&P 500 ended Friday priced, by our estimates, to achieve an average annual 10-year total return of about 4.9%, which is an improvement from the 3.4% level we observed a few months ago, but is nowhere near what would reasonably be viewed as undervalued.

Other observers on valuation are a little less pessimistic, like Jeremy Grantham at GMO, who is looking for returns that might average 8% for the next decade.

Another guru is Aswath Damodaran of NYU, who authored a common textbook on valuation. He wrote recently:

I am not much of a market timer but there is one number I do track on a consistent basis: the equity risk premium. I follow it for two reasons. First, it is a key input in estimating the cost of equity, when valuing individual companies. Second, it offers a window into the market mood, rising during market crises.

For the ERP to play this role, it has to be forward looking and dynamic. The. conventional approach of looking at the past won’t accomplish this. You can however use the current level of the index, with expected cashflows, to back out an expected return on stocks. (Think of it as an IRR for equities.) You can check out the spreadsheet that does this, on my website (http://www.damodaran.com) on the front page.Here is the link for the July 1 spreadsheet. Just replace the index and T.Bond rate with the current level and use the Goal seek in excel:

http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/pc/implprem/ERPJune11.xls

A little history on this “implied ERP”: it was between 3 and 3.5% through much of the 1960s, rose during the 1970s to peak at 6.5% in 1978 and embarked on a two decade decline to an astoundingly low 2% at the end of 1999 (the peak of the dot com boom). The dot com correction pushed it back to about 4% in 2002, where it stagnated until September 2008. The banking-induced crisis caused it to almost double by late November 2008. As the fear subsided, the premium dropped back to pre-crisis levels by January 2010. I have the month-by-month gyrations on my site, also on the front page. http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/pc/implprem/ERPbymonth.xls

Now, to the present. The ERP started this year at 5.20% and gradually climbed to 5.92% at the start of August. Today (8/8/11) at 11.15 am, in the midst of market carnage, with the S&P 500 at 1166 and the 10-year T. Bond at 2.41%, the implied ERP stood at 6.62%.

In this case, the expected return on stocks would be about 9.03% (2.41% plus an equity risk premium of 6.62%).

Why am I bringing all of this up, as I am clearly no expert on valuation or value investing? Well, for a couple of reasons. First, these commentators are largely driven by data, not opinions. Both Hussman and Damodaran, for example, have long-standing models and they change their minds when the data changes. Second, even within the camp that uses robust valuation models, there is quite a range of expectations. Hussman’s model suggests that the market is not undervalued, but Damodaran’s work shows the equity risk premium at multi-decade highs.

That the new normal will happen is no slam dunk, but it’s certainly not out of the question. After all, equity market returns have been extremely anemic over the last ten years and Japan’s experience shows that such a situation can last for much longer than anyone expects. The prospect of another decade of lousy returns is discouraging enough to keep many investors on the sidelines.

