July 1, 2013

Our latest sentiment survey was open from 6/21/13 to 6/28/13. The Dorsey, Wright Polo Shirt Raffle continues to drive advisor participation, and we greatly appreciate your support! This round, we had 64 advisors (same as last time! thanks!) participate in the survey. If you believe, as we do, that markets are driven by supply and demand, client behavior is important. We’re not asking what you think of the market—since most of our blog readers are financial advisors, we’re asking instead about the behavior of your clients. Then we’re aggregating responses exclusively for our readership. Your privacy will not be compromised in any way.

After the first 30 or so responses, the established pattern was simply magnified, so we are fairly comfortable about the statistical validity of our sample. Some statistical uncertainty this round comes from the fact that we only had four investors say that thier clients are more afraid of missing a stock upturn than being caught in a downdraft. Most of the responses were from the U.S., but we also had multiple advisors respond from at least two other countries. Let’s get down to an analysis of the data! Note: You can click on any of the charts to enlarge them.

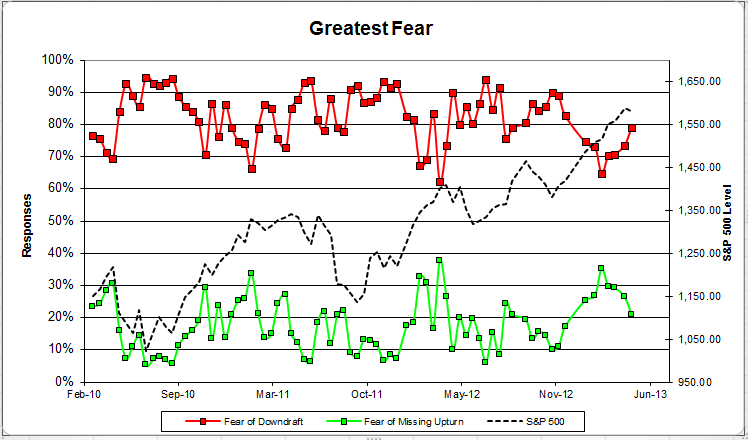

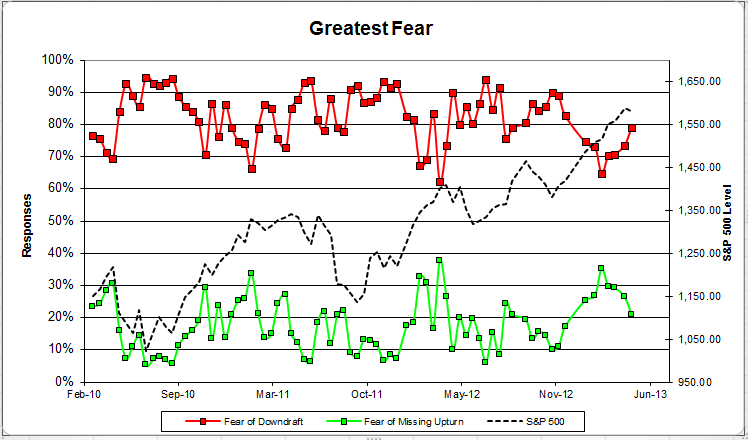

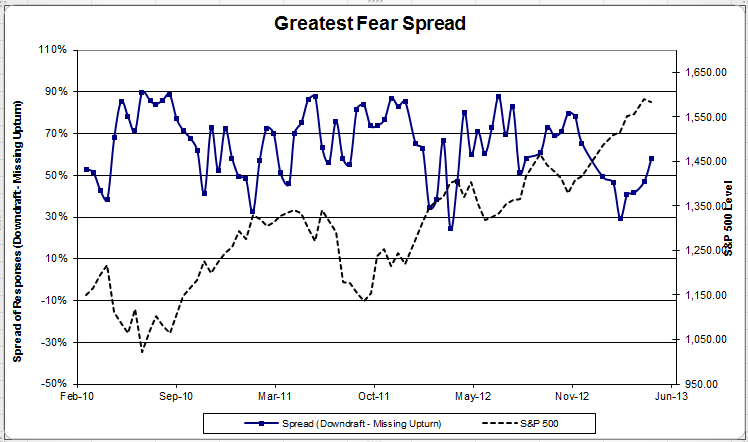

Question 1. Based on their behavior, are your clients currently more afraid of: a) getting caught in a stock market downdraft, or b) missing a stock market upturn?

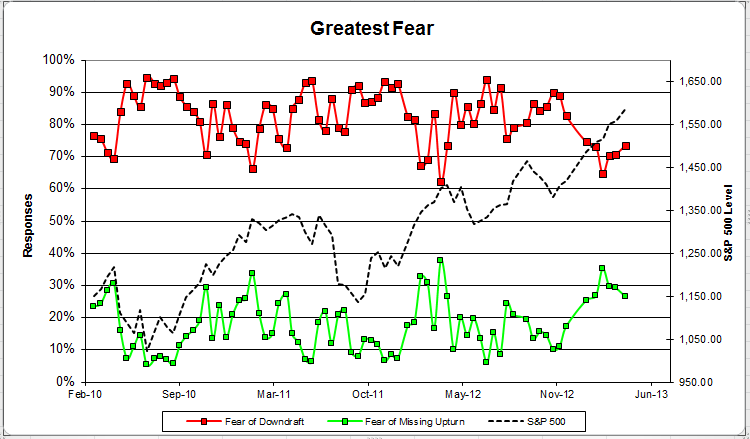

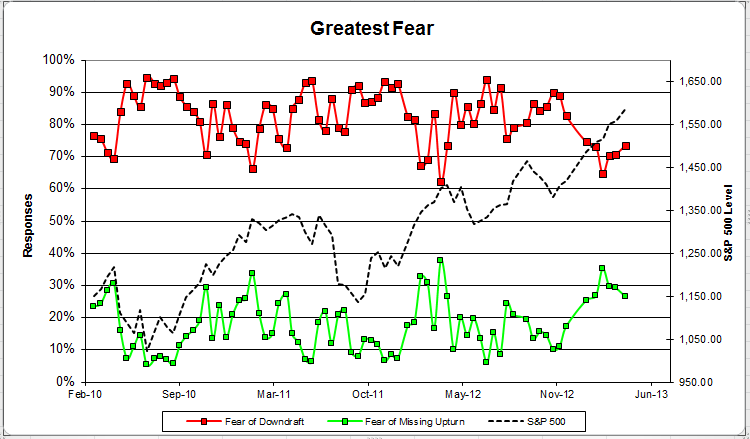

Chart 1: Greatest Fear. From survey to survey, the market fell over -3%, and all of our indicators showed a decline in positive client sentiment. The fear of decline group rose from 75% to 84%. On the flip side, the fear of missing an upturn group fell from 25% to 16%.

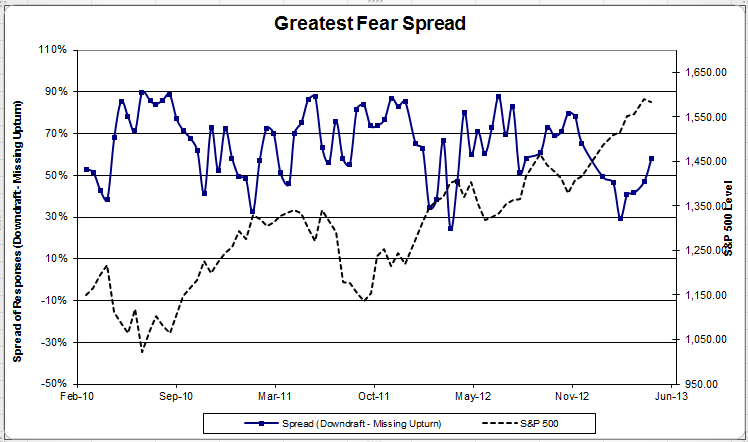

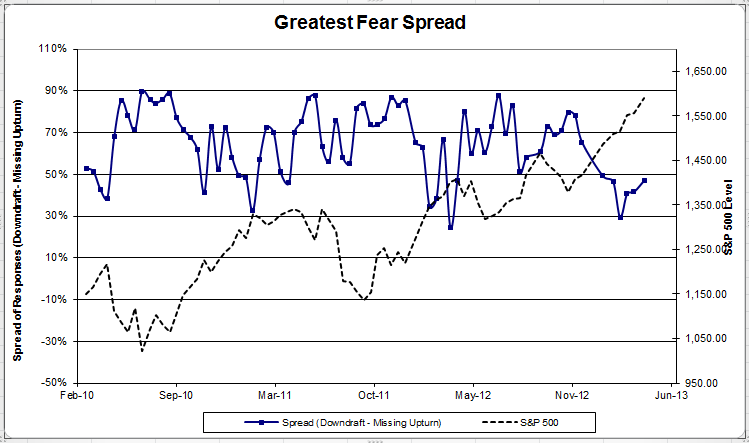

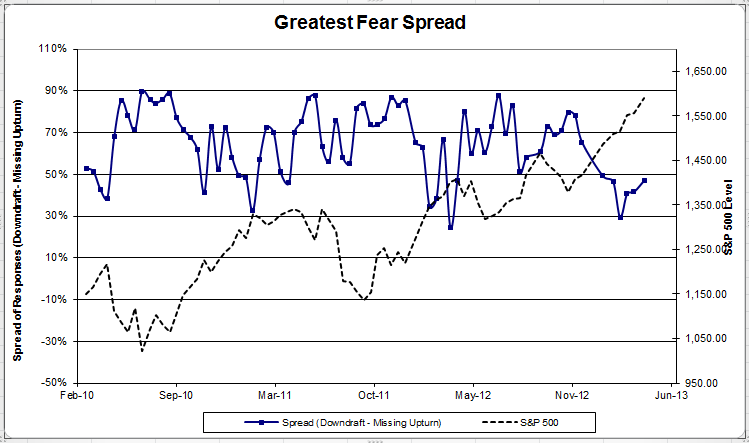

Chart 2: Greatest Fear Spread. Another way to look at this data is to examine the spread between the two groups. The spread moved higher again, from 49% to 68%.

