November 14, 2012

Nervous energy is a great destroyer of wealth.—-Fayez Sarofim

This quote was embedded in an article written by Jim Goff, the research director at Janus. Along with making the case for equities, he talks about how important it is to have a reasonable allocation that you can stick with—and then to leave it alone.

Mr. Goff talks about the way in which many investors undermine their returns:

The average investor is far from contrarian. I remember vividly when a strategist from a top-tier investment firm in the mid-1990’s told me that while the S&P 500 had grown at 13% per year over the prior 10 years, the realized equity returns of his firm’s retail client base, on average, had compounded at only 5% per year. The S&P would have turned $100,000 into $339,000 during that period, but their average investor ended with $163,000.

Often this is caused by jumping in and out of an asset class, rather than by making tactical adjustments within the asset class. There’s nothing wrong with tactical asset allocation as long as it’s done systematically. Even a lousy version of strategic asset allocation—carried out effectively—will probably beat what most investors are doing! Either way, undisciplined fiddling often ruins investment results. Mr. Sarofim’s quote is something to take to heart.

There are a couple of points relevant to portfolio management.

- Think about a reasonable asset allocation for your situation, one you can stick with.

- Have a systematic process for making portfolio adjustments, not one that is undisciplined and responsive to the news environment.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Investor Behavior, Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process | Tagged: asset allocation, investor behavior, Tactical Asset Allocation |

Investor Behavior, Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process | Tagged: asset allocation, investor behavior, Tactical Asset Allocation |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

November 13, 2012

NPR’s Tess Vigeland on why financial advisers are needed now more than ever:

The system today demands so many more financial choices from all of us. We have to manage our own retirement accounts. We have to save enormous sums for college. We pay a far bigger chunk of our health care bills. We’re really on our own — and we’re terrified we’re not going to have enough. So we take risks with our money that we probably shouldn’t.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Thought Process, Wealth Management |

Thought Process, Wealth Management |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Andy Hyer

November 9, 2012

You don’t know jack about what the market is going to do. Neither do I. None of us really do. Falling back on investment process is the only way to survive in the long run. Bob Seawright of Above the Market has a great commentary on investment process and randomness:

In what [Daniel] Kahneman calls the “planning fallacy,” our ability even to forecast the future, much less control the future, is extremely limited and is far more limited than we want to believe. In his terrific book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman describes the “planning fallacy” as a corollary to optimism bias (think Lake Wobegon – where all the children are above average) and self-serving bias (where the good stuff is my doing and the bad stuff is always someone else’s fault). Most of us overrate our own capacities and exaggerate our abilities to shape the future. The planning fallacy is our tendency to underestimate the time, costs, and risks of future actions and at the same time overestimate the benefits thereof. It’s at least partly why we underestimate bad results. It’s why we think it won’t take us as long to accomplish something as it does. It’s why projects tend to cost more than we expect. It’s why the results we achieve aren’t as good as we expect. It’s why I take three trips to Home Depot on Saturdays. We are all susceptible – clients and financial professionals alike.

As a consequence, in all probabilistic fields, the best performers dwell on process. This is true for great value investors, great poker players, and great athletes. A great hitter focuses upon a good approach, his mechanics, being selective and hitting the ball hard. If he does that – maintains a good process – he will make outs sometimes (even when he hits the ball hard) but the hits will take care of themselves. Maintaining good process is really hard to do psychologically, emotionally, and organizationally. But it is absolutely imperative for investment success.

I flipped Mr. Seawright’s paragraphs around, but that’s just how I think. The emphasis is mine, but I think Mr. Seawright is correct about all of this. We are often attracted by shiny things, by the hedge fund manager that had the big hit last year, but the real winners are the investors with a great process that they stick with through thick and thin. Those investors often sustain good track records for decades. Maintaining good process is really hard to do, but the rewards over time make it worth the effort.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  From the MM, Thought Process |

From the MM, Thought Process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

November 8, 2012

As much as investors appear to dislike stocks right now, Bob Carey of First Trust points out that the S&P has a habit of bouncing back. The gist of his argument is contained in a nice graphic and a few paragraphs of commentary. Here’s the relevant chart:

Source: Bob Carey, First Trust (click on image to enlarge)

Although this picture is probably worth a thousand words too, his commentary is especially on point. Here’s what you are looking at:

- The time periods featured in the chart depict the annualized returns for the S&P 500 from the index’s lowest price point following a crisis situation.

- Those crisis situations were as follows: 1973-74 (Oil Embargo); 1981 (Hyperinflation); 1987 (Crash/Black Monday); 1990 (S&L Failures/LBOs); 2002 (Internet Bubble Burst); and 2008 (Subprime/Financial Crisis).

Amazing, isn’t it? If you had the nerve to buy during each crisis, you racked up big returns over the long run. (The recent returns have been exceptionally strong, but the time period is much shorter and hasn’t had time to include any additional bear markets.)

I find it extraordinary that the market managed 8% annual returns if you bought after the tech wreck in 2002, even after holding it all the way through the most recent financial crisis. American business is remarkably resilient and our financial markets reflect that. Even at the depths of a crisis—especially at the depths of a crisis—it makes sense of buy shares in growing businesses. Headlines and negative investor sentiment shouldn’t necessarily deter you from buying productive assets.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: equities, stock market |

Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: equities, stock market |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

November 6, 2012

Occasionally, when we buy a given stock in our portfolios there is grumbling around the office…’I can’t believe we’re buying this…’ AOL was one of those stocks. Everyone knows that AOL’s days are over, right? Subscription revenue has been falling for years. Yet, for some reason, it had incredibly strong relative strength.

Source: Yahoo! Finance

From today’s WSJ comes a clue as to where its improving fundamentals are coming from:

AOL Inc.’s revenue held flat in the third quarter, marking the first time in seven years the Internet company didn’t see a decline, despite a decrease in its core business of selling display advertising.

AOL also swung to a net profit of $20.8 million in the quarter.

Advertising revenue grew 7%, offsetting declines in subscription revenue for the first time since CEO Tim Armstrong took the reins in 2009 with a plan to turn the aging Internet-access icon into an advertising-driven online media company.

But the growth was due to increases in international display as well as search advertising and revenue from the company’s third-party ad network. Revenue from domestic display fell 3%, dragging down overall display revenue by 1%.

“Our domestic display results are not as robust as we would like, and we are going to improve them over time,” Mr. Armstrong said on a conference call with analysts.

