This is the title of a nice article by Brett Arends at Marketwatch. He points out that a lot of our assumptions, especially regarding risk, are open to question.

Risk is an interesting topic for a lot of reasons, but principally (I think) because people seem to be obsessed with safety. People gravitate like crazy to anything they perceive to be “safe.” (Arnold Kling has an interesting meditation on safe assets here.)

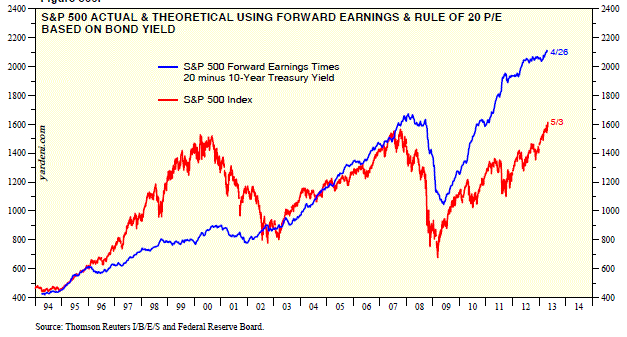

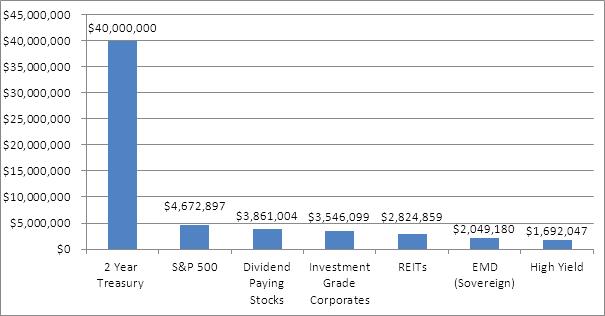

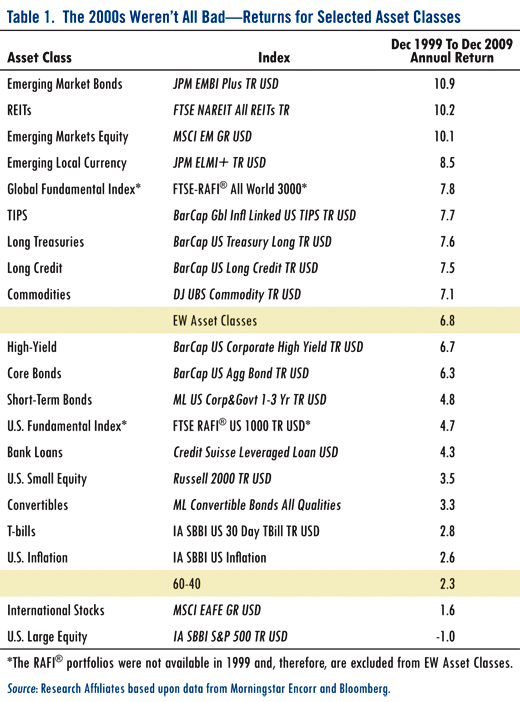

Risk, though, is like matter–it can neither be created nor destroyed. It just exists. When you buy a safe investment, like a U.S. Treasury bill, you are not eliminating your risk; you are just switching out of the risk of losing your money into the risk of losing purchasing power. The risk hasn’t gone away; you have just substituted one risk for another. Good investing is just making sure you’re getting a reasonable return for the risk you are taking.

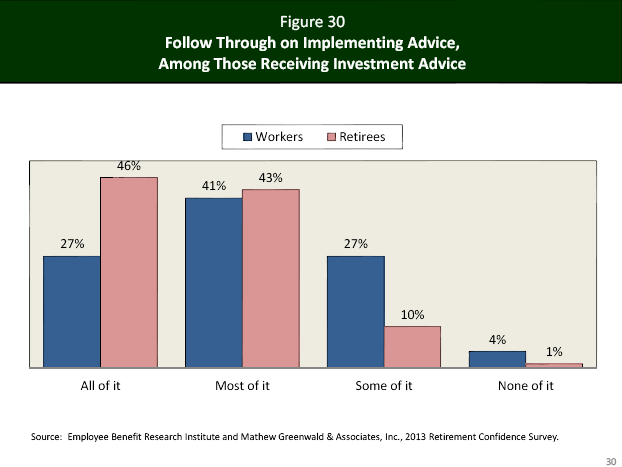

In general, investors–and people generally–are way too risk averse. They often get snookered in deals that are supposed to be “low risk” mainly because their risk aversion leads them to lunge at anything pretending to be safe. Psychologists, however, have documented that individuals make more errors from being too conservative than too aggressive. Investors tend to make that same mistake. For example, nothing is more revered than a steady-Eddie mutual fund. Investors scour magazines and databases to find a fund that (paradoxically) is safe and has a big return. (News flash: if such a fund existed, you wouldn’t have to look very hard.)

No one goes looking for high-volatility funds on purpose. Yet, according to an article, Risk Rewards: Roller-Coaster Funds Are Worth the Ride at TheStreet.com:

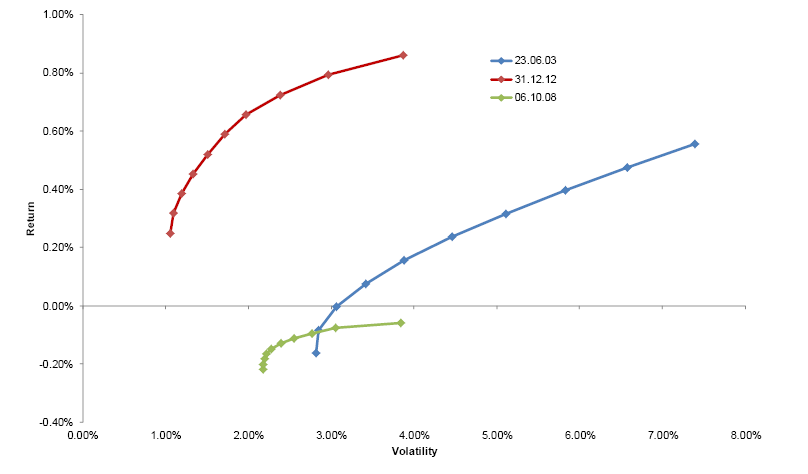

Funds that post big returns in good years but also lose scads of money in down years still tend to do better over time than funds that post slow, steady returns without ever losing much.

The tendency for volatile investments to best those with steadier returns is even more pronounced over time. When we compared volatile funds with less volatile funds over a decade, those that tended to see big performance swings emerged the clear winners. They made roughly twice as much money over a decade.

That’s a game changer. Now, clearly, risk aversion at the cost of long-term returns may be appropriate for some investors. But if blind risk aversion is killing your long-term returns, you might want to re-think. After all, eating Alpo is not very pleasant and Maalox is pretty cheap. Maybe instead of worrying exclusively about volatility, we should give some consideration to returns as well.

—-this article originally appeared 3/3/2010. A more recent take on this theme are the papers of C. Thomas Howard. He points out that volatility is a short-term factors, while compounded returns are a long-term issue. By focusing exclusively on volatility, we can often damage long term results. He re-defines risk as underperformance, not volatility. However one chooses to conceptualize it, blind risk aversion can be dangerous.