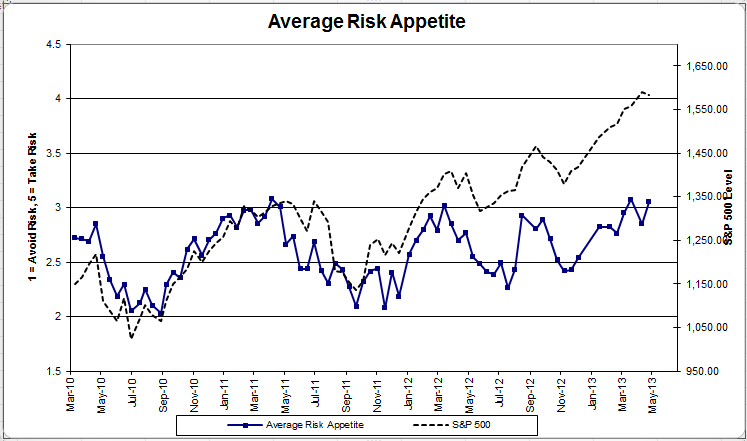

Question 2. Based on their behavior, how would you rate your clients’ current appetite for risk?

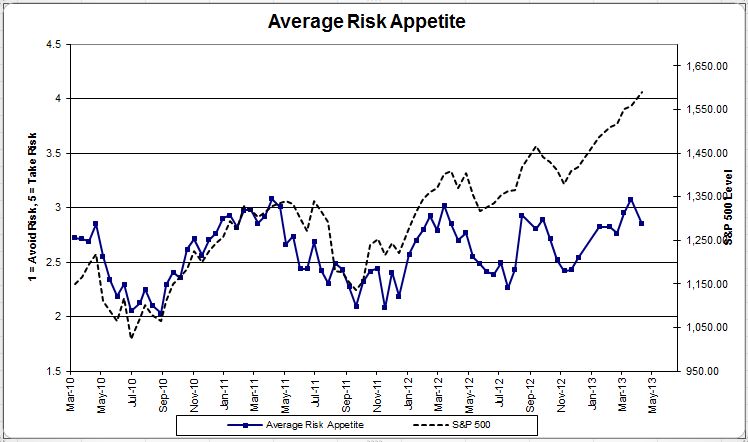

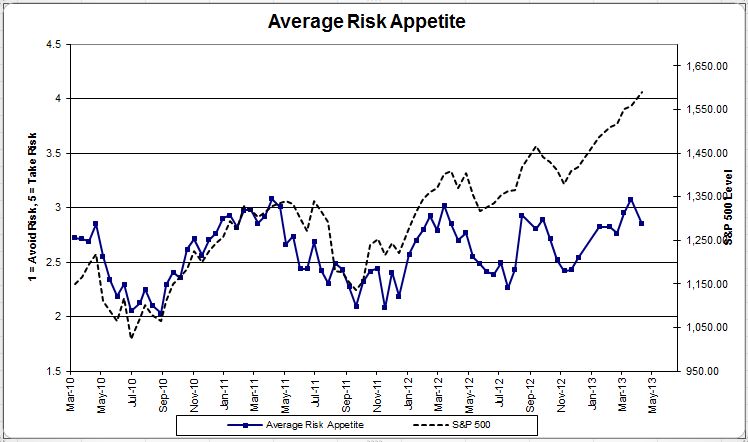

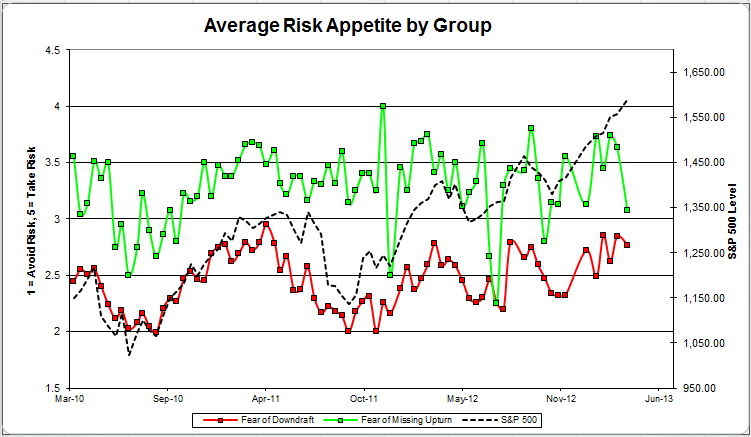

Chart 3: Average Risk Appetite. Average risk appetite fell with the market this round, from 2.90 to 2.71.

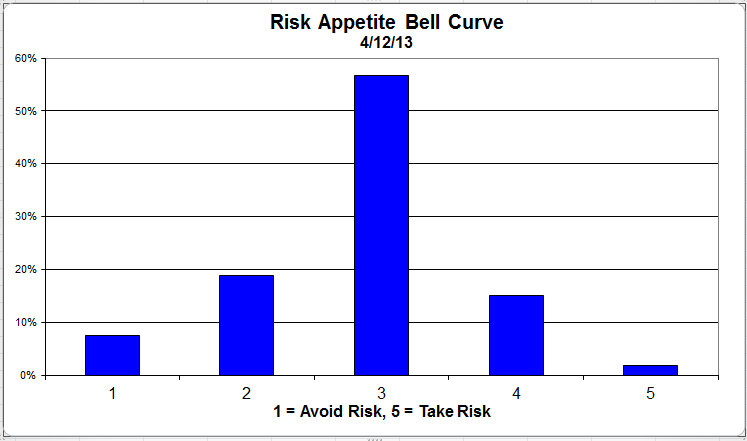

Chart 4: Risk Appetite Bell Curve. This chart uses a bell curve to break out the percentage of respondents at each risk appetite level. This round, just under 50% of all respondents wanted a risk appetite of 3.

Chart 5: Risk Appetite Bell Curve by Group. The next three charts use cross-sectional data. The chart plots the reported client risk appetite separately for the fear of downdraft and for the fear of missing upturn groups. We can see the upturn group wants more risk, while the fear of downturn group is looking for less risk.

Chart 6: Average Risk Appetite by Group. This round, both groups’ risk appetite moved lower in a falling market.

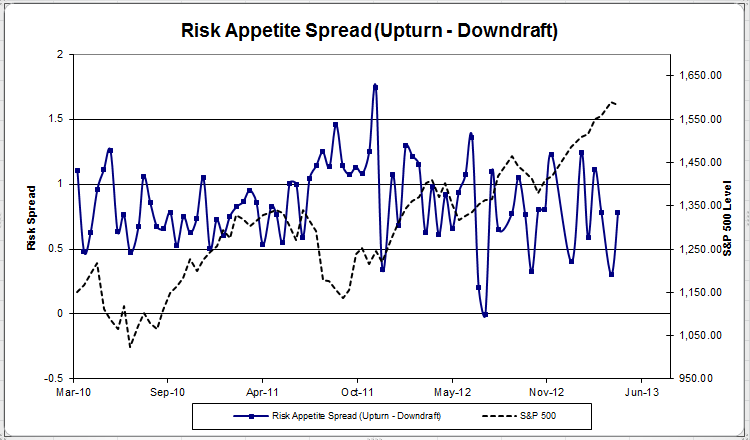

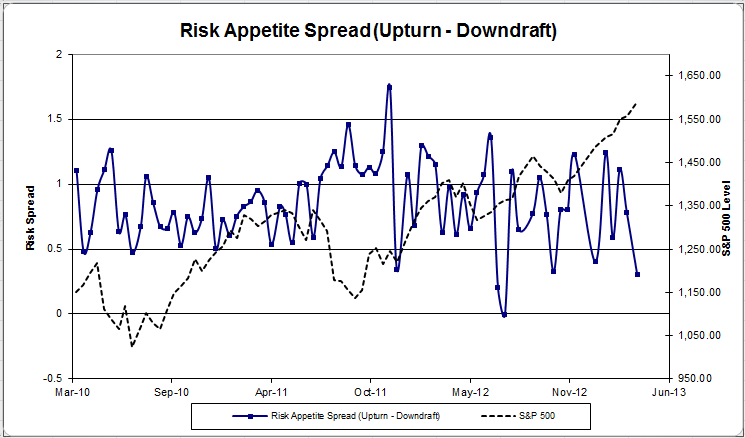

Chart 7: Risk Appetite Spread. This is a chart constructed from the data in Chart 6, where the average risk appetite of the downdraft group is subtracted from the average risk appetite of the missing upturn group. The spread continues to trade within its normal range.

The S&P 500 has experienced the dreaded summer doldrums, and client sentiment has responded in kind. All of our indicators responded to the recent S&P drawdown as expected, with client fear levels rising and risk appetite falling. Hopefully the summer can end a little bit more peacefully than it started. The S&P is still up by a good measure for the year.

No one can predict the future, as we all know, so instead of prognosticating, we will sit back and enjoy the ride. A rigorously tested, systematic investment process provides a great deal of comfort for clients during these types of fearful, highly uncertain market environments. Until next time, good trading and thank you for participating.

4 Comments |

4 Comments |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

JP Lee

June 28, 2013

Jason Zweig has written one of the best personal finance columns for years, The Intelligent Investor for the Wall Street Journal. Today he topped it with a piece that describes his vision of personal finance writing. He describes his job as saving investors from themselves. It is a must read, but I’ll give you a couple of excerpts here.

I was once asked, at a journalism conference, how I defined my job. I said: My job is to write the exact same thing between 50 and 100 times a year in such a way that neither my editors nor my readers will ever think I am repeating myself.

That’s because good advice rarely changes, while markets change constantly. The temptation to pander is almost irresistible. And while people need good advice, what they want is advice that sounds good.

The advice that sounds the best in the short run is always the most dangerous in the long run. Everyone wants the secret, the key, the roadmap to the primrose path that leads to El Dorado: the magical low-risk, high-return investment that can double your money in no time. Everyone wants to chase the returns of whatever has been hottest and to shun whatever has gone cold. Most financial journalism, like most of Wall Street itself, is dedicated to a basic principle of marketing: When the ducks quack, feed ‘em.

In practice, for most of the media, that requires telling people to buy Internet stocks in 1999 and early 2000; explaining, in 2005 and 2006, how to “flip” houses; in 2008 and 2009, it meant telling people to dump their stocks and even to buy “leveraged inverse” exchange-traded funds that made explosively risky bets against stocks; and ever since 2008, it has meant touting bonds and the “safety trade” like high-dividend-paying stocks and so-called minimum-volatility stocks.

It’s no wonder that, as brilliant research by the psychologist Paul Andreassen showed many years ago, people who receive frequent news updates on their investments earn lower returns than those who get no news. It’s also no wonder that the media has ignored those findings. Not many people care to admit that they spend their careers being part of the problem instead of trying to be part of the solution.