In an interview, Mr. Armstrong said the company hoped to boost domestic display advertising by increasing traffic to AOL-branded properties like the Huffington Post and Patch and migrating advertisers from low-growth inventory like traditional banner ads toward more premium advertising inventory like video.

Noting the company’s “dual strategy” of going after both the high and low ends of the online advertising market, he also said the company hopes to benefit from what he expects to be significant growth in programmatic ad buying—or automated buying of ads through digital platforms like exchanges—next year. Mr. Armstrong expects programmatic ad buying to rise from 7% of the overall ad market to a double-digit percentage.

He also predicted that more marketers would move some of their TV ad budgets to digital next year. AOL has made a big bet on video this year, launching the AOL On video network and the HuffPost Live streaming channel.

Just because it wasn’t clear to me at the time we were buying it that the fundamentals of AOL were improving doesn’t mean that others didn’t know. Obviously, some did and were actively buying. Relying on relative strength negates the need to be a fundamental expert on every available security in the marketplace; relative strength just identifies the strongest trends and provides the framework for capitalizing on those trends.

Dorsey Wright currently owns AOL. A list of all holdings or the trailing 12 months is available upon request.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Markets, Thought Process |

Markets, Thought Process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Andy Hyer

November 5, 2012

I find the chart below to be incredibly bullish. The last two times that the 10-year annualized returns of the U.S. stock market were negative were followed by decades of strong equity returns. The returns over the past couple of years are suggesting that we are on a similar course this time as well. Something to think about as retail investors continue to pile into bonds.

Source: Vanguard

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Markets, Thought Process |

Markets, Thought Process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Andy Hyer

November 1, 2012

A recent article at AdvisorOne suggests that CNBC is detrimental to the well-being of your clients. In truth, it didn’t really single out CNBC. It was applicable to any steady diet of financial news. Here’s what the article had to say about financial news and client stress:

Clients get stressed by things you wouldn’t predict. This is a classic example, uncovered at the Kansas State University (KSU) Financial Planning Research Center by Dr. Sonya Britt of KSU and Dr. John Grable, now at the University of Georgia, in their recent paper “Financial News and Client Stress.” They found that contrary to what you might think, client stress goes up when watching financial news, and hearing that the market went up causes stress levels to rise even higher. “Specifically, 67% of people watching four minutes of CNBC, Bloomberg, Fox Business News and CNN showed increased stress, while 75% of those who watched a positive-only news video exhibited an increase in stress,” they wrote.

Why? “Financial news was found to increase stress levels, particularly among men,” wrote Grable and Britt. Surprisingly, positive financial news, like reports of bullishness in the stock market, created the highest levels of stress, they found, suggesting that positive financial news may trigger regret among some people. The authors referred to previous studies of regret that found “people tend to feel most remorseful when they look back at a situation and realize that they failed to take action.” The authors’ conclusion: Financial advisors should think twice about having office TVs tuned to financial channels.

Surprising, isn’t it, to find out that clients were stressed even when the market was going up? The ups and downs of the market appear to elicit client’s concerns about their financial decisions. Anything that undermines their confidence is probably not a positive. In fact, one of the important things advisors can do is help clients manage their investment behavior. Financial news appears to work at cross-purposes to that. (Other things do too; the full article has a host of useful thoughts on what stresses clients and how to reduce client stress.)

The relationship between high levels of stress and poor decision-making is well-known to psychologists, researchers and sports fans around the world. “Our brains operate on different levels, depending on circumstances,” Britt told me in an interview. “Under high levels of stress, our intellectual decision-making functions shut down, and our emotional flight or fight response kicks in.” Added Grable: “People will adapt to low levels of stress differently, but overwhelming stress results in predictable behavior. When we are stressed, our brains cannot move to make intellectual decisions.”

If we want to help our clients stay calm and stick with their plan, maybe we should ask about their family, their pets, and their hobbies in a relaxed setting rather than inundating them with market data.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Investor Behavior, Just for Fun, Thought Process, Wealth Management | Tagged: CNBC, investor behavior, wealth management |

Investor Behavior, Just for Fun, Thought Process, Wealth Management | Tagged: CNBC, investor behavior, wealth management |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 31, 2012

Did you know that Japan made up approximately 60% of the MSCI EAFE Index in 1989? It’s true. Even today, Japan makes up about 20 percent of the MSCI EAFE Index. The horror show for Japanese equities since its 1989 peak is shown below:

Source: Yahoo! Finance

Relative strength strategies are often known for their ability to own the strong areas of the market, but just as important as what you own is what you don’t own. Current exposure to Japan in the PowerShares DWA Developed Markets Technical Leaders ETF (PIZ) is shown below:

Japan is currently our biggest underweight.

See www.powershares.com for more details.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Markets, Portfolio Theory, Thought Process |

Markets, Portfolio Theory, Thought Process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Andy Hyer

October 31, 2012

We’ve written before about beanbag economics, the tendency of the world to adapt. When you smush down a beanbag chair in one area, it simply adapts by poofing out somewhere else. The global economy is no different.

Consider the beanbag economics at work in the following excerpt of an article on the bond market in the Financial Times:

Central bankers around the world have followed the lead of the Fed in forcing down interest rates in the hope of boosting economic recovery.

This has presented a dilemma for income investors, who can maintain previous levels of yield only by buying riskier or longer dated bonds.

For companies, though, it has been an unalloyed boon. Corporate treasurers have rushed to sell bonds, refinancing existing loans and expiring bonds with longer term debt paying low, fixed interest rates.

I put the relevant part in bold. Sure, low interest rates are tough on savers and bond buyers—but they’ve been great for companies. The full article points out that new corporate debt issuance has already hit a record this year, with a couple of months still to go. Some companies have been able to retire old debt and refinance it at very low rates.

From an investment point of view, the upside is that earnings leverage will be much more powerful. The drag from debt service will be much lower for companies that have been able to reduce their interest costs.

Thinking about global economics in terms of a beanbag can help underscore the idea that opportunities are always present. In a global economy, one sector’s loss may be another’s gain. Tracking the relative strength of a broad range of asset classes can help investors identify where those investment opportunities are.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Markets, Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process |

Markets, Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 26, 2012

Martjin Cremers, a professor at Yale, and his colleague, Antti Petajisto, authored a paper on the concept of active share. Advisor Perspectives recently interviewed Mr. Cremers to ask about his research. (This link is worth checking out, as it has links to additional articles such as From Yale University: New Research Confirms the Value of Active Management and Compelling Evidence That Active Management Really Works.)

