John Rekenthaler at Morningstar launched into a spirited defense of buy and hold investing over the weekend. His argument is essentially that since markets have bounced back since 2009, buy and hold is alive and well, and any arguments to the contrary are flawed. Here’s an excerpt:

There never was any logic behind the “buy-and-hold is dead” argument. Might it have lucked into being useful? Not a chance. Coming off the 2008 downturn, the U.S. stock market has roared to perhaps its best four and a half years in history. It has shone in absolute terms, posting a cumulative gain of 125% since spring 2009. It has been fabulous in real terms, with inflation being almost nonexistent during that time period. It’s been terrific in relative terms, crushing bonds, cash, alternatives, and commodities, and by a more modest amount, beating most international-stock markets as well. This is The Golden Age. We have lived The Golden Age, all the while thinking it was lead.

Critics will respond that mine is a bull-market argument. That’s backward. “Buy-and-hold is dead” is the strategy that owes its existence to market results. It only appears after huge bear markets, and it only looks good after such markets. It is the oddity, while buy-and-hold is the norm.

Generally, I think Morningstar is right about a lot of things—and Rekenthaler is even right about some of the points he makes in this article. But in broad brush, buy and hold has a lot of problems, and always has.

Here’s where Rekenthaler is indisputably correct:

- “Buy and hold is dead” arguments always pop up in bear markets. (By the way, that says nothing about the accuracy of the argument.) It’s just the time that anti buy-and-holders can pitch their arguments when someone might listen. In the same fashion, buy and hold arguments are typically made after a big recovery or in the midst of a bull market—also when people are most likely to listen. Everyone has an axe to grind.

- Buy and hold has looked good in the past, compared to forecasters. As he points out in the article, it is entirely possible to get the economic forecast correct and get the stock market part completely wrong.

- The 2008 market crash gave the S&P 500 its largest calendar year loss in 77 years. No doubt.

The truth about buy and hold, I think, is considerably more nuanced. Here are some things to consider.

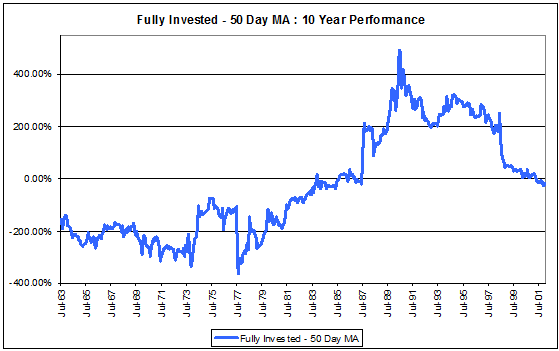

- The argument for buy and hold rests on hindsight bias. Historical returns in the US markets have been among the strongest in history over very long time periods. That’s why US investors think buy and hold works. If buy and hold truly works, what about Germany, Argentina, or Japan at various time periods? The Nikkei peaked in 1989. Almost 25 years later, the market is still down significantly. Is the argument, then, that only the US is special? Is Mr. Rekenthaler willing to guarantee that US returns will always be positive over some time frame? I didn’t think so. If not, then buy and hold is not a slam dunk either.

- Individual investors have time frames. We only live so long. A buy and hold retiree in 1929 or 1974 might be dead before they got their money back. Same for a Japanese retiree in 1989. Plenty of other equity markets around the world, due to wars or political crises, have gone to zero. Zero. That makes buy and hold a difficult proposition—it’s a little tough mathematically to bounce back from zero. (In fact, the US and the UK are the only two markets that haven’t gone to zero at some point in the last 200 years.) And plenty of individual stocks go to zero. Does buy and hold really make sense with stocks?

- Rejecting buy and hold does not have the logical consequence of missing returns in the market since 2009. For example, a trend follower would be happily long the stock market as it rose to new highs.

- Individual investors, maddeningly, have very individual tolerances for volatility in their portfolios. Some investors panic too often, some too late, and a very few not at all. How that works out is completely path dependent—in other words, the quality of our decision all depends on what happens subsequently in the market. And no one knows what the market will do going forward. You don’t know the consequences of your decision until some later date.

- In our lifetimes, Japan. It’s funny how buy and hold proponents either never mention Japan or try to explain it away. “We are not Japan.” Easy to say, but just exactly how is human nature different because there is an ocean in between? Just how is it that we are superior? (Because in 1989, if you go back that far, there was much hand-wringing and discussions of how the Japanese economy was superior!)

Every strategy, including buy and hold, has risks and opportunity costs. Every transaction is a risk, as well as an implicit bet on what will happen in the future. The outcome of that bet is not known until later. Every transaction, you make your bet and you take your chances. You can’t just assume buy and hold is going to work forever, nor can you assume it will stop working. Arguments about any strategy being correct because it worked over x timeframe is just a good example of hindsight bias. Buy and hold doesn’t promise good returns, just market returns. Going forward, you just don’t know—nobody knows. Yes, ambiguity is uncomfortable, but that’s the way it is.

That’s the true state of knowledge in financial markets: no one knows what will happen going forward, whether they pretend to know or not.