My job, as I see it, is to learn from other people’s mistakes and from my own. Above all, it means trying to save people from themselves. As the founder of security analysis, Benjamin Graham, wrote in The Intelligent Investor in 1949: “The investor’s chief problem – and even his worst enemy – is likely to be himself.”

……..

From financial history and from my own experience, I long ago concluded that regression to the mean is the most powerful law in financial physics: Periods of above-average performance are inevitably followed by below-average returns, and bad times inevitably set the stage for surprisingly good performance.

But humans perceive reality in short bursts and streaks, making a long-term perspective almost impossible to sustain – and making most people prone to believing that every blip is the beginning of a durable opportunity.

……..

But this time is never different. History always rhymes. Human nature never changes. You should always become more skeptical of any investment that has recently soared in price, and you should always become more enthusiastic about any asset that has recently fallen in price. That’s what it means to be an investor.

Simply brilliant. Unless you write a lot, it seems deceptively easy to write this well and clearly. It is not. More important, his message that many investment problems are actually investor behavior problems is very true—and has been true forever.

To me, one of the chief advantages of technical analysis is that it recognizes that human nature never changes and that, as a result, behavior patterns recur again and again. Investors predictably panic when market indicators get deeply oversold, just when they should consider buying. Investors predictably want to pile into a stock that has been a huge long-term winner when it breaks a long-term uptrend line—because “it’s a bargain”—just when they might want to think about selling. Responding deliberately at these junctures doesn’t usually require the harrowing activity level that CNBC commentators seem to believe is necessary, but can be quite effective nonetheless. Technical indicators and sentiment surveys often show these turning points very clearly, but as Mr. Zweig describes elsewhere in the article, the financial universe is arranged to deceive us—or at least to tempt us to deceive ourselves.

Investing is one of the many fields where less really is more.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  From the MM, Investor Behavior | Tagged: behavioral finance, investor behavior, investor sentiment, technical analysis |

From the MM, Investor Behavior | Tagged: behavioral finance, investor behavior, investor sentiment, technical analysis |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

June 21, 2013

Here we have the next round of the Dorsey, Wright Sentiment Survey, the first third-party sentiment poll. Participate to learn more about our Dorsey, Wright Polo Shirt raffle! Just follow the instructions after taking the poll, and we’ll enter you in the contest. Thanks to all our participants from last round.

As you know, when individuals self-report, they are always taller and more beautiful than when outside observers report their perceptions! Instead of asking individual investors to self-report whether they are bullish or bearish, we’d like financial advisors to weigh in and report on the actual behavior of clients. It’s two simple questions and will take no more than 20 seconds of your time. We’ll construct indicators from the data and report the results regularly on our blog–but we need your help to get a large statistical sample!

Click here to take Dorsey, Wright’s Client Sentiment Survey.

Contribute to the greater good! It’s painless, we promise.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

JP Lee

June 12, 2013

From Barry Ritholz at The Big Picture comes a great article about what he calls “competency transference.“ His article was triggered by a Bloomberg story about a technology mogul who turned his $1.8 billion payoff into a bankruptcy just a few years later. Mr. Ritholz points out that the problem is generalizable:

Be aware of what I call The Fallacy of Competency Transference. This occurs when someone successful in one field jumps in to another and fails miserably. The most widely known example is Michael Jordan, the greatest basketball player the game has ever known, deciding he was also a baseball player. He was a .200 minor league hitter.

I have had repeated conversations with Medical Doctors about this: They are extremely intelligent accomplished people who often assume they can do well in markets. (After all, they conquered what I consider a much more challenging field of medicine).

The problem they run into is that competency transference. After 4 years of college (mostly focused on pre-med courses), they spend 4 years in Medical school; another year as an Interns, then as many as 8 years in Residency. Specialized fields may require training beyond residency, tacking on another 1-3 years. This process is at least 12, and as many as 20 years (if we include Board certification).

What I try to explain to these highly educated, highly intelligent people is that they absolutely can achieve the same success in markets that they have as medical professionals — they just have to put the requisite time in, immersing themselves in finance (like they did in medicine) for a decade or so. It is usually around this moment that the light bulb goes off, and the cause of prior mediocre performance becomes understood.

To me, the funny thing is that competency transference mostly applies to the special case of financial markets. For example, no successful stock market professional would ever, ever assume themselves to be a competent thoracic surgeon without the requisite training. Nor would a medical doctor ever assume that he or she could play a professional sport or run a nuclear submarine without the necessary skills. (I think the Michael Jordan analogy is a poor one, since there have been numerous multi-sport athletes. Many athletes letter in multiple sports in high school and some even play more than one in college. Michael Jordan may have been wrong about his particular case, but it wasn’t necessarily a crazy idea.)

Nope, competency transference is mostly restricted to the idea that anyone watching CNBC can become a market maven. (Apparently even talking heads on CNBC believe this.) This creates no end of grief in advisor-client relationships if 1) the advisor isn’t very far up the learning curve, and 2) if the client thinks they know better. You would have the same problem if you had a green medical doctor and you thought you knew more than the doctor did. That is a situation that is ripe for problems!

Advisors need to work continuously to expand their skills and knowledge if they are to be of use to investors. And investors, in general, would do well to spend their efforts vetting advisors carefully rather than assuming financial markets are a piece of cake.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  From the MM, Investor Behavior, Markets | Tagged: financial markets, investor behavior, stock market |

From the MM, Investor Behavior, Markets | Tagged: financial markets, investor behavior, stock market |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

June 6, 2013

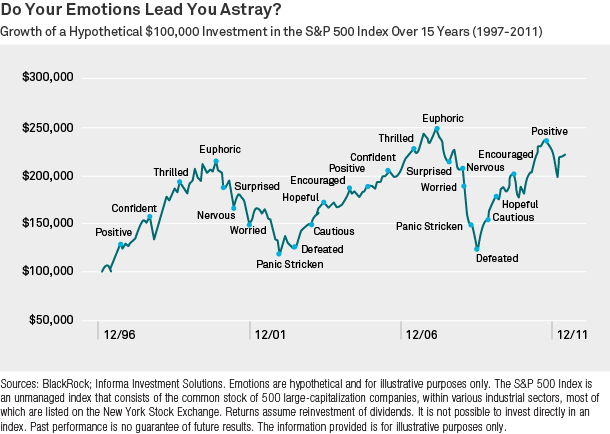

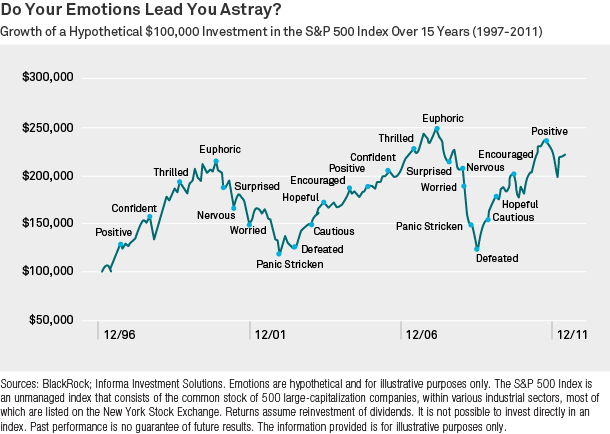

From Josh Brown at The Reformed Broker, a nice picture of investor emotions as they ride the market roller coaster. All credit to Blackrock, who came up with this funny/sad/true graphic.

Blackrock’s emotional roller coaster

(click on image to enlarge)

One of the important roles of a financial advisor, I think, is to keep clients from jumping out of the roller coaster when it is particularly scary. At an amusement park, when people are faced with tangible physical harm, jumping does not seem like a very good idea to them—but investors are tempted to jump out of the market roller coaster all the time.

2 Comments |

2 Comments |  Investor Behavior, Just for Fun, Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: investor sentiment, market |

Investor Behavior, Just for Fun, Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: investor sentiment, market |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

June 6, 2013

Mutual fund flow estimates are derived from data collected by The Investment Company Institute covering more than 95 percent of industry assets and are adjusted to represent industry totals.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets |

Investor Behavior, Markets |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

JP Lee

June 5, 2013

Motley Fool had an excellent article by Morgan Housel on a couple of the most common cognitive biases that cause problems for investors, cognitive dissonance and confirmation bias. The information is not new, but what makes this article so fun is Housel’s writing style and good analogies. A couple of excerpts should suffice to illuminate the problem with cognitive biases.

Study successful investors, and you’ll notice a common denominator: They are masters of psychology. They can’t control the market, but they have complete control over the gray matter between their ears.

And lucky them. Most of us, on the other hand, are mental catastrophes. As investor Barry Ritholtz once put it:

You’re a monkey. It all comes down to that. You are a slightly clever, pants-wearing primate. If you forget that you’re nothing more than a monkey who has been fashioned by eons on the plains, being chased by tigers, you shouldn’t invest. You have to be aware of how your own psychology affects what you do.

Take one of the most powerful theories in behavior psychology: cognitive dissonance. It’s the term psychologists use for the uncomfortable feeling you get when having two conflicting thoughts at the same time. “Smoking is bad for me. I’m going to go smoke.” That’s cognitive dissonance.

We hate cognitive dissonance, and jump through hoops to reduce it. The easiest way to reduce it is to engage in mental gymnastics that justifies behavior we know is wrong. “I had a stressful day and I deserve a cigarette.” Now you can smoke guilt-free. Problem solved.

Classic. And this:

Cognitive dissonance is especially toxic in the emotional cesspool that is managing money. Raise your hand if this is you:

- You criticize Wall Street for being a casino while checking your portfolio twice a day.

- You sold your stocks in 2009 because the Fed was printing money. When stocks doubled in value soon after, you blamed it on the Fed printing money.

- You put $1,000 on a hyped penny stock your brother convinced you is the next Facebook. After losing everything, you tell yourself you were just investing for the entertainment.

- You call the government irresponsible for running a deficit while simultaneously saddling yourself with an unaffordable mortgage.

- You buy a stock only because you think it’s cheap. When you realize you were wrong, you decide to hold it because you like the company’s customer service.

Almost all of us do something similar with our money. We have to believe our decisions make sense. So when faced with a situation that doesn’t make sense, we fool ourselves into believing something else.

And this about confirmation bias:

Worse, another bias — confirmation bias — causes us to bond with people whose self-delusions look like our own. Those who missed the rally of the last four years are more likely to listen to analysts who forecast another crash. Investors who feel burned by the Fed visit websites that share the same view. Bears listen to fellow bears; bulls listen to fellow bulls.

Before long, you’ve got a trifecta of failure: You make a bad decision, rationalize it by fighting cognitive dissonance, and reinforce it with confirmation bias. No wonder the average investor does so poorly.