Active share is a holdings-based measure of how different the holdings in an active portfolio are from the benchmark portfolio. As an example, an S&P 500 index fund would have an active share of 0%, since the holdings would be identical to the benchmark. Portfolios with low active shares around 20-60% are still so close to the benchmark that they are considered closet indexers.

Where Cremers and Petajisto differ from the establishment is that by segmenting managers in this way, they believe they are able to identify a subset of managers–those with high active share–who can outperform the benchmark over time.

That result is probably the most controversial. We find significant evidence, in our view, that a lot of managers actually do have some skill.

What I find refreshing about their approach is their willingness to examine aggregate data more thoroughly. In aggregate, their data also shows that fund managers do not outperform the benchmark. Most studies stop there, pretend not to notice that numerous tested factors show evidence of long-term outperformance, and then advise investors to buy index funds and to forget about active management.

Cremers and Petajisto were not content to take the lazy road. And, in fact, when looked at in more granular fashion, the data tells a different story. Closet indexers do worse than the market, but many managers with high active share show evidence of skill. This is much more in accord with other academic research that shows that broad, robust factors like relative strength and deep value can outperform over time. A manager that pursued such a strategy would have high active share and would have a good chance of long-term outperformance. That’s exactly what our systematic relative strength strategies are designed to do.

—-this article originally appeared 2/10/2010. Last week, another well-known pundit was advancing the results of their study, which showed that managers do not outperform the market. They also took the lazy road, claiming that investors should just buy index funds. The truth is more nuanced, as Cremers and Petajisto show. There are several tested return factors that show long-term outperformance, such as value and relative strength. Managers pursuing a factor-based strategy would be likely to have high active share, and according to Cremers and Petajisto, might be just the type of manager that shows evidence of significant skill.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Markets, Relative Strength Research, Thought Process | Tagged: active share, relative strength |

Markets, Relative Strength Research, Thought Process | Tagged: active share, relative strength |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 25, 2012

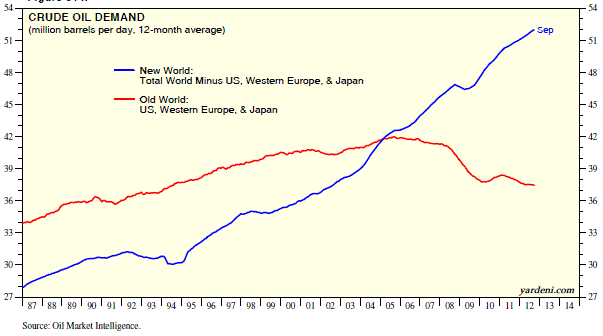

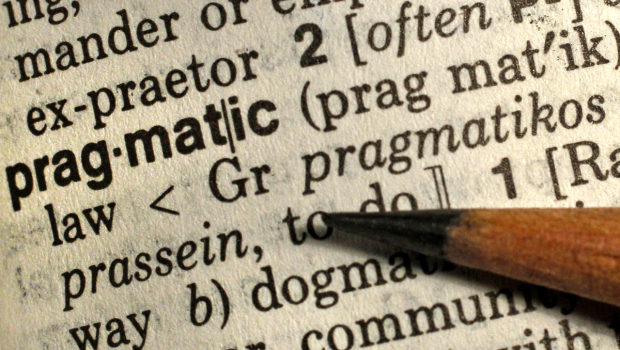

Ed Yardeni of Dr. Ed’s Blog had an interesting chart of oil demand. The interesting part was that he segmented the demand between Old World (US, Western Europe, and Japan) and New World (everyone else). There really is a new world order, something that your portfolio needs to reflect.

Source: Dr. Ed’s Blog (click on image to enlarge)

In this case, a picture might be worth a few thousand words. You can see pretty clearly that the growth rate in oil demand is far higher outside the Old World. Up until 2004, aggregate demand was higher in the Old World, but that has changed too. The big engine of oil demand is no longer the large developed economies. The last recession created a downturn in oil demand in the Old World, but created barely a blip on the chart for the New World. I was surprised when I saw this chart, and I’m probably not the only one. I think most people in the investment industry would be surprised by this—and certainly many clients would be too.

To me, this is a good argument for global tactical asset allocation. Yes, the economy is slow—but clearly not everywhere. Based on oil demand, some economies are growing just fine. Global tactical asset allocation allows you to go where the returns are, regardless of where they may be. Relative strength is a good way to locate those returns.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Markets, Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process | Tagged: global tactical asset allocation, oil, Tactical Asset Allocation |

Markets, Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process | Tagged: global tactical asset allocation, oil, Tactical Asset Allocation |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 22, 2012

No strategy can make up for inadequate savings or premature retirement.—-Rob Arnott, Research Affiliates

I like this quote a lot. It gets at some of the factors that allow clients to achieve wealth, along with intelligent investment management.

- Savings, and

- Time.

Savings is usually more important than investment strategy, especially when a client is just beginning to accumulate capital. Without some savings to begin with, there’s no capital to manage.

Time is important to allow compounding to occur. This is often lost on young investors, who sometimes do not realize what a jump they will get by starting a portfolio early. How many of us in the industry have met with the 55-year-old client who has just finished putting the kids through college and is now ready to start saving for retirement—only to realize they will need to save 115% of their current income to reach the retirement goal they have in mind? Oops.

Save early and often, and give your capital lots of time to grow.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Retirement/Saving, Thought Process | Tagged: compounding, savings, strategy |

Retirement/Saving, Thought Process | Tagged: compounding, savings, strategy |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 19, 2012