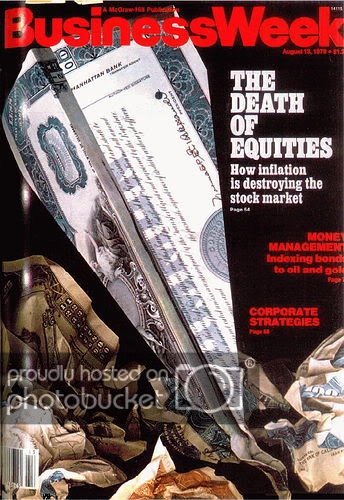

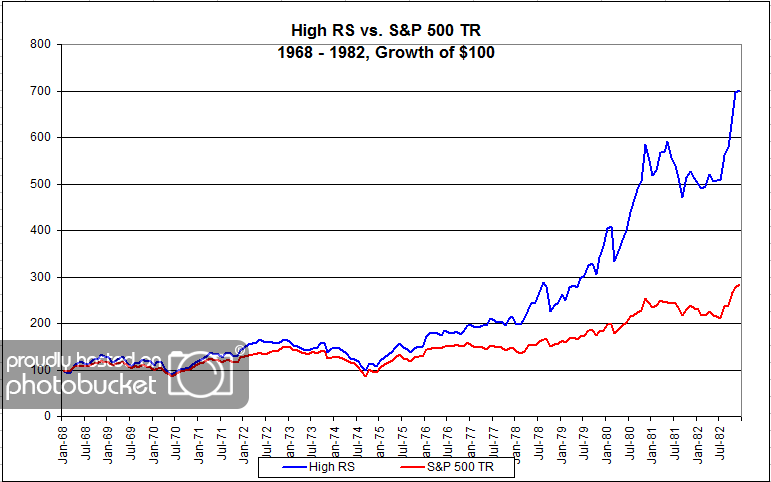

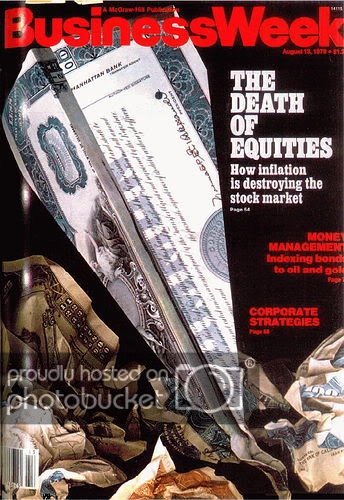

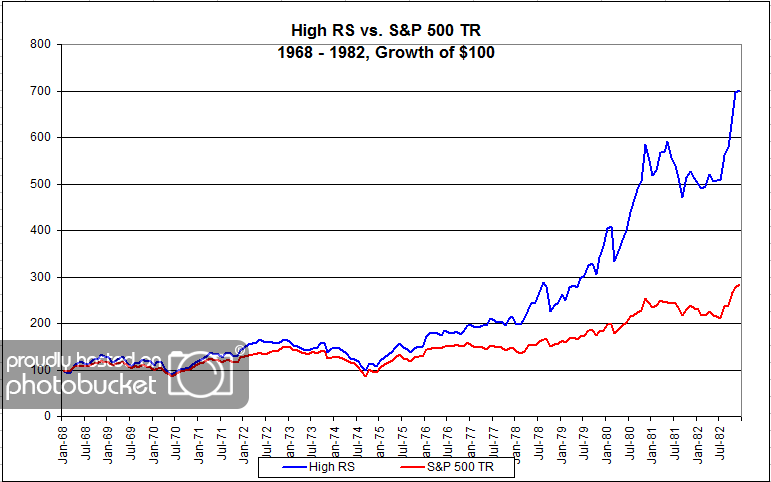

To help understand what the new normal might mean for relative strength investors, J.P. dug into US stock market data from the 1968-1982 period. This period is roughly analogous to our current markets, at least perhaps psychologically. 1968 saw a bear market for speculative names (2000-02), followed by a mega-bear market in 1973-74 in which blue chips got torched as well (2008). The public was turned off to stocks in general, culminating in disgust with the 1979 “Death of Equities” Business Week cover. The S&P 500 total return for the period was 7.2% annualized. Prices barely moved, but dividend yields were reasonably high and accounted for more of the total return than capital appreciation.

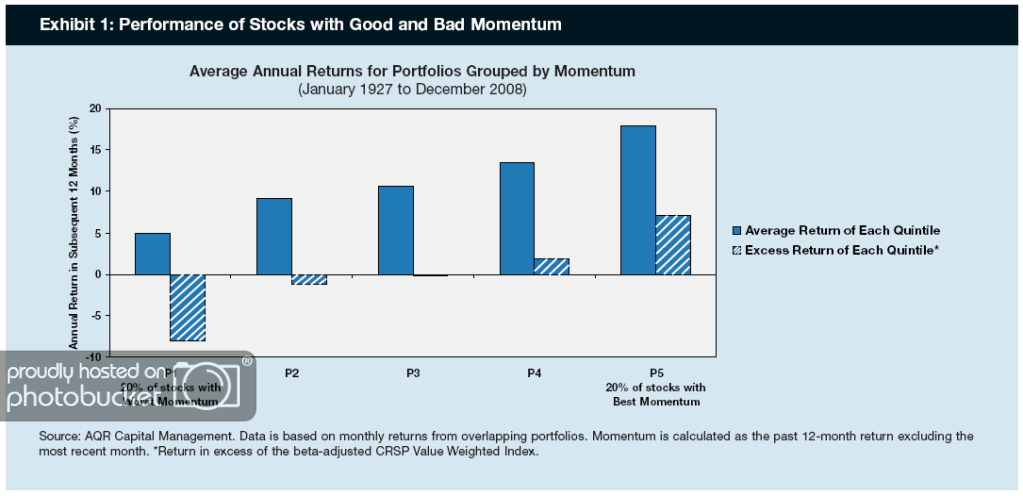

To get a robust estimate for relative strength returns during this period, J.P. went to the database of Ken French at Dartmouth. He looked at returns for portfolios formed from the top half of market capitalization (large cap) and the top third in relative strength. Dr. French constructs his relative strength ranks by calculating the 12-month trailing return, less the return of the most recent month. The portfolio is rebalanced each month with any new names. (Incidentally, this is the same model used by the AQR Momentum Fund.)

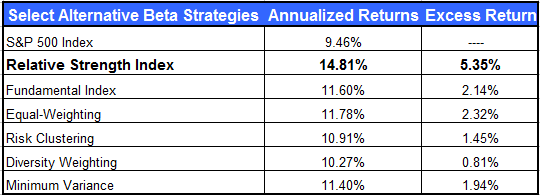

Source: Dorsey, Wright Money Management

As you can see, the new normal is not necessarily a problem for a disciplined relative strength investor. Although market returns were 7.2% annualized, the high relative strength segment returns were about 13.9% per year. It may be fashionable to talk gloom and doom, but the data is clear that good returns are still available in some segments of the market—even if the broad indexes don’t go anywhere.

Note: this chart may well understate the high RS returns, since Dr. French’s database does not incorporate total returns. Looking at price returns only, the comparison would be 13.9% annually for high RS and 2.3% annually for the market.