It’s worth reading the whole article, but the gist of it is that we are all susceptible to these cognitive biases. It’s possible to mitigate the problem with some kind of systematic investment process, but you still have to be careful that you’re not fooling yourself. Investing well is not easy and mastering one’s own psyche may be the most difficult part of all.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Investor Behavior | Tagged: behavioral finance, investor behavior, systematic investment process |

Investor Behavior | Tagged: behavioral finance, investor behavior, systematic investment process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

May 29, 2013

Here we have the next round of the Dorsey, Wright Sentiment Survey, the first third-party sentiment poll. Participate to learn more about our Dorsey, Wright Polo Shirt raffle! Just follow the instructions after taking the poll, and we’ll enter you in the contest. Thanks to all our participants from last round.

As you know, when individuals self-report, they are always taller and more beautiful than when outside observers report their perceptions! Instead of asking individual investors to self-report whether they are bullish or bearish, we’d like financial advisors to weigh in and report on the actual behavior of clients. It’s two simple questions and will take no more than 20 seconds of your time. We’ll construct indicators from the data and report the results regularly on our blog–but we need your help to get a large statistical sample!

Click here to take Dorsey, Wright’s Client Sentiment Survey.

Contribute to the greater good! It’s painless, we promise.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

JP Lee

May 15, 2013

This is the title of a nice article by Brett Arends at Marketwatch. He points out that a lot of our assumptions, especially regarding risk, are open to question.

Risk is an interesting topic for a lot of reasons, but principally (I think) because people seem to be obsessed with safety. People gravitate like crazy to anything they perceive to be “safe.” (Arnold Kling has an interesting meditation on safe assets here.)

Risk, though, is like matter–it can neither be created nor destroyed. It just exists. When you buy a safe investment, like a U.S. Treasury bill, you are not eliminating your risk; you are just switching out of the risk of losing your money into the risk of losing purchasing power. The risk hasn’t gone away; you have just substituted one risk for another. Good investing is just making sure you’re getting a reasonable return for the risk you are taking.

In general, investors–and people generally–are way too risk averse. They often get snookered in deals that are supposed to be “low risk” mainly because their risk aversion leads them to lunge at anything pretending to be safe. Psychologists, however, have documented that individuals make more errors from being too conservative than too aggressive. Investors tend to make that same mistake. For example, nothing is more revered than a steady-Eddie mutual fund. Investors scour magazines and databases to find a fund that (paradoxically) is safe and has a big return. (News flash: if such a fund existed, you wouldn’t have to look very hard.)

No one goes looking for high-volatility funds on purpose. Yet, according to an article, Risk Rewards: Roller-Coaster Funds Are Worth the Ride at TheStreet.com:

Funds that post big returns in good years but also lose scads of money in down years still tend to do better over time than funds that post slow, steady returns without ever losing much.

The tendency for volatile investments to best those with steadier returns is even more pronounced over time. When we compared volatile funds with less volatile funds over a decade, those that tended to see big performance swings emerged the clear winners. They made roughly twice as much money over a decade.

That’s a game changer. Now, clearly, risk aversion at the cost of long-term returns may be appropriate for some investors. But if blind risk aversion is killing your long-term returns, you might want to re-think. After all, eating Alpo is not very pleasant and Maalox is pretty cheap. Maybe instead of worrying exclusively about volatility, we should give some consideration to returns as well.

—-this article originally appeared 3/3/2010. A more recent take on this theme are the papers of C. Thomas Howard. He points out that volatility is a short-term factors, while compounded returns are a long-term issue. By focusing exclusively on volatility, we can often damage long term results. He re-defines risk as underperformance, not volatility. However one chooses to conceptualize it, blind risk aversion can be dangerous.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  From the Archives, From the MM, Investor Behavior, Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: behavioral finance, decision-making, investor behavior, return, volatility |

From the Archives, From the MM, Investor Behavior, Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: behavioral finance, decision-making, investor behavior, return, volatility |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

May 7, 2013

Our latest sentiment survey was open from 4/26/13 to 5/3/13. The Dorsey, Wright Polo Shirt Raffle continues to drive advisor participation, and we greatly appreciate your support! This round, we had 57 advisors (same as last time! thanks!) participate in the survey. If you believe, as we do, that markets are driven by supply and demand, client behavior is important. We’re not asking what you think of the market—since most of our blog readers are financial advisors, we’re asking instead about the behavior of your clients. Then we’re aggregating responses exclusively for our readership. Your privacy will not be compromised in any way.

After the first 30 or so responses, the established pattern was simply magnified, so we are fairly comfortable about the statistical validity of our sample. Some statistical uncertainty this round comes from the fact that we only had four investors say that thier clients are more afraid of missing a stock upturn than being caught in a downdraft. Most of the responses were from the U.S., but we also had multiple advisors respond from at least two other countries. Let’s get down to an analysis of the data! Note: You can click on any of the charts to enlarge them.

Question 1. Based on their behavior, are your clients currently more afraid of: a) getting caught in a stock market downdraft, or b) missing a stock market upturn?

Chart 1: Greatest Fear. From survey to survey, the market was basically flat. Our indicators were once again a mixed back. The fear of downdraft group rose from 74% to 79%, while the upturn group fell from 26% to 21%.

Chart 2: Greatest Fear Spread. Another way to look at this data is to examine the spread between the two groups. The spread moved higher again, from 47% to 58%.

Question 2. Based on their behavior, how would you rate your clients’ current appetite for risk?

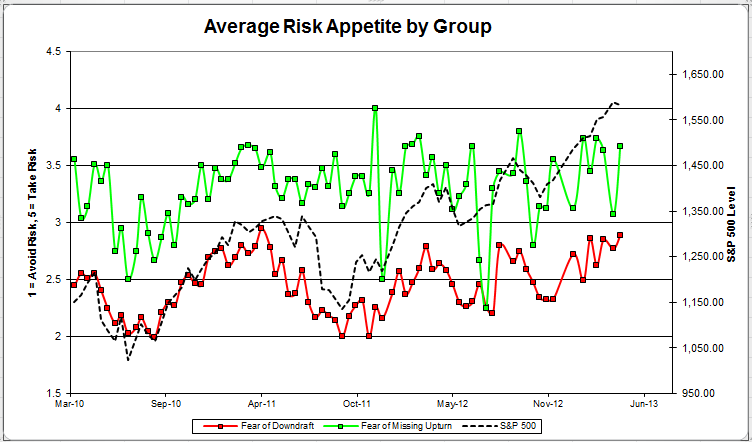

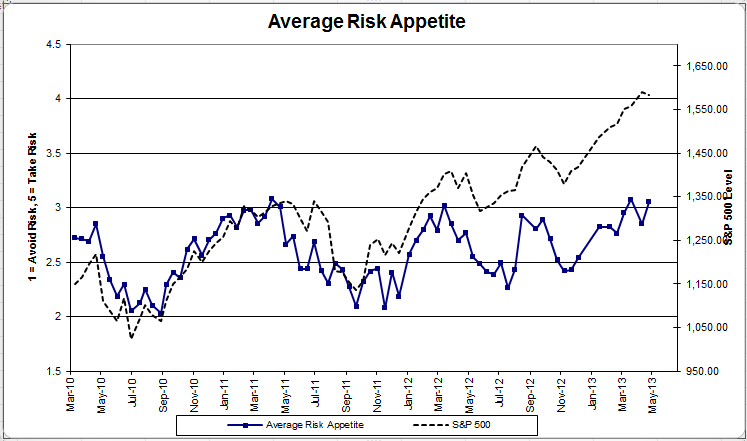

Chart 3: Average Risk Appetite. Average risk appetite bounced this round, from 2.85 to 3.05. We’re sitting just off of all-time risk appetite highs.

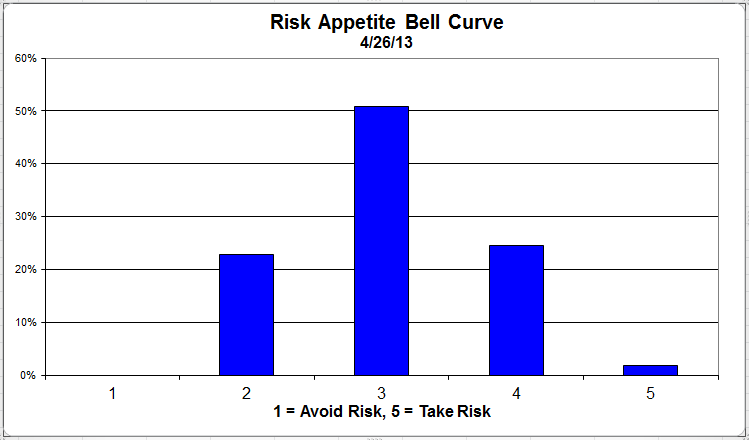

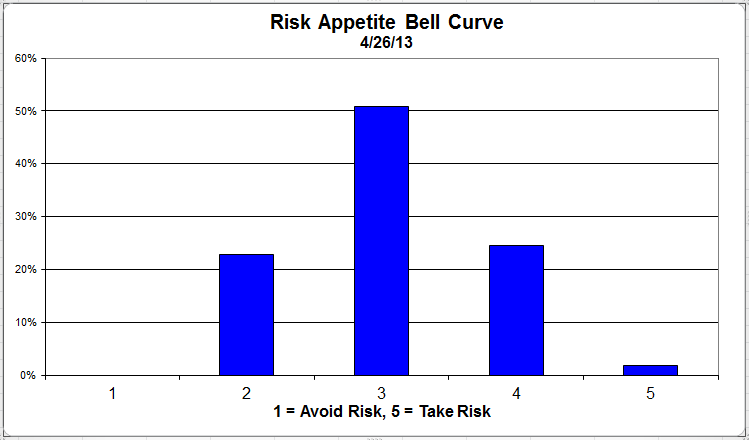

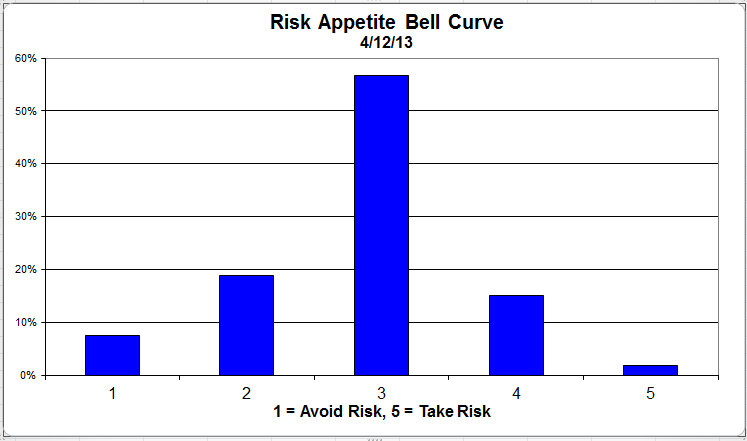

Chart 4: Risk Appetite Bell Curve. This chart uses a bell curve to break out the percentage of respondents at each risk appetite level. This round, over 50% of all respondents wanted a risk appetite of 3.