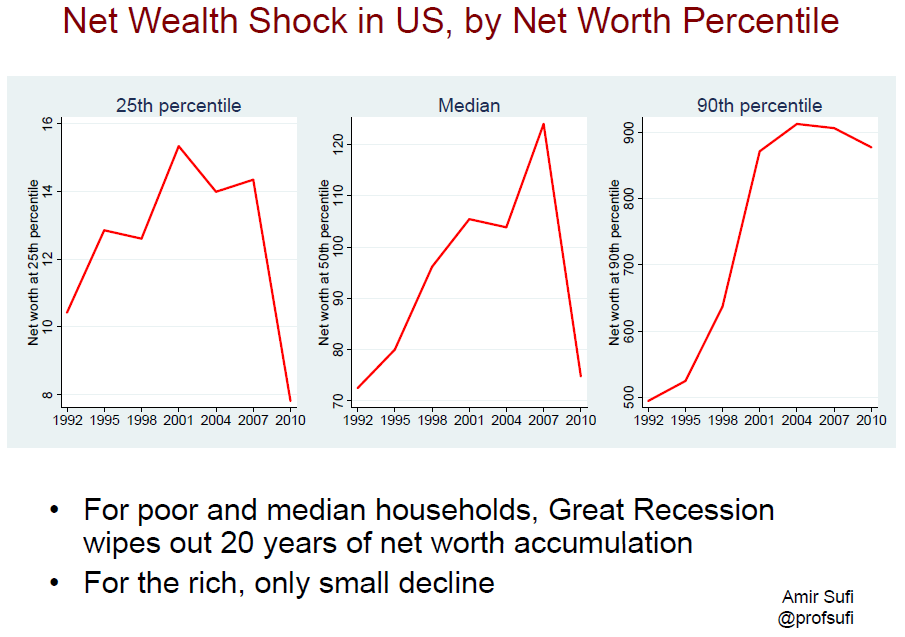

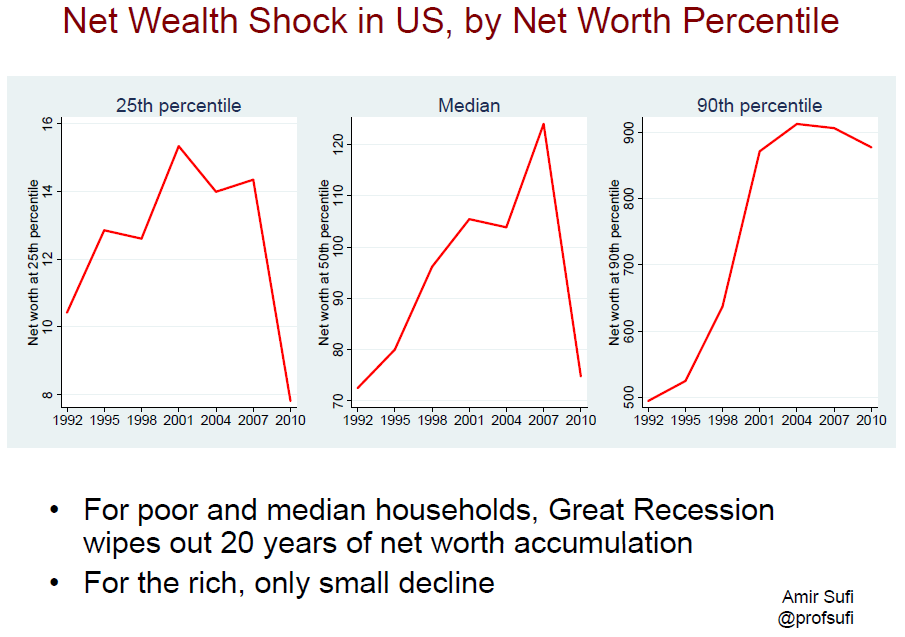

Professor Amir Sufi (University of Chicago Booth School of Business) is an interesting researcher. He recently tweeted a picture of what he called “net wealth shock” to show how the recession had affected various families. It’s reproduced below, but in effect, it shows that low and median net worth families have had a large negative impact from the recession while high net worth families have been impacted much less. I think portfolio diversification has everything to do with it.

The Effect of Buying One Stock on Margin

Source: Amir Sufi (click on image to enlarge)

For clues to why this happened, consider an earlier paper that Dr. Sufi co-wrote on household balance sheets. I’ve linked to the entire paper here (you should read it for insight into very clever experimental design), but here’s the front end of the abstract:

The large accumulation of household debt prior to the recession in combination with the decline in house prices has been the primary explanation for the onset, severity, and length of the subsequent consumption collapse.

Later in the paper, he reiterates that it is the combination of these two things that is deadly.

The household balance sheet shock in high leverage counties came from two sources: high ex ante debt levels and a large decline in house prices. One natural question to ask is: could the decline in house prices alone explain the collapse in consumption in these areas?

Our answer to this question is a definitive no-it was the combination of house price declines and high debt levels that drove the consumption decline.

And he and his co-authors, through clever data analysis, proceed to explain why they believe that to be the case.

Now consider what this is saying from a portfolio management point of view: why was the impact of falling home prices so devastating to low and median net worth households?

The negative impact came primarily from lack of diversification. Low and median net worth households had essentially one stock on margin. I know people don’t think they are buying their house on margin, but the net effect of a home loan—magnifying gains and losses—is the same. When that stock (their house) went south, their net worth went right along with it.

High net worth households were simply better diversified. It’s not that their houses didn’t decline in value also; it’s just that their house was not their only asset. In addition, they were less leveraged.

There are probably a couple of things to take away from this.

- Diversify broadly. It’s no fun to have everything in one asset when things go wrong, whether it’s your house or Enron stock in your pension plan.

- Debt kills. Having a single asset that nosedives is bad, but having it on margin is disastrous. There’s no room for error with leverage—and no way to wait things out.

Perhaps high net worth families are more diversified simply because they have greater wealth. Maybe they took the same path as everyone else and just got lucky not to have a recession in the middle of their journey. However, I think it’s also worth contemplating the converse: maybe those families achieved greater wealth because they diversified more broadly and opted to use less leverage.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  From the MM, Investor Behavior, Markets, Portfolio Theory, Thought Process, Wealth Management | Tagged: diversification, portfolio management |

From the MM, Investor Behavior, Markets, Portfolio Theory, Thought Process, Wealth Management | Tagged: diversification, portfolio management |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 18, 2012

