Every time I read an article about how active investing is hopeless, I shake my head. Most of the problem is investor behavior, not active investing. The data on this has been around for a while, but is ignored by indexing fans. Consider for example, this article in Wealth Management that discusses a 2011 study conducted by Morningstar and the Investment Company Institute. What they found doesn’t exactly square out with most of what you read. Here are some excerpts:

But studies by Morningstar and the Investment Company Institute (ICI) suggest that fund shareholders may not be so dumb after all. According to the latest data, investors gravitate to low-cost funds with strong track records. “People make reasonably intelligent choices when they pick active funds,” says John Rekenthaler, Morningstar’s vice president of research.

The academic approach produces a distorted picture, says Rekenthaler. “It doesn’t matter what percentage of funds trail the index,” says Rekenthaler. “What matters most is how the big funds do. That’s where most of the money is.”

In order to get a realistic picture of fund results, Rekenthaler calculated asset-weighted returns—the average return of each invested dollar. Under his system, large funds carry more weight than small ones. He also calculated average returns, which give equal weight to each fund. Altogether Morningstar looked at how 16 stock-fund categories performed during the ten years ending in 2010. In each category, the asset-weighted return was higher than the result that was achieved when each fund carried the same weight.

Consider the small-growth category. On an equal-weighted basis, active funds returned 2.89 percent annually and trailed the benchmark, which returned 3.78 percent. But the asset-weighted figure for small-growth funds exceeded the benchmark by 0.20 percentage points. Categories where active funds won by wide margins included world stock, small blend, and health. Active funds trailed in large blend and mid growth. The asset-weighted result topped the benchmark in half the categories. In most of the eight categories where the active funds lagged, they trailed by small margins. “There is still an argument for indexing, but the argument is not as strong when you look at this from an asset-weighted basis,” says Rekenthaler.

The numbers indicate that when they are choosing from among the many funds on the market, investors tend to pick the right ones.

Apparently investors aren’t so dumb when it comes to deciding which funds to buy. Most of the actively invested money in the mutual fund industry is in pretty good hands. Academic studies, which weight all funds equally regardless of assets, don’t give a very clear picture of what investors are actually doing.

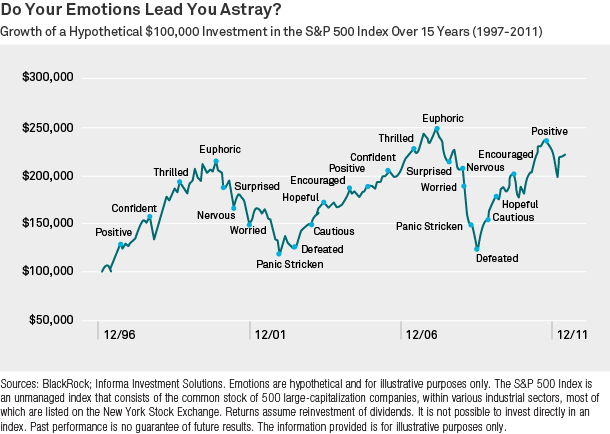

Where, then, is the big problem with active investing? There isn’t one—the culprit is investor behavior. As the article points out:

But investors display remarkably bad timing for their purchases and sales. Studies by research firm Dalbar have shown that over the past two decades, fund investors have typically bought at market peaks and sold at troughs.

Active investing is alive and well. (I added the bold.) In fact, the recent trend toward factor investing, which is just a very systematic method for making active bets, reinforces the value of the approach.

The Morningstar/ICI research just underscores that much of the value of an advisor may lie in helping the client control their emotional impulse to sell when they are fearful and to buy when they feel confident. I think this is often overlooked. If your client has a decent active fund, you can probably help them more by combatting their destructive timing than you can by switching them to an index fund. After all, owning an index fund does not make the investor immune to emotions after a 20% drop in the stock market!