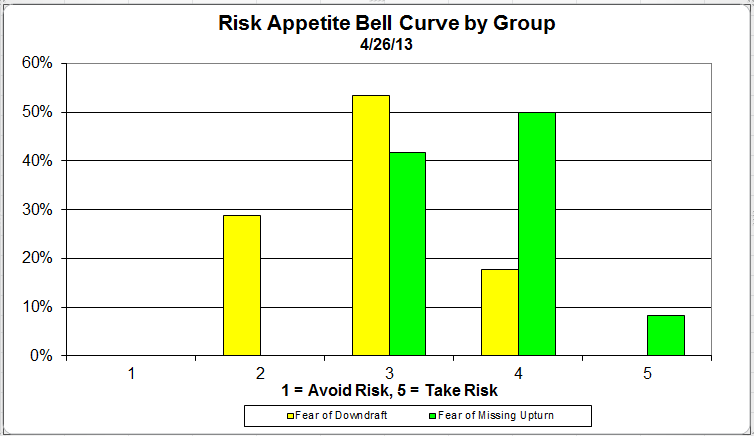

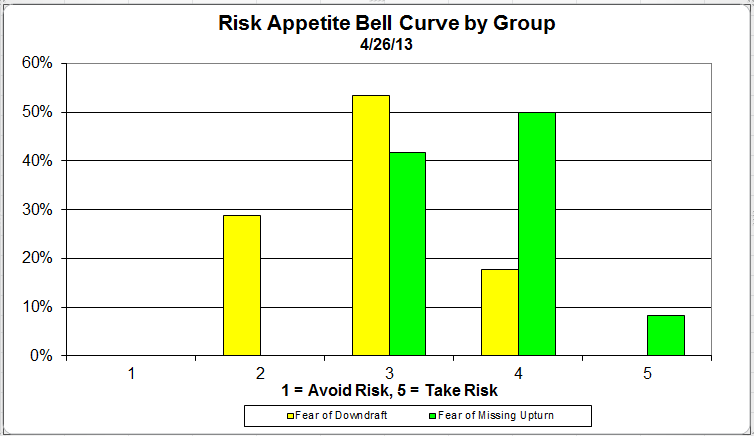

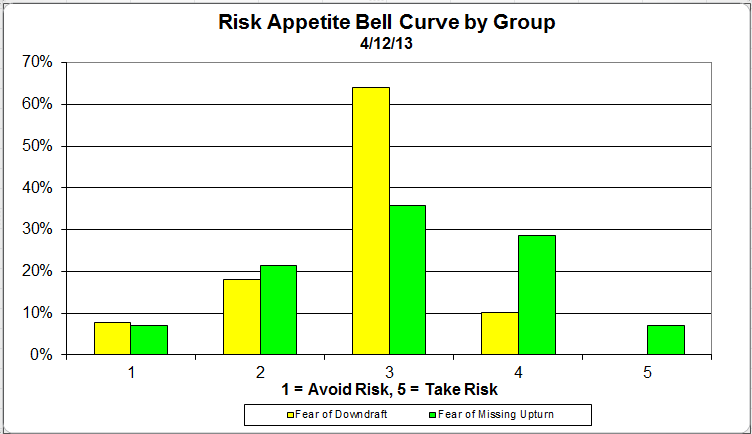

Chart 5: Risk appetite Bell Curve by Group. The next three charts use cross-sectional data. The chat plots the reported client risk appetite separately for the fear of downdraft and for the fear of missing upturn groups. We can see the upturn group wants more risk, while the fear of downturn group is looking for less risk.

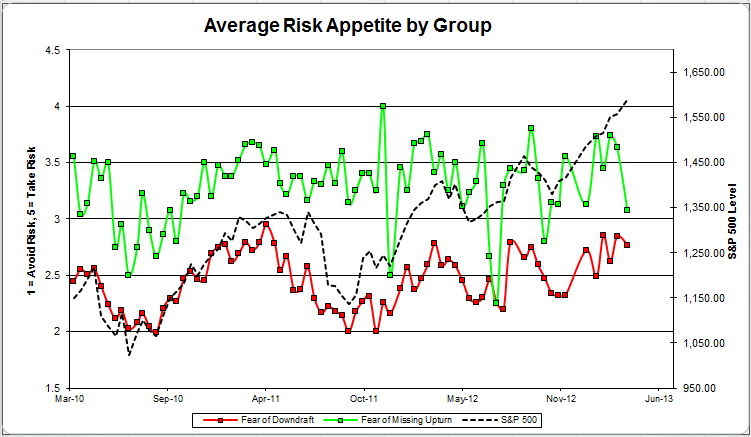

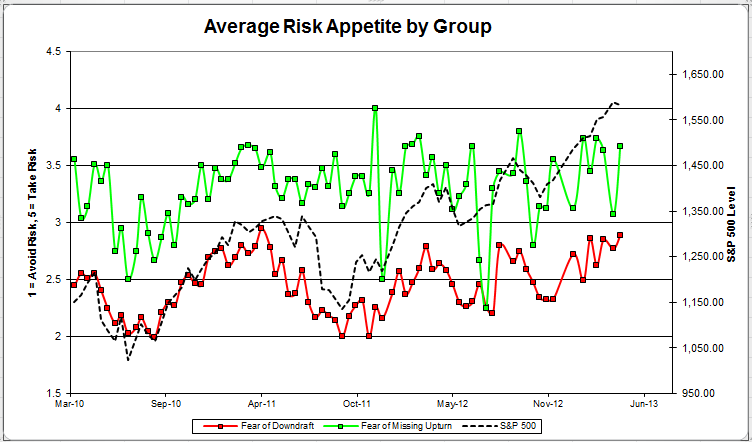

Chart 6: Average Risk Appetite by Group. This round, both groups’ risk appetite moved higher in a flat market.

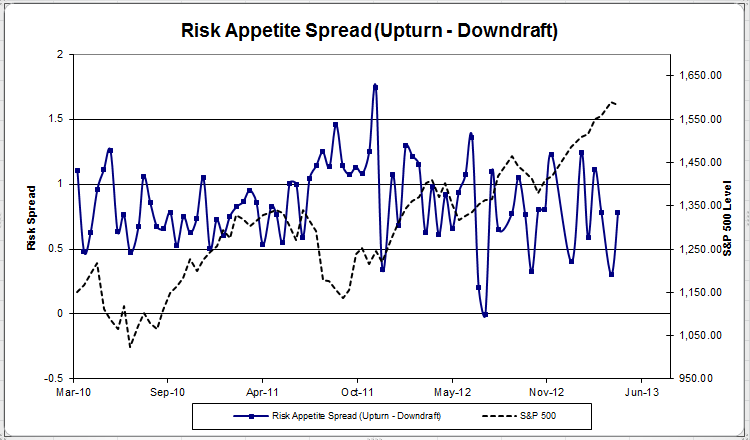

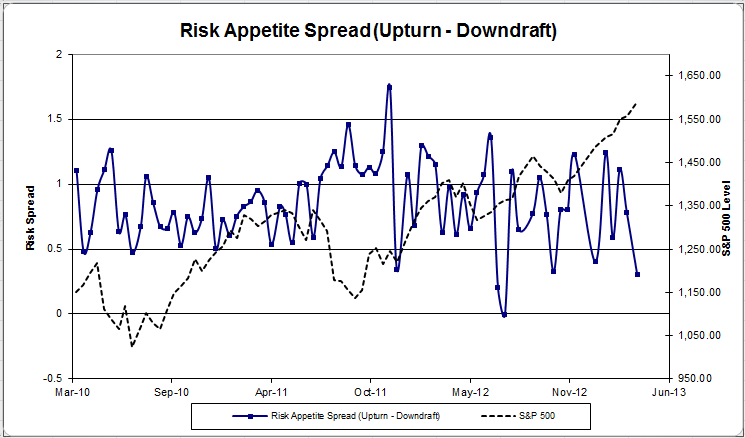

Chart 7: Risk Appetite Spread. This is a chart constructed from the data in Chart 6, where the average risk appetite of the downdraft group is subtracted from the average risk appetite of the missing upturn group. The spread continues to trade within it’s normal range.

From survey to survey, the S&P was basically flat. Client sentiment improved in some of our indicators, and fell in others. Once again we see the overall risk appetite average acting as the most consistent indicator. With client risk appetite near all-time survey highs, and the stock market currently hitting all-time highs, we hope to see those trends remain intact.

No one can predict the future, as we all know, so instead of prognosticating, we will sit back and enjoy the ride. A rigorously tested, systematic investment process provides a great deal of comfort for clients during these types of fearful, highly uncertain market environments. Until next time, good trading and thank you for participating.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

JP Lee

May 6, 2013

We’ve written about the uselessness of forecasting in the past and even cited James Montier’s wonderful piece, The Seven Sins of Fund Management. This citation comes from Mebane Faber’s World Beta blog. Montier writes:

The two most common biases are over-optimism and overconfidence. Overconfidence refers to a situation whereby people are surprised more often than they expect to be. Effectively people are generally much too sure about their ability to predict. This tendency is particularly pronounced amongst experts. That is to say, experts are more overconfident than lay people. This is consistent with the illusion of knowledge driving overconfidence.

Dunning and colleagues have documented that the worst performers are generally the most overconfident. They argue that such individuals suffer a double curse of being unskilled and unaware of it. Dunning et al argue that the skills needed to produce correct responses are virtually identical to those needed to self-evaluate the potential accuracy of responses. Hence the problem.

This is irony in action. Knowledge drives overconfidence, so people who actually know something about a topic are more prone to think they can forecast, and they probably even sound more believable. And finally, the worst performers are the most overconfident!

This may be one of the few instances in which ignorance is bliss. If you have the Zen “beginner’s mind” and don’t make any assumptions about what might happen, you’re going to be better off than if you are knowledgeable and try to guess.