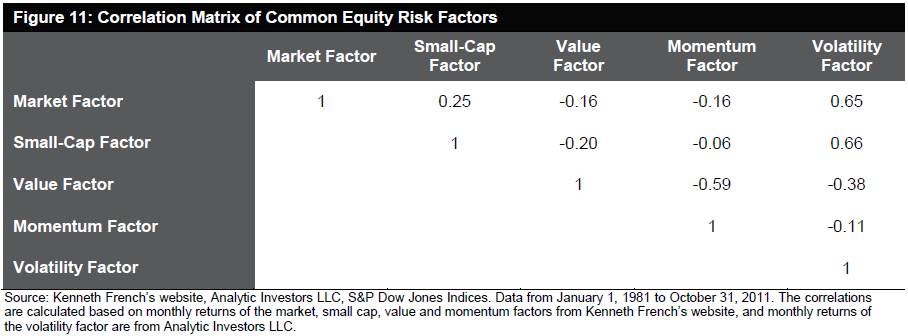

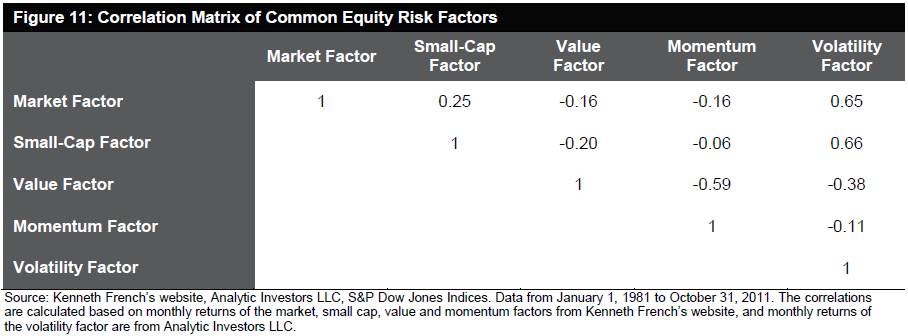

We use relative strength (known as “momentum” to academics) in our investment process. We’ve written extensively how complementary strategies like low volatility and value can be used alongside relative strength in a portfolio. S&P is now on board the train, as they show in this research paper how alternative beta strategies are often negatively correlated. In fact, here’s the correlation matrix from the paper:

Source: Standard & Poors (click to enlarge image)

You can see that relative strength/momentum is negatively correlated with both value and low volatility. This is why we prefer diversification through complementary strategies.

They conclude:

…combining alternative beta strategies that are driven by distinct sets of risk factors may help to reduce the active risk and improve the information ratio.

Diversification is important for portfolios, but it’s not easily achieved. For example, if you decide to segment the market by style box rather than by return factors, you will find that the style boxes are all fairly correlated. Although it’s a mathematical truism that anything that isn’t 100% correlated will help diversification, diversification is far more efficient when correlations are low or negative.

We think using factor returns to identify complementary strategies is one of the more effective keys to diversification.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Markets, Portfolio Theory, Thought Process | Tagged: diversification, portfolio theory, relative strength, return factors, strategies |

Markets, Portfolio Theory, Thought Process | Tagged: diversification, portfolio theory, relative strength, return factors, strategies |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 18, 2012

“Invest for the long-run” can ring hollow for a recent retiree looking to carefully manage his or her nest egg. Via an article in the New York Times by Paul Sullivan comes the following example:

How should people do the math to avoid dying broke? The answer depends as much on timing as spending.

Mark A. Cortazzo, senior partner at Macro Consulting Group, tells clients who ask this question about three fictional brothers. Each one retired with $1 million on Jan. 1 but three years apart — in 1997, 2000 and 2003. They all invested that $1 million in the Vanguard 500 Index Investor Fund.

Between when they retired and Aug. 31, 2012, each brother withdrew $5,000 a month. The brother who had been retired the longest had $1.14 million on Aug. 31. The one who retired most recently had $1.15 million left.

But the one in the middle, who began taking his monthly withdrawals in 2000, had only $160,568. The reason? The stock market went down for the first three years he was retired, and then plummeted again in 2008. He had to sell more shares to get $5,000 each month.

“Most clients say, ‘I don’t mind dying broke if I’m bouncing my last check to the undertaker,” Mr. Cortazzo said. “But I don’t want to run out at 80 if I’m going to live to 95.”

I can’t think of a better argument for employing our Global Macro strategy as part of the solution than this. Global tactical asset allocation seeks to be adaptive enough to respond to these types of adverse market conditions. The reality is that most recent retirees are in danger of running out of money in one of two ways: losing a substantial amount of money in a bear market or failing to earn enough of a return on their money to keep up with inflation. I think Global Macro does an effective job of balancing those two risks.

To view a video on our Global Macro strategy, click here.

Click here and here for disclosures. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process | Tagged: Tactical Asset Allocation |

Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process | Tagged: Tactical Asset Allocation |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Andy Hyer

October 16, 2012

The current list of things for investors to be concerned about include the fiscal cliff, European economic woes, and a Chinese slowdown. There will always be something. However, George Perry’s advice published at Real Clear Markets this morning seems to be solid:

So how worried should people be about the stock market? Nothing now on the horizon suggests that money invested in stocks today will look like a bad investment five years from now. But it would not be too surprising if stocks fell in this environment. Anyone who cannot afford a decline because they have a near term need for their capital should realize they are risking losses in stocks. They always are.

But now seems as good a time as any to be in the market for long term investors, like those who are saving for college or for retirement. Even such long term investors will be tempted, at times, to get out of the market temporarily. That is understandable but it risks reducing long term performance. As Warren Buffet has observed, nobody is likely to invest well based on what he reads in the paper each morning. And the economic risks discussed here have been, and will be, in the papers daily.

And what is most important: in order to time markets well once, you have to be right twice. First, knowing when to get out, and then knowing when to get back in.

This in no way negates the need for a well thought-out investment plan that seeks to manage risk, but I do think that it puts current risks in perspective.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Thought Process |

Thought Process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Andy Hyer

October 12, 2012

The topic of interest rates is of concern to investors for a couple of reasons. Savers are interested in finding out when interest rates might rise and they might earn more than 0% on their accumulated capital, and bond investors would like some kind of early warning if there is trouble ahead. I’ve seen lots of opinions on this, and they’ve mostly all been wrong. My personal answer to the question about when interest rates would rise would have been something like “2009,” which explains why 1) I am not a prominent interest rate forecaster and why 2) everyone should use a systematic investment process (as we do)!

To attempt to answer the interest rate question, Eddy Elfenbein of Crossing Wall Street stepped in in a way I particularly admire—with actual data, not just opinions. He showed two competing interest rate models developed by Greg Mankiw at Harvard and Paul Krugman at Princeton. Although the coefficients are slightly different, it turns out that their models are pretty similar. I’ve shown the two graphs below.

Mankiw Interest Rate Model

Krugman Interest Rate Model

Source: Crossing Wall Street (click on images to enlarge)

Up until the recent financial crisis, the forecast fit the data rather well for both models. That is to be expected, since the model is derived from the data and each modeler is searching for the best fit equation. Both models show that, given the past behavior of interest rates in relation to the variables they use (core inflation and unemployment), current interest rates should be negative! The Fed seems to be coping with this situation by holding rates at zero and using quantitative easing to simulate negative rates.

What will make these models suggest that interest rates should start to move higher? If core inflation increases and the unemployment rate begins to decline, both of these models would call for higher rates. For Krugman’s model, for example, core inflation would have to rise to 2.5% (from the current 1.8% level; I used PCE excluding food and energy), while unemployment would need to decline to 7.5% from 7.8%. (Or it could be a different combination that was mathematically equivalent.) For Mankiw’s model to call for higher rates, only a slight increase in inflation or a drop in unemployment would be needed.

