Durable portfolio construction comes from diversification, but diversification can mean a lot of different things. Most investors, unfortunately, give portfolio construction very little thought. As a result, their portfolios are not durable. In fact, they tend to come unglued during every downturn. Why does that happen?

I think there are a couple of inter-related problems.

- Volatility tends to increase during downturns

- Certain correlations tend to increase during declines

Volatility is an artifact of uncertainty. Once a downturn starts, no one is sure where the bottom is. That uncertainty often creates selling, which may cause the market to decline, which in turn may create more selling. We’ve all seen this happen. Eventually there is capitulation and the market bottoms, but it can be quite frightening in the middle of the move when no one knows where the bottom will be.

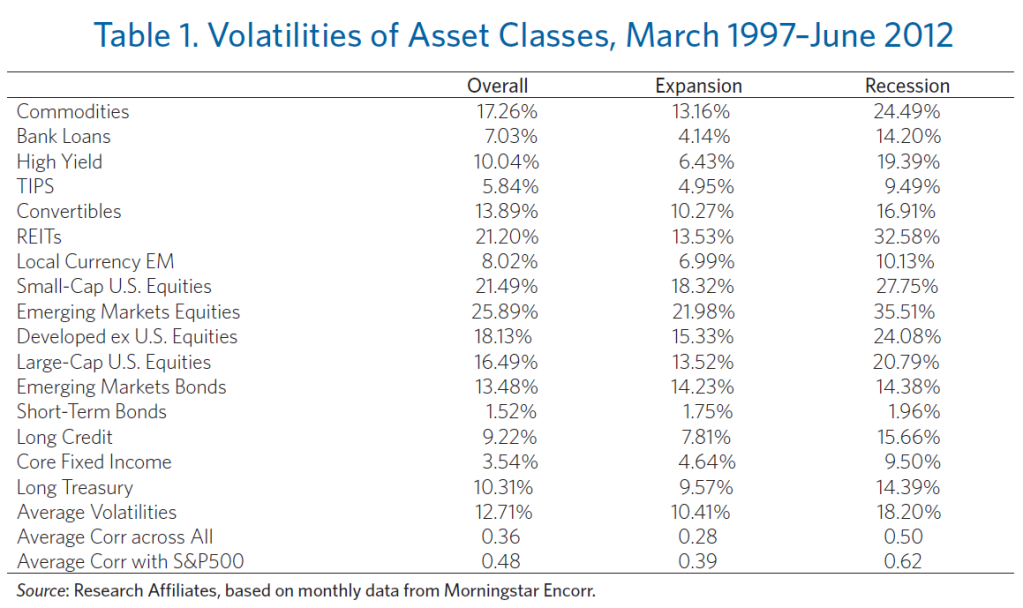

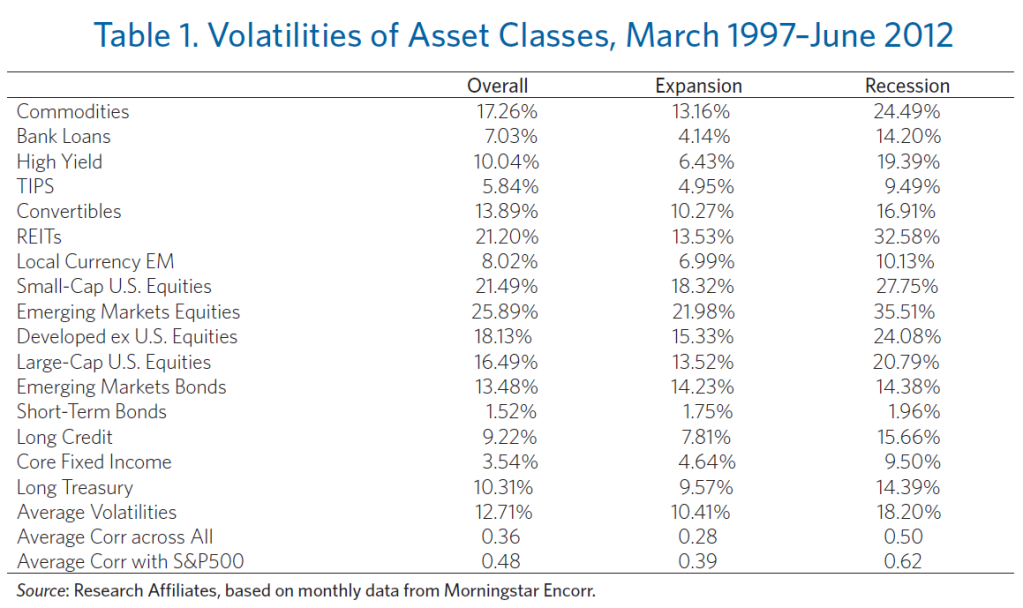

Research Affiliates had a recent article on diversification, and included in it was a table that showed the change in volatility that accompanied recessions. The bump is typically pretty large.

Source: Research Affiliates, via RealClearMarkets (click to enlarge image)

In general, riskier assets had the biggest jumps in volatility when the economy was under pressure. Thus, it makes perfect sense how a relatively sedate portfolio under typical conditions becomes much more volatile when conditions are tough.

Correlations are also observed to rise during declines. ”Risk on” assets, especially, often have rising correlations among themselves as risk is shunned. Similarly, “risk off” assets may see their internal correlations rise. However, it may be the case that correlations between dissimilar asset classes don’t change nearly as much. In other words, risk-on and risk-off assets might not have rising correlations during a period of market stress. In fact, it wouldn’t be surprising to see those correlations actually fall. So, one way to make portfolios more durable is to diversify by volatility.

There are probably multiple ways to do this. You could use volatility buckets for low-volatility assets like bonds and high-volatility assets like stocks. Or, you could just make sure that your portfolios have exposure to a broad range of asset classes, including asset classes with different responses to market stress.

Within an individual asset class, you are likely to see rising correlations between members of your investment universe. For example, during a sharp market decline, you’re likely to see increasing correlations among stocks. However, it’s possible to think about diversifying by return factor within an asset class.

AQR and others have shown, for example, that the excess returns of value and relative strength stocks are uncorrelated. That means that years where relative strength outperforms the market are likely to be years when value lags, and vice versa. Both types of stocks might go up in a rising market or fall in a declining market, but they will likely have different performance profiles. Diversifying by using complementary strategies is another way to make portfolios more durable.

As Research Affiliates points out, simple diversification is not a panacea. As their table shows, almost every asset class (possible exception: short-term bonds) has higher volatility in a bad economy.

Durable portfolio construction, then, might consist of multiple forms of diversification:

- diversification by volatility

- diversification by asset class

- diversification by strategy

While there might be rising correlations between some types of assets, you are also likely to see falling correlations between others. Although the entire portfolio might have an elevated level of volatility, an absence of surging cross-correlations might make tail events a little more manageable. Good portfolio construction obviously won’t eliminate market risk, but it might make regular market volatility a little more palatable for a broad range of investors.