Systematic trend-following eliminates the need to forecast (although apparently not the desire, since we have clients constantly asking us what we think is going to happen). We use relative strength to drive our trend-following; it is able to pick out the strongest trends, and those are the trends we are interested in following. We stay with an asset as long as it remains strong. When it weakens, we kick it out of the portfolio and replace it with something stronger. This kind of casting-out method allows the portfolio to adapt to the market environment, as it is constantly refreshed with new, strong assets.

Despite having a logical and simple method that performs well over time and eliminates the need to forecast, soothsayers will probably always be with us—but your best bet is to ignore them.

—-this article originally appeared 3/2/2013. Of course the lesson is timeless.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  From the Archives, Investor Behavior, Thought Process |

From the Archives, Investor Behavior, Thought Process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

May 3, 2013

Morgan Housel has a fun article at Motley Fool with a possible explanation for why investors are so clueless. His argument, essentially, is that investors confuse the stock market with the economy. If the economy is bad, they assume the stock market must be bad too. Although it’s certainly true that many investors are confused about the linkage between the stock market and the economy, I don’t know if that’s the real explanation or not—but it’s plausible. Maybe I’ve just given up hope that we’ll ever understand investor irrationality! To me, the most staggering part of his article is where he quotes an investor study from Franklin:

Take an annual survey by Franklin Templeton Investments. Near the start of each year, it asks 1,000 investors whether the S&P 500 went up or down in the previous year.

Now, we live in the age of CNBC and Yahoo! Finance and iPhone apps, where no one lacks the data to know a simple statistic like whether the market went up or down.

Yet year after year, the survey shows that swarms of investors are utterly clueless:

-

In 2010, 66% of investors said the S&P 500 fell in 2009. Yet it was actually up 26.5%.

-

In 2011, about half of investors said the market fell in 2010. Yet it was actually up 15%.

-

In 2012, 53% of investors said the market fell in 2011. Yet it was up 2%.

-

Just recently, 31% of investors said the market fell last year. Yet it was up 16%.

Mind-boggling, isn’t it? During a strong three-year run in the market (2009-2011), more than half of the investors they polled thought it was going down! Last year, the idea that the market might be going up began to sink in. Given that the economy was actually growing slowly during much of that time, perhaps investors are imagining market performance is related to their own economic confidence or linked to their own desire to invest. Whatever the linkage, it’s pretty clear they weren’t basing it on market data.

The more data-centric your investing approach is, the more likely it is that you’ll get somewhere close to reality. If you are looking at relative strength data, it’s easier to see where the strongest trending markets have been—and also to see what’s been sinking. A systematic investment process might be your best insurance policy.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets | Tagged: investor behavior |

Investor Behavior, Markets | Tagged: investor behavior |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

April 26, 2013

Here we have the next round of the Dorsey, Wright Sentiment Survey, the first third-party sentiment poll. Participate to learn more about our Dorsey, Wright Polo Shirt raffle! Just follow the instructions after taking the poll, and we’ll enter you in the contest. Thanks to all our participants from last round.

As you know, when individuals self-report, they are always taller and more beautiful than when outside observers report their perceptions! Instead of asking individual investors to self-report whether they are bullish or bearish, we’d like financial advisors to weigh in and report on the actual behavior of clients. It’s two simple questions and will take no more than 20 seconds of your time. We’ll construct indicators from the data and report the results regularly on our blog–but we need your help to get a large statistical sample!

Click here to take Dorsey, Wright’s Client Sentiment Survey.

Contribute to the greater good! It’s painless, we promise.

2 Comments |

2 Comments |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

JP Lee

April 23, 2013

Our latest sentiment survey was open from 4/12/13 to 4/19/13. The Dorsey, Wright Polo Shirt Raffle continues to drive advisor participation, and we greatly appreciate your support! This round, we had 57 advisors participate in the survey. If you believe, as we do, that markets are driven by supply and demand, client behavior is important. We’re not asking what you think of the market—since most of our blog readers are financial advisors, we’re asking instead about the behavior of your clients. Then we’re aggregating responses exclusively for our readership. Your privacy will not be compromised in any way.

After the first 30 or so responses, the established pattern was simply magnified, so we are fairly comfortable about the statistical validity of our sample. Some statistical uncertainty this round comes from the fact that we only had four investors say that thier clients are more afraid of missing a stock upturn than being caught in a downdraft. Most of the responses were from the U.S., but we also had multiple advisors respond from at least two other countries. Let’s get down to an analysis of the data! Note: You can click on any of the charts to enlarge them.

Question 1. Based on their behavior, are your clients currently more afraid of: a) getting caught in a stock market downdraft, or b) missing a stock market upturn?

Chart 1: Greatest Fear. From survey to survey, the S&P 500 rose slightly, and none of our indicators worked correctly. This has to do with when we publish the survey (Friday) and when most people take the survey (Monday). On that Monday, the S&P had a big down day and these results incorporate that move down. The fear of downturn group rose from 71% to 74%. The fear of missing upturn group fell from 29% to 26%.

Chart 2: Greatest Fear Spread. Another way to look at this data is to examine the spread between the two groups. The spread rose from 42% to 47%.

Question 2. Based on their behavior, how would you rate your clients’ current appetite for risk?

Chart 3: Average Risk Appetite. Average risk appetite dropped this round, from 3.08 to 2.85.

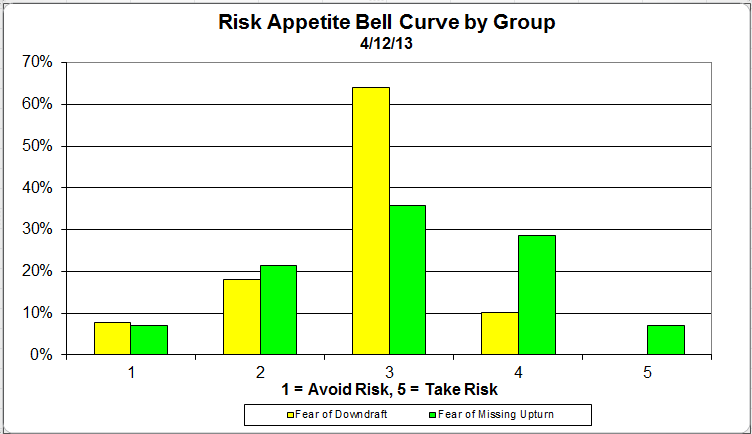

Chart 4: Risk Appetite Bell Curve. This chart uses a bell curve to break out the percentage of respondents at each risk appetite level. This round, over 50% of all respondents wanted a risk appetite of 3.

Chart 5: Risk appetite Bell Curve by Group. The next three charts use cross-sectional data. The chat plots the reported client risk appetite separately for the fear of downdraft and for the fear of missing upturn groups. We can see the upturn group wants more risk, while the fear of downturn group is looking for less risk.

Chart 6: Average Risk Appetite by Group. This round, both groups’ risk appetite fell lower.

Chart 7: Risk Appetite Spread. This is a chart constructed from the data in Chart 6, where the average risk appetite of the downdraft group is subtracted from the average risk appetite of the missing upturn group. The spread dropped this round.

From survey to survey, the S&P rose slightly. However, the market fell steeply when most of our respondents were taking the survey, as evidenced by a sharp pullback in client sentiment. All of the indicators showed a marked decrease in client sentiment. However, this is to be expected somewhat, considering how great the first quarter was. Let’s hope for a small pullback and a continued rally into spring.

No one can predict the future, as we all know, so instead of prognosticating, we will sit back and enjoy the ride. A rigorously tested, systematic investment process provides a great deal of comfort for clients during these types of fearful, highly uncertain market environments. Until next time, good trading and thank you for participating.

3 Comments |

3 Comments |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

JP Lee

April 18, 2013

Relative strength investors will be glad to know that James Picerno’s Capital Spectator blog has an article on the wonders of momentum. He discusses the momentum “anomaly” and its history briefly:

Momentum is one of the oldest and most persistent anomalies in the financial literature. The tendency of positive or negative returns to persist for a time seems like a ridiculously simple predictor, but it works. There’s an ongoing debate about why it works, but the results in numerous tests speak loud and clear. Unlike many (most?) reported sources of alpha, the market-beating and risk-lowering results linked to momentum strategies appear to be immune to arbitrage.

Informally, it’s fair to say that investors have been exploiting momentum in various forms for as long as humans have been trading assets. Formally, the concept dates to at least 1937, when Alfred Cowles and Herbert Jones reviewed momentum in their paper “Some A Priori Probabilities in Stock Market Action.” In the 21st century, an inquiring reader can easily find hundreds of papers on the subject, most of it published in the wake of Jegadeesh and Titman’s seminal 1993 work: “Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market Efficiency,” which marks the launch of the modern age of momentum research.

I think his observation that momentum (relative strength to us) has been around since humans have been trading assets is spot on. It’s important to keep that in mind when thinking about why relative strength works—and why it has been immune to arbitrage. He writes:

Momentum, it seems, is one of the rare risk factors with features that elude so many other strategies: It’s persistent, conceptually straightforward, robust across asset classes, and relatively easy to implement. It’s hardly a silver bullet, but nothing else is either.

The only mystery: Why are we still talking about this factor in glowing terms? We still don’t have a good answer to explain why this anomaly hasn’t been arbitraged away, or why it’s unlikely to meet an untimely demise anytime soon.

Mr. Picerno raises a couple of important points here. Relative strength does have a lot of attractive features. The reason it is not a silver bullet is that it underperforms severely from time to time. Although that is also true of other strategies, I think the periodic underperformance is one of the reasons why the excess returns have not been arbitraged away.

Although he suggests we don’t have a good answer about why momentum works, I’d like to offer my explanation. I don’t know if it’s a good answer or not, but it’s what I’ve arrived at after years of research and working with relative strength portfolios—not to mention a degree in psychology and a couple of decades of seeing real investors operate in the market laboratory.

- Relative strength straddles both fundamental analysis and behavioral finance.

- High relative strength securities or assets are generally strong because they are undergoing fundamental improvement or are in a sweet spot for fundamentals. In other words, if oil prices are trending strongly higher, it’s not surprising that certain energy stocks are strong. That’s to be expected from the fundamentals. Often there is improvement at the margin, perhaps in revenue growth or operating margin—and that improvement is often underestimated by analysts. (Research shows that investors are more responsive to changes at the margin than to the absolute level of fundamental factors. For example, while Apple’s operating margin grew from 2.2% in 2003 to 37.4% in 2012, the stock performed beautifully. Even though the operating margin is expected to be in the 35% range this year—which is an extremely high level—the stock is getting punished. Valero’s stock price plummeted when margins went from 10.0% in 2006 to 2.4% in 2009, but has doubled off the low as margins rebounded to 4.8% in 2012. Apple’s operating margin on an absolute basis is drastically higher than Valero’s, but the delta is going the wrong way.) High P/E multiples can often be maintained as long as margin improvement continues, and relative strength tends to take advantage of that trend. Often these trends persist much longer than investors expect.