If the economy continues to plug along with slow growth, low inflation, and relatively high unemployment, both of these models would continue to suggest that negative rates are needed to revive the economy.

So much for theory. In reality, many considerations go into setting the Fed Funds rate. Watching the behavior of inflation and unemployment probably enters into it, but I’m guessing the Fed is examining other data as well. From the outside, perhaps the best thing we can do is monitor the relative strength of bonds versus other asset classes to get a handle on the expectation for interest rates.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: bond market, inflation, interest rates, systematic investment process |

Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: bond market, inflation, interest rates, systematic investment process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 11, 2012

From time to time, I’ve written about karma boomerang: the harder you try to avoid getting nailed, the more likely it is that you’ll get nailed by exactly what you are trying to avoid. This concept came up again in the area of retirement income in an article I saw at AdvisorOne. The article discussed a talk given by Tim Noonan at Russell Investments. The excerpt in question:

In [Noonan's] talk, “Disengagement: Creating the Future You Fear,” he observed that lack of engagement in retirement planning is leading people toward the very financial insecurity they dread. What they need to know, and are not finding out, is simply whether they’ll have enough money for their needs.

I added the bold. This is a challenge for investment professionals. Individuals are not likely on their own to go looking for their retirement number. They are also not likely to go looking for you, the financial professional. They may realize they need help, but are perhaps intimidated to seek it—or fearful of what they might find out if they do investigate.

Retirement income is probably not an area where you want to tempt karma! Retirement income is less secure than ever for many Americans, due to under-funded pension plans, neglected 401k’s, and a faltering Social Security safety net. The only way to secure retirement income for investors is to reach out to them and get them engaged in the process.

Mr. Noonan, among other suggestions, mentioned the following:

- “Personalization” is tremendously appealing. “Tailoring” may be an even more useful term, since “people don’t mind if the tailor reuses the pattern,” Noonan explained. They may even enjoy feeling part of an elite group.

- “Tactical investing” is viewed positively. “People know they should be more adaptive, but they aren’t sure what of,” said Noonan. Financial plans should adapt to the outcomes they’re producing, not to hypothetical market forecasts.

Perhaps personalization and tactical investing can be used as hooks to get clients moving. To reach their retirement income goals, they are going to need to save big and invest intelligently, but none of that will happen if they aren’t engaged in the first place.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  From the MM, Investor Behavior, Retirement/Saving, Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process | Tagged: 401k, investor behavior, karma, Tactical Asset Allocation |

From the MM, Investor Behavior, Retirement/Saving, Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process | Tagged: 401k, investor behavior, karma, Tactical Asset Allocation |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 9, 2012

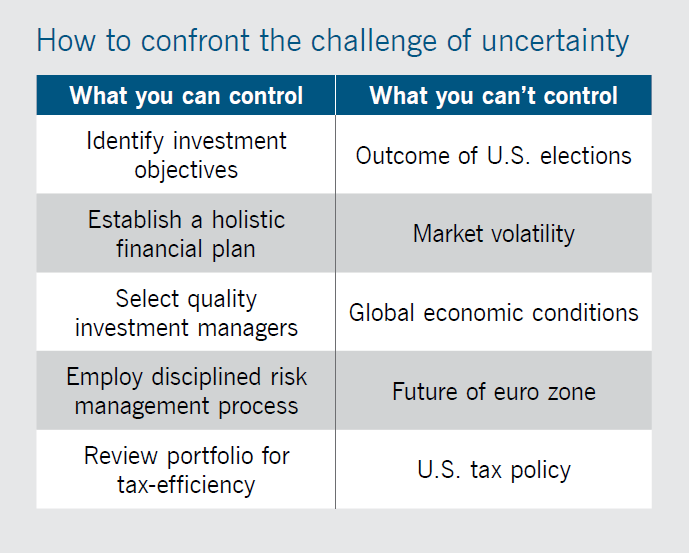

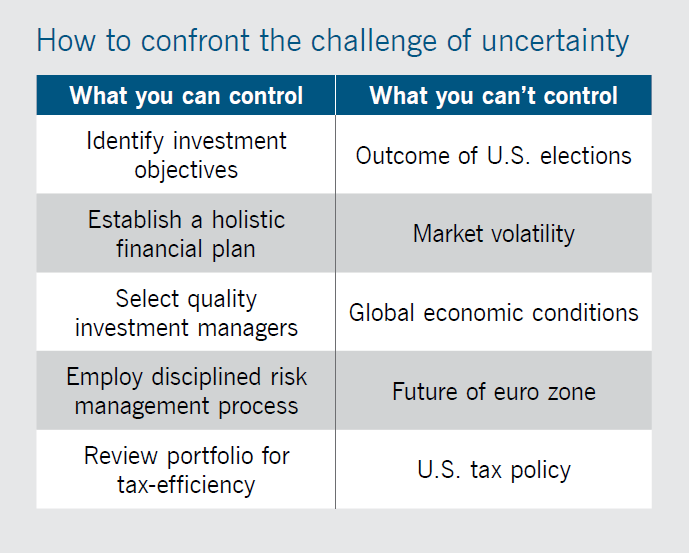

Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference—-Reinhold Niebuhr

Serenity is in short supply in the investment community! Capital Group/American Funds recently posted a fantastic commentary on uncertainty, pointing out that investors are much better off if they focus on what they can control and don’t sweat the other stuff. Here are some excerpts that struck me—but you should really read the whole thing.

Powerless. That’s how a lot of investors feel. In a recent Gallup poll, 57% of investors said they feel they have little or no control over their efforts to build and maintain their retirement savings. What’s causing them to feel so lost? According to 70% of those polled, the most important factor affecting the investment climate is something they can’t control, the federal budget deficit.

On the flip side, among investors with a written financial plan having specific goals or targets, the poll showed 80% of nonretirees and 88% of retirees said their plan gives them the confidence to achieve their financial goals. It seems like some investors have figured out what they can control and what they can’t.

Life for investors would be simpler if there were a handy timetable by which these issues would be resolved in a quick and orderly fashion. But successful investors know they can’t control the outcome of the euro-zone summits or American fiscal debates, much less plug politics into a spreadsheet.

They can, however, review their goals, manage risk, be mindful of valuation and yield and remember that diversification may matter now more than ever. It’s easy to overlook in such a challenging environment, but unsettled times can also offer opportunities for long-term investors. In the midst of uncertainty, there are companies with strong balance sheets, smart management and innovative products that continue to thrive, and whose shares may be attractively valued.