- From the behavioral finance side, social proof helps reinforce relative strength. Investors herd and they gravitate toward what is already in motion, and that reinforces the price movement. They are attracted to the popular and repelled by the unpopular.

- Periodic bouts of underperformance help keep the excess returns of relative strength high. When momentum goes the wrong way it can be ugly. Perhaps margins begin to contract and financial results are worse than analysts expect. The security has been rewarded with a high P/E multiple, which now begins to unwind. The herd of investors begins to stampede away, just as they piled in when things were going well. Momentum can be volatile and investors hate volatility. Stretches of underperformance are psychologically painful and the unwillingness to bear pain (or appropriately manage risk) discourages investors from arbitraging the excess returns away.

In short, I think there are multiple reasons why relative strength works and why it is difficult to arbitrage away the excess returns. Those reasons are both fundamental and behavioral and I suspect will defy easy categorization. Judging from my morning newspaper, human nature doesn’t change much. Until it does, markets are likely to work the same way they always have—and relative strength is likely to continue to be a powerful return factor.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Relative Strength Research, Thought Process | Tagged: behavioral finance, investor behavior, momentum, return factor, volatility |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Relative Strength Research, Thought Process | Tagged: behavioral finance, investor behavior, momentum, return factor, volatility |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

April 17, 2013

Here’s a link to a nice Nate Silver interview at Index Universe. Nate Silver is now a celebrity statistician due to his accurate election forecasts, although he started by doing statistics for baseball. In the interview, he discusses some of the ways that predictions can go wrong. In general, human beings are completely wrong about the stock market!

The typical retail investor frankly does things exactly wrong—they tend to buy at the top and sell at the bottom. Theoretically, you make this long-run average return, but a lot of people are buying at the market peaks. For many years, the Gallup Poll has periodically been asking investors whether it’s a good time to invest or not. There’s a strong historical negative correlation between when people think it’s a good time to invest and the five- or 10-year returns on the S&P 500.

Overconfidence can also kill predictions. Other studies have found that the more confident the forecaster the worse the forecast tends to be, something that makes watching articulate bulls and bears on CNBC particularly dangerous!

It’s worth a read.

2 Comments |

2 Comments |  Investor Behavior, Markets | Tagged: investor behavior, stock market |

Investor Behavior, Markets | Tagged: investor behavior, stock market |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

April 12, 2013

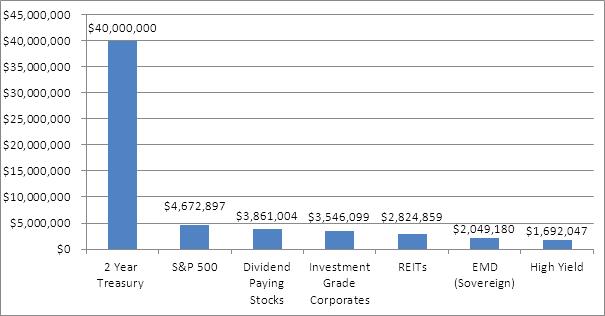

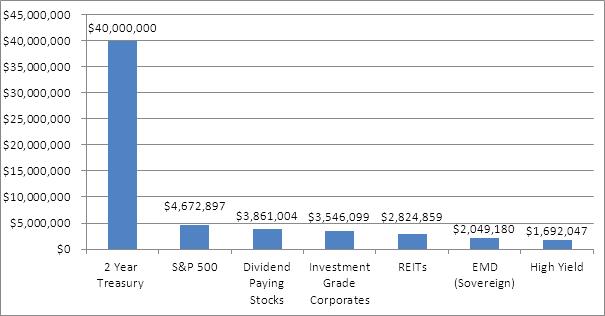

Investors lately are in a frenzy about current income. With interest rates so low, it’s tough for investors, especially those nearing or already in retirement, to come up with enough current income to live on. A recent article in Advisor Perspectives had a really interesting take on current income. The author constructed a chart to show how much money you would have to invest in various asset classes to “buy” $100,000 in income. Some of these asset classes might also be expected to produce capital gains and losses, but this chart is purely based on their current income generation ability. You can read the full original article to see exactly which asset classes were used, but the visual evidence is stunning.

Source: Advisor Perspectives/Pioneer Investments (click to enlarge)

There are two things that I think are important to recognize—and it’s hard not to with this chart.

- Short-term interest rates are incredibly low, especially for bonds presumed to have low credit risk. The days of rolling CDs or clipping a few bond coupons as an adequate supplement to Social Security are gone.

- In absolute terms, all of these amounts are relatively high. I can remember customers turning up their noses at 10% investment-grade tax-exempt bonds—they felt rates were sure to go higher—but it only takes a $1 million nest egg to generate a $100,000 income at that yield. Now, it would take more than $1.6 million, even if you were willing to pile 100% into junk bonds. (And we all know that more money has been lost reaching for yield than at the point of a gun.) A more realistic guess for the typical volatility tolerance of an average 60/40 balanced fund investor is probably something closer to $4.2 million. Even stocks aren’t super cheap, although they seem to be a bargain relative to short-term bonds.

That’s daunting math for the typical near-retiree. Getting anywhere close to that would require compounding significant savings for a long, long time—not to mention remarkable investment savvy. The typical advisor has only a handful of accounts that large, suggesting that much work remains to be done educating clients about savings, investment, and the reality of low current yields.

The pressure for current income might also entail some re-thinking of the entire investment process. Investors may need to focus more on total return, and realize that some capital gains can be spent as readily as dividends and interest. Relative strength may prove to be a useful discipline in the search for returns, wherever they may be found.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Retirement/Saving | Tagged: current income, relative strength, retirement, retirement income, savings |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Retirement/Saving | Tagged: current income, relative strength, retirement, retirement income, savings |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

April 12, 2013

Here we have the next round of the Dorsey, Wright Sentiment Survey, the first third-party sentiment poll. Participate to learn more about our Dorsey, Wright Polo Shirt raffle! Just follow the instructions after taking the poll, and we’ll enter you in the contest. Thanks to all our participants from last round.

As you know, when individuals self-report, they are always taller and more beautiful than when outside observers report their perceptions! Instead of asking individual investors to self-report whether they are bullish or bearish, we’d like financial advisors to weigh in and report on the actual behavior of clients. It’s two simple questions and will take no more than 20 seconds of your time. We’ll construct indicators from the data and report the results regularly on our blog–but we need your help to get a large statistical sample!

Click here to take Dorsey, Wright’s Client Sentiment Survey.

Contribute to the greater good! It’s painless, we promise.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

JP Lee

April 12, 2013

The Wall Street Journal had a small piece on Americans’ retirement readiness. In general, they’re not saving enough. Here’s an excerpt:

A separate study released today by investment firm Edward Jones finds that 79% of 1,008 U.S. adults surveyed in February said that they have committed a money mistake – and of those, 26% reported not having saved enough for retirement as their No. 1 problem. Also on the list: not paying attention to spending and making bad investments.

The EBRI research found that Americans are coming to grips with the dramatic improvements they need to make in their saving habits, with 20% of workers saying they need to save between 20 and 29% of their income to achieve a financially secure retirement, and 23% saying they need to save 30% – or more.

I added the bold. If you are a financial advisor, it’s really worth reading the entire EBRI research brief. It is absolutely eye-opening. You will discover that only 23% of workers ever obtained investment advice in the first place.

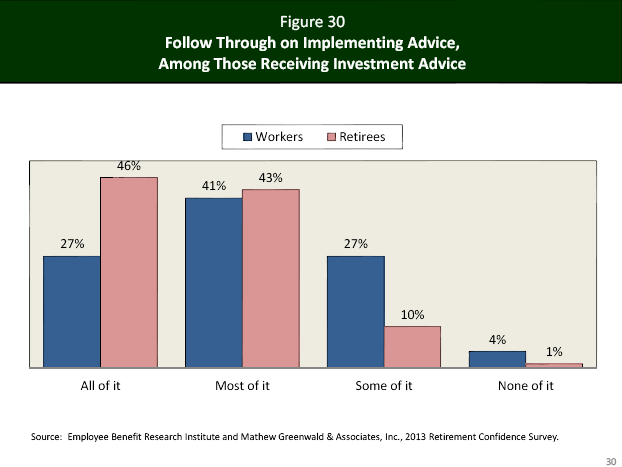

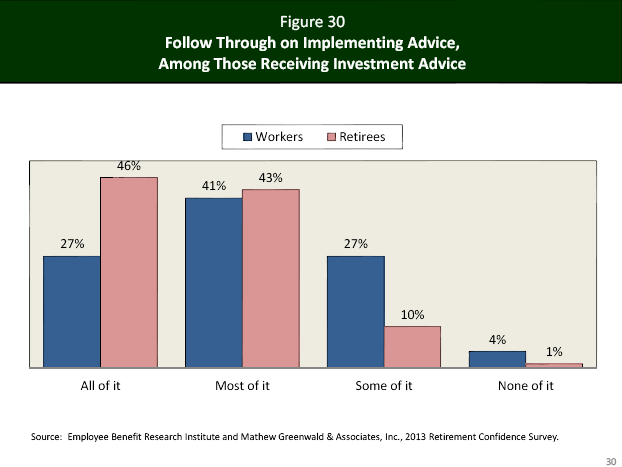

And, when they got advice, they ignored a lot of it! Here’s the graphic from EBRI on follow-through:

Only 27% fully implemented the advice. That makes about 6% of investors that got advice and followed it! (Elsewhere in the report, you will discover that a minority of investors have even tried to figure out what they might need in the way of retirement savings.) It seems obvious that you would have a large chance of falling short if you didn’t even have a goal.

As advisors, we often forget—as frustrated as we sometimes are with clients—that we are dealing with the cream of the crop. We work with investors who 1) have sought out professional advice and 2) follow all or most of it. We get cranky at anything less than 100% implementation, but many investors are doing less than that—if they bother to get advice at all.