All true! We’ve written before about what an important investment attribute patience is. Maybe in some important way, serenity contributes to patience. It’s hard to be patient when you’re worried about everything, especially things you have no control over! They even include a handy-dandy graphic with suggested responses to all of those things disturbing your serenity.

Source: American Funds Distributors (click on image to enlarge)

At some level, perhaps we are all control freaks. Unfortunately for us, in a relationship with the market, it’s the market that is in control! We can’t control market events, but we can control our responses to those events. Finding healthy ways to manage market anxiety is a primary focus for every successful investor.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  From the MM, Investor Behavior, Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: decision-making, investor behavior, patience, serenity |

From the MM, Investor Behavior, Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: decision-making, investor behavior, patience, serenity |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 8, 2012

Inflation has been a big fear in the investment community for a few years now, but so far nothing has happened. An article at AdvisorOne suggests that the onset of inflation can sometimes be rapid and unexpected.

Someday, in the possibly near future, you will suddenly be paying $10 for a gallon of milk and wondering how the heck it happened so fast.

That is the strange and terrible way of inflation, said State Street Global senior portfolio manager Chris Goolgasian in a panel talk on Thursday at Morningstar ETF Invest 2012. Inflation has a way of appearing to be a distant threat before it sneaks up suddenly and starts driving prices through the roof.

Quoting from Ernest Hemingway’s novel “The Sun Also Rises,” Goolgasian took note of a passage where a man is asked how he went bankrupt. “Two ways,” the man answered. “Gradually, then suddenly.”

“The danger is in the future, and it’s important to manage portfolios for the future,” Goolgasian concluded. “Real assets can give you some assurance against that chance.”

That’s good to know—but which real assets, and when? After all, Japanese investors have probably been waiting for the inflation bogeyman for the last two decades. This is one situation in which tactical asset allocation driven by relative strength can be a big help. If you monitor a large number of asset classes continuously, you can identify when any particular real asset starts to surge in relative performance.

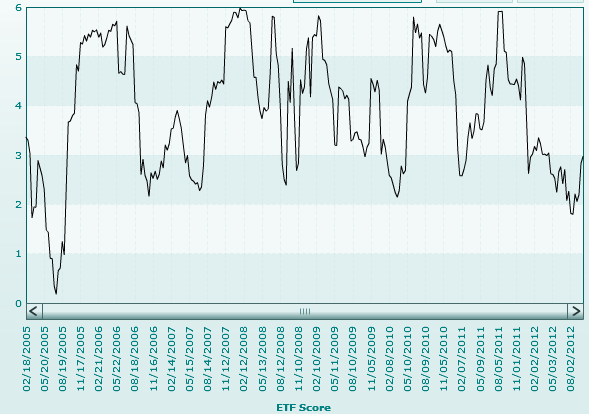

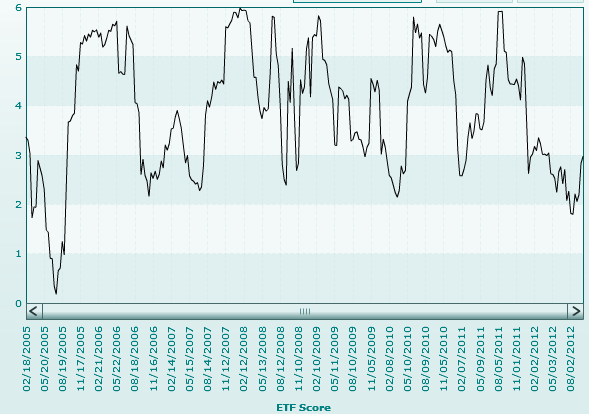

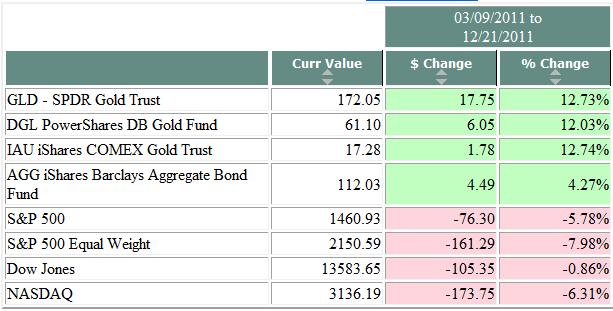

For example, on the Dorsey Wright database, the last extended run that gold had as a high relative strength asset class (ETF score > 3) was from 3/9/2011 to 12/21/2011. Below, I’ve got a picture of the ETF score chart, along with a performance snip during that same period. Perhaps because of investor concern about inflation—misplaced, as it turned out—gold outperformed fixed income over that stretch of time.

ETF Score for GLD

2011 Performance Snip

Source: Dorsey Wright (click on images to enlarge)

There’s no guarantee that gold will be an inflation hedge, of course. We never know what asset class will become strong when investors fear future inflation. Next time around it could be real estate, Swiss francs, TIPs, or energy stocks—or nothing. There are so many variables impacting performance that it is impractical (and impossible) to account for them all. However, relative strength has the simple virtue of pointing out—based on actual market performance—where the strength is appearing.

Investment history sometimes seems to be a never-ending cycle of discredited themes, but those themes can drive the market quite powerfully until they are discredited. (Remember the “new era” of the internet? Or how ”peak oil” was so compelling with crude at $140/barrel?) It’s helpful to know what those themes are, whether you are trying to take advantage of them or just trying to get out of the way.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Markets, Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process | Tagged: inflation, investor, relative strength, Tactical Asset Allocation |

Markets, Tactical Asset Alloc, Thought Process | Tagged: inflation, investor, relative strength, Tactical Asset Allocation |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 5, 2012

More money has been lost reaching for yield than at the point of a gun—Raymond Devoe

According to a recent article in the Wall Street Journal, desperate investors are reaching for yield, this time in the high-yield bond market. The less-polite name for these securities is junk bonds. Why do investors love them so? Well, they pay out fat yields—but, of course, they come with commensurate risks. And there are already warning signs in the market.

So much money has flooded into the junk-bond market from yield-hungry investors that weaker and weaker companies are able to sell bonds [they say]. Credit ratings of many borrowers are lower and debt levels are higher, making defaults more likely. And with yields near record lows, they add, investors aren’t being compensated for that risk.

Also worrying money managers is that some new sales have similar hallmarks to those that preceded the financial crisis in 2008. Petco Animal Supplies Inc. and Emergency Medical Services Corp. recently offered to sell bonds that let them pay interest in the form of more bonds, instead of cash, a common provision before the crisis.

Skeptics note that now weaker companies are the ones borrowing. The portion of new bonds sold by high-yield companies with credit ratings of double-B and above shrank last month to 20% from an average of 30% for the year.

After three years of financial improvement, high-yield companies are now weakening by some measures. Total debt for all high-yield companies rose 7.2% in the 12 months through June—the largest rise since 2008—while cash on their balance sheet fell 2.3%, according to research by Morgan Stanley. S&P downgraded 45% more companies than it upgraded in 2012, reversing the trend of 2010 and 2011. And companies are offering investors fewer protections than usual.

Now, this is just supply and demand at work. Investors want yield and companies are happy to oblige them, especially if they are willing to buy really junky securities.

The problem is that, from time to time, investors forget that investing is about total return, not just yield. An 8% yield with a 20% capital loss still puts you in the hole. Likewise, buying a stock that appreciates 20% but that does not pay a dividend still puts you way ahead of the game. When you go to the store to buy groceries, the store owner does not care if the money comes from labor, dividends, interest, or capital gains.

Money is money, however you make it. You’re probably better off—and safer—with a healthy total return from a well-diversified portfolio than you are reaching for yield.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: diversification, high-yield bonds, investor behavior, junk bonds, total return, yield |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Thought Process | Tagged: diversification, high-yield bonds, investor behavior, junk bonds, total return, yield |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 5, 2012

Well, not really the world-just the Russell Mid-Cap Growth Index. I took a look at valuation measures for PDP (the Powershares ETF version of the DWA Technical Leaders) versus its peer group, according to Morningstar. (Their data is as of 8/31/2012.) Morningstar’s peer group is a moving target, but right now they have PDP benchmarked against the Russell Mid-Cap Growth Index. As you would expect, most of the valuation measures are pretty similar, since Morningstar is intentionally looking for the index that PDP is most like at the moment. There is one measure, though, where PDP is massively different. See if you can guess what it is:

Source: Morningstar (click on image to enlarge)

While most measures are similar, the PDP constituents have growth in cash flow that is double the peer group. That appears to be a prized attribute at the present time and may account for part of the reason that PDP’s holdings have high relative strength.

Sometimes different attributes stand out when I’ve looked at these measures in the past. For example, one time I noted that while the valuations of the PDP holdings were roughly similar to the peer group, the earnings growth rates were significantly higher.

Looking at valuation and growth measures often surprises investors unfamiliar with relative strength. Their guess is usually that “momentum stocks” are puffed up and have lousy valuation metrics. That’s usually not the case. More often, stocks with high relative strength are simply “best in class.”

High relative strength stocks are usually strong for a reason, and that reason is usually strong fundamentals.

See www.powershares.com for more information.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Markets, Thought Process |

Markets, Thought Process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 3, 2012

Investors are interesting creatures. Studies of fund flows show that investors tend to buy near peaks and to sell near low points. This year investors have been piling into bond funds. Yet when the Wall Street Journal ran an online poll to ask investors what their biggest investing mistake had been, it was this: too much caution. And it wasn’t even close—excessive caution won out by a large margin. (Of course, buying near the peak had a decent second-place showing.) Here’s the accompanying graphic:

Source: Wall Street Journal (click on image to enlarge)

I find it fascinating that investors in aggregate report that caution has been their biggest mistake, all the while piling into bond funds over the past few years as the equity market had spectacular returns!

Investing for comfort is generally a poor idea. Markets are inherently uncomfortable—if you’re comfortable, in other words, you’re probably not doing it right.

Being too cautious is an insidious problem. Individual investors can end up with sub-par returns if they don’t expose their portfolio to growth assets. Growth assets tend not to be very comfortable. While volatility levels can be reduced somewhat by good diversification, it’s still the uncomfortable assets that will generate much of your return over time. When you put together an asset allocation, it should have as much exposure to growth as possible, given the constraints of the individual client.

Why, then, is caution so prized? I suspect it is because people wish to have positive self-regard and because mistakes reduce that self-regard for many people. They err on the side of caution because they are trying to avoid mistakes. While this may be psychologically wonderful, it is counterproductive in financial markets. In fact, research shows that you are actually more likely to make a mistake through excessive caution than from being overly aggressive. Investors, judging from the poll results, seem to understand this in retrospect—although maybe not prospectively.

If you invest, you are going to make mistakes. There is no way to sugarcoat it. Not everything is going to work out. We think the best way to avoid excessive caution is to adopt a systematic investment process. If you have a systematic way to determine what to buy, when to buy it, and when to sell it, you may be less likely to pull your punches.

11 Comments |

11 Comments |  Investor Behavior, Markets, Thought Process |

Investor Behavior, Markets, Thought Process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Mike Moody

October 2, 2012

Front and center on Yahoo! Finance this morning is the following headline:

Arguably the headline is hyperbolic, but this is just your daily reminder why you need to use technical analysis—money is made by investing in the market as it actually is, not how we think it should be.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Markets, Thought Process |

Markets, Thought Process |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Andy Hyer

September 27, 2012

Adam Davidson’s article “Hey, Big Saver!” in the New York Times is an excellent summary of the competing arguments on the merits of QE3. There truly are compelling arguments for why this will work and there are compelling arguments why it won’t. Effectiveness aside, Bernanke has made his intentions perfectly clear:

When Bernanke announced that the Fed would be investing in the mortgage market indefinitely, he signaled that he’s had it with short-term fixes. His Fed is committed, he said, to taking extraordinary measures until unemployment goes down. In Fed-speak, Q.E. 3 is a clear message to banks, investors and private companies that the economy is going to grow, and the riskiest thing they can do is to hold on to their cash and riskless securities and watch their competitors profit.

Are his policies working or not? This is why I love technical analysis. Rather than get caught up in theoretic debates, technical analysis cuts to the chase and asks a different question: What stocks, sectors, and asset classes have the best relative strength? Based on that information, relative strength investors can orient their portfolio to capitalize on those trends.

Investors are not interested in winning theoretical debates. Investors are interested in making money! Rather than focusing on what the Fed, Congress, the President, the ECB, banks, consumers, economists, investment strategists, your brother-in-law… have to say about what is going to happen in the market, take the pragmatist’s approach and let relative strength dictate your investment decisions.

Source: CBS News

HT: Real Clear Markets

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Thought Process | Tagged: decision-making, relative strength |

Thought Process | Tagged: decision-making, relative strength |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by:

Andy Hyer