So lighten up. Keep nudging your clients to save more, because you know it is their #1 problem. They might think you obnoxious, but they will thank you later. Help them construct a reasonable portfolio. And encourage them to get their friends and colleagues into some kind of planning and investment process. Their odds of success will be better if they get some help.

2 Comments |

2 Comments |  Investor Behavior, Wealth Management | Tagged: investor behavior, wealth management |

Investor Behavior, Wealth Management | Tagged: investor behavior, wealth management |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

April 4, 2013

I cringe every time I read an article by a value investor that says something like, “You should buy stocks that are on sale, just like you buy [pick your consumer item] on sale.” In the financial markets that can be dangerous.

In a great essay titled, I Want to Buy Losers, Clay Allen of Market Dynamics discusses the problems with this analogy. [You've got to read the whole essay to really appreciate it.]

Many investors buy stocks the way many consumers buy paper towels or any other staple. They are attracted to a sale and loss leaders are a proven method for a retailer to increase the traffic in their store. The value of the item is well known and a sale price gets the attention of potential buyers.

Mr. Allen explains brilliantly and succinctly why this analogy is bunk:

But stocks are not like paper towels. Paper towels can be used to satisfy a need and this is what gives the item its value to the consumer. What gives a stock its value? A stock cannot be used to satisfy a need or accomplish a task. The value of a stock is derived from the financial performance of the company, either actual or expected. The fact that the stock is down in price is usually a sure sign that the financial performance of the company is declining.

…if the value of the stock was constant, then buying bargain stocks would be the correct way to invest in stocks. But stock values are constantly changing as business conditions change for the company and the expectations of investors change.

All in all, it seems to me that relative strength often more closely reflects what the expectations of investors are–and the expectations are what counts. Let’s face it: strong stocks are usually strong because business conditions or fundamentals are good, and weak stocks are usually weak for a reason.

—-this article was originally published 3/26/2010. In the intervening years, my friend Clay Allen has passed away. His wisdom, however, is still with us. His point that a stock is not a paper towel is absolutely correct. The only purpose of an equity investment is to make money.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  From the Archives, Investor Behavior, Thought Process | Tagged: investor behavior |

From the Archives, Investor Behavior, Thought Process | Tagged: investor behavior |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

April 4, 2013

Mutual fund flow estimates are derived from data collected by The Investment Company Institute covering more than 95 percent of industry assets and are adjusted to represent industry totals.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets |

Investor Behavior, Markets |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

JP Lee

April 1, 2013

Our latest sentiment survey was open from 3/22/13 to 3/29/13. The Dorsey, Wright Polo Shirt Raffle continues to drive advisor participation, and we greatly appreciate your support! This round, we had 72 advisors participate in the survey. If you believe, as we do, that markets are driven by supply and demand, client behavior is important. We’re not asking what you think of the market—since most of our blog readers are financial advisors, we’re asking instead about the behavior of your clients. Then we’re aggregating responses exclusively for our readership. Your privacy will not be compromised in any way.

After the first 30 or so responses, the established pattern was simply magnified, so we are fairly comfortable about the statistical validity of our sample. Some statistical uncertainty this round comes from the fact that we only had four investors say that thier clients are more afraid of missing a stock upturn than being caught in a downdraft. Most of the responses were from the U.S., but we also had multiple advisors respond from at least two other countries. Let’s get down to an analysis of the data! Note: You can click on any of the charts to enlarge them.

Question 1. Based on their behavior, are your clients currently more afraid of: a) getting caught in a stock market downdraft, or b) missing a stock market upturn?

Chart 1: Greatest Fear. From survey to survey, the S&P 500 was flat, and our indicators were mixed. The fear of downdraft group ticked up a point, from 70% to 71%. The downdraft group fell from 30% to 29%.

Chart 2: Greatest Fear Spread. Another way to look at this data is to examine the spread between the two groups. The spread rose from 41% to 42%.

Question 2. Based on their behavior, how would you rate your clients’ current appetite for risk?

Chart 3: Average Risk Appetite. Average risk appetite jumped this round, from 2.95 to 3.08, matching the all-time survey highs for this indicator.

Chart 4: Risk Appetite Bell Curve. This chart uses a bell curve to break out the percentage of respondents at each risk appetite level. This round, there’s been a noticeable shift towards 3. Nearly half of all participants want a risk appetite of 3.

Chart 5: Risk appetite Bell Curve by Group. The next three charts use cross-sectional data. The chat plots the reported client risk appetite separately for the fear of downdraft and for the fear of missing upturn groups. We can see the upturn group wants more risk, while the fear of downturn group is looking for less risk.

Chart 6: Average Risk Appetite by Group. This round, the downturn group’s average rise, while the upturn group’s average fell slightly.

Chart 7: Risk Appetite Spread. This is a chart constructed from the data in Chart 6, where the average risk appetite of the downdraft group is subtracted from the average risk appetite of the missing upturn group. The spread dropped this round.

From survey to survey, the S&P was basically flat. The overall risk appetite number is sitting at all-time highs. We can expect to see it break through if the market can continue to rally. The first quarter was great for the stock market, so here’s hoping to more of the same.

No one can predict the future, as we all know, so instead of prognosticating, we will sit back and enjoy the ride. A rigorously tested, systematic investment process provides a great deal of comfort for clients during these types of fearful, highly uncertain market environments. Until next time, good trading and thank you for participating.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

JP Lee

March 25, 2013

Morningstar has a market-beating strategy call “Buy the Unloved” that they update from time to time. Essentially, it consists of buying the fund categories with the most outflows and holding on to them for three years, on the theory that retail investors generally get things wrong. Sadly, “Buy the Unloved” has a good track record, indicating that their thesis is largely correct!

Here are a couple of key excerpts from their 2013 update on the Buy the Unloved strategy:

Morningstar has followed this strategy since the early 1990s, using annual net cash flows to identify each year’s three most unloved and loved equity categories, which feed into two separate portfolios (unloved and loved). We track the average returns for those categories for the subsequent three years, adding in new categories each year and swapping out categories after three years are up. We’ve found that holding a portfolio of the three most unpopular equity categories for at least three years is an effective approach: From 1993 through 2012, the “unloved” strategy gained 8.4% annualized to the “loved” strategy’s 5.1% annualized. The unloved strategy has also beaten the MSCI World Index’s 6.9% annualized gain and has slightly beat the Morningstar US Market Index’s 8.3% return.

According to Morningstar fund flow data, the most popular equity categories in 2012 were diversified emerging markets (inflows of $23.2 billion), foreign large value (inflows of $4.6 billion), and real estate (inflows of $3.8 billion). Those looking across asset classes might want to be cautious on sending new money to intermediate-term bond (inflows of $112.3 billion), short-term bond (inflows of $37.6 billion), and high-yield bond (inflows of $23.6 billion), particularly as interest rates have nowhere to go but up.

The most unloved equity categories are also the most unpopular overall: large growth (outflows of $39.5 billion), large value (outflows of $16 billion), and large blend (outflows of $14.4 billion). These categories have seen outflows despite posting double-digit gains in 2012. The money leaving from these categories reflects a broader trend of investors fleeing equity funds while piling into fixed-income offerings and passive ETFs.

Now that we are almost a full quarter into 2013, it might be worthwhile to think about what we have seen so far this year: good performance from large-cap equities and sluggish performance from bonds.

Morningstar should get a public service award for publishing this data—and it’s worth thinking about what you can learn from it. The most popular investment trends are not always the profitable ones. In fact, their work indicates that it could be valuable to spend time thinking about going into areas that are currently unpopular. Obviously, this does not need to be used (and probably shouldn’t be) as a stand-alone strategy, but it might be useful as a guide to portfolio adjustments.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: behavioral finance, contrary opinion, investor behavior |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: behavioral finance, contrary opinion, investor behavior |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

March 22, 2013

Here we have the next round of the Dorsey, Wright Sentiment Survey, the first third-party sentiment poll. Participate to learn more about our Dorsey, Wright Polo Shirt raffle! Just follow the instructions after taking the poll, and we’ll enter you in the contest. Thanks to all our participants from last round.

As you know, when individuals self-report, they are always taller and more beautiful than when outside observers report their perceptions! Instead of asking individual investors to self-report whether they are bullish or bearish, we’d like financial advisors to weigh in and report on the actual behavior of clients. It’s two simple questions and will take no more than 20 seconds of your time. We’ll construct indicators from the data and report the results regularly on our blog–but we need your help to get a large statistical sample!

Click here to take Dorsey, Wright’s Client Sentiment Survey.

Contribute to the greater good! It’s painless, we promise.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Sentiment |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

JP Lee

March 20, 2013

AdvisorOne ran an interesting article recently, reporting the results of a retirement study done by Franklin Templeton. Investors are feeling a lot of stress about retirement, even early on. And given how things are going for many of them, feeling retirement stress is probably the appropriate response! In no particular order, here are some of the findings:

A new survey from Franklin Templeton finds that nearly three-quarters (73%) of Americans report thinking about retirement saving and investing to be a source of stress and anxiety.

In contrast to those making financial sacrifices to save, three in 10 American adults have not started saving for retirement. The survey notes it’s not just young adults who are lacking in savings; 68% of those aged 45 to 54 and half of those aged 55 to 64 have $100,000 or less in retirement savings.

…two-thirds (67%) of pre-retirees indicated they were willing to make financial sacrifices now in order to live better in retirement.

“The findings reveal that the pressures of saving for retirement are felt much earlier than you might expect. Some people begin feeling the weight of affording retirement as early as 30 years before they reach that phase of their life,” Michael Doshier, vice president of retirement marketing for Franklin Templeton Investments, said in a statement. “Very telling, those who have never worked with a financial advisor are more than three times as likely to indicate a significant degree of stress and anxiety about their retirement savings as those who currently work with an advisor.”

As advisors, we need to keep in mind that our clients are often very anxious over money issues or feel a lot of retirement stress. We often labor over the math in the retirement income plan and neglect to think about how the client is feeling about things—especially new clients or prospects. (Of course, they do feel much better when the math works!)

The silver lining, to me, was that most pre-retirees were willing to work to improve their retirement readiness—and that those already working with an advisor felt much less retirement stress. I don’t know if clients of advisors are better off for simply working with an advisor (other studies suggest they are), but perhaps even having a roadmap would relieve a great deal of stress. As in most things, the unknown makes us anxious. Working with a qualified advisor might make things seem much more manageable.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Retirement/Saving | Tagged: factor investing, investor behavior, retirement, retirement income |

Investor Behavior, Retirement/Saving | Tagged: factor investing, investor behavior, retirement, retirement income |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody