Andrew Ang of Columbia Business School has an important new paper out on SSRN. In it, he discusses mean variance optimization, the cornerstone of Modern Portfolio Theory. Unlike many other treatments in which portfolio construction through mean variance optimization is taken as gospel, Mr. Ang actually tests mean variance optimization against a wide variety of other diversification methods. This is the first article that I have seen that actually tries to put numbers to mean variance optimization. Here’s how he lays out his horserace:

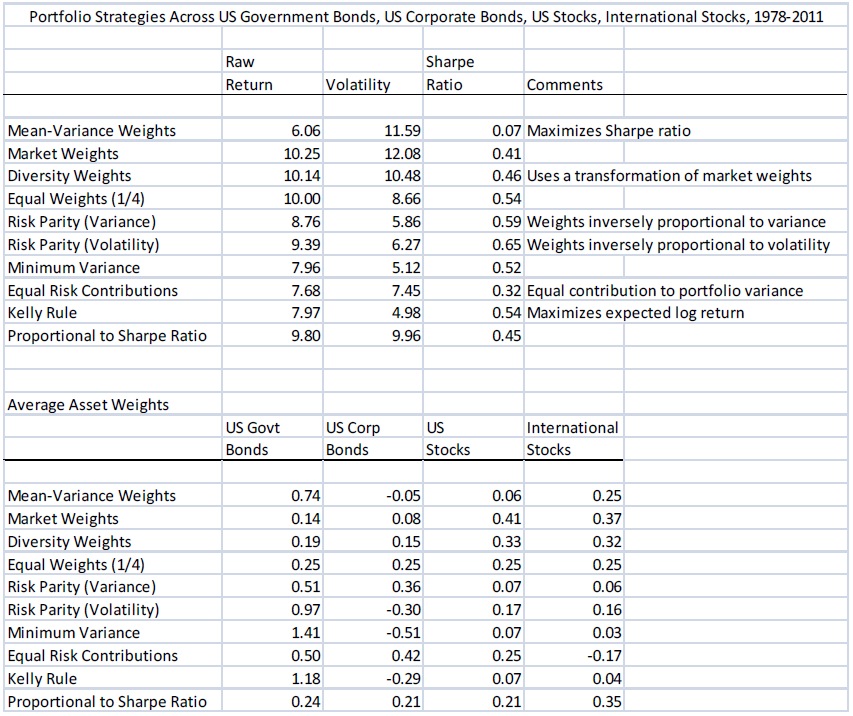

I take four asset classes: U.S. government bonds (Barcap U.S. Treasury), U.S. corporate bonds (Barcap U.S. Credit), U.S. stocks (S&P 500), and international stocks (MSCI EAFE), and track performance of various portfolios from January 1978 to December 2011. The data are sampled monthly. The strategies implemented at time t are estimated using data over the past five years, t-60 to t. The first portfolios are formed at the end of January 1978 using data from January 1973 to January 1978. The portfolios are held for one month, and then new portfolios are formed at the end of the month. I use one-month T-bills as the risk-free rate. In constructing the portfolios, I restrict shorting down to -100% on each asset.

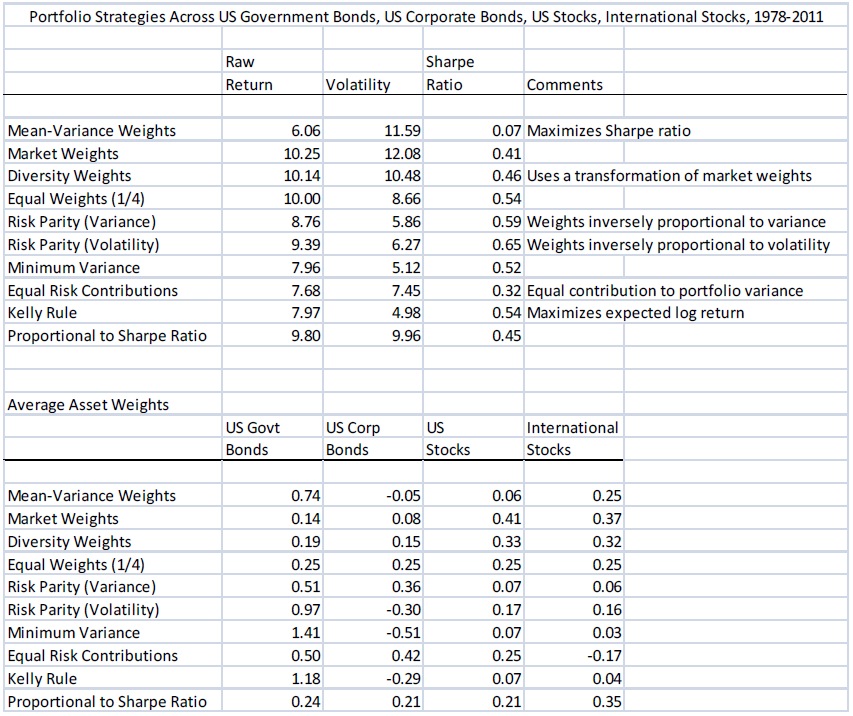

He tests a wide variety of diversification methods. As usual, simple is often better. Here’s his synopsis of the results:

Table 14 reports the results of the horserace. Mean-variance weights perform horribly. The strategy produces a Sharpe ratio of just 0.07 and it is trounced by all the other strategies. Holding market weights does much better, with a Sharpe ratio of 0.41. This completely passive strategy outperforms the Equal Risk Contributions and the Proportional to Sharpe Ratio portfolios (with Sharpe ratios of 0.32 and 0.45, respectively). Diversity Weights tilt the portfolio towards the asset classes with smaller market caps, and this produces better results than market weights. The simple Equal Weight strategy does very well with a Sharpe ratio of 0.54. What a contrast with this strategy versus the complex mean-variance portfolio (with a Sharpe ratio of 0.07)! The Equal Weight strategy also outperforms the market portfolio (with a Sharpe ratio of 0.41). De Miguel, Garlappi and Uppal (2009) find that the simple 1/N rule outperforms a large number of other implementations of mean-variance portfolios, including portfolios constructed using robust Bayesian estimators, portfolio constraints, and optimal combinations of portfolios which I covered in Section 4.2. The 1/N portfolio also produces a higher Sharpe ratio than each individual asset class position.

That’s a lot to absorb. If we remove the academic flourishes, what he is saying is that mean variance optimization is dreadful and is easily outperformed by simply equal-weighting the asset classes. He references Table 14 of his paper, which I have reproduced below.

Table 14 Source: Andrew Ang/SSRN

(click to enlarge to full size)

(He points out later in the text that although risk parity approaches generate a slightly higher Sharpe ratio than equal weighting, it is mostly due to bonds performing so well over the 1978-2011 time period, a period of sharply declining interest rates. Like most observers of markets, he would be surprised to see interest rates decline dramatically from here, and thus thinks that the higher Sharpe ratios may be unsustainable. Mr. Ang also mentions in the article that using a five-year estimation period isn’t ideal, but that using 20-year or 50-year data is no better.)

I find it ironic that although mean variance optimization is designed to maximize the Sharpe ratio—to generate the most return for the least volatility—in real life it generates the worst results. As Yogi Berra said, in theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they aren’t!

Mr. Ang also asks and answers the question about why mean variance optimization does so poorly.

The optimal mean-variance portfolio is a complex function of estimated means, volatilities, and correlations of asset returns. There are many parameters to estimate. Optimized mean-variance portfolios can blow up when there are tiny errors in any of these inputs. In the horserace with four asset classes, there are just 14 parameters to estimate and even with such a low number mean-variance does badly. With 100 assets, there are 5,510 parameters to estimate. For 5,000 stocks (approximately the number listed in U.S. markets) the number of parameters to estimate is over 12,000. The potential for errors is enormous.

I put the fun part in bold. Tiny errors in estimating returns, volatilities, or correlations can cause huge problems. Attempting to estimate even 14 parameters ended in abject failure. We’ve written numerous pieces over the years about the futility of forecasting, yet this is exactly the process that Harry Markowitz, the father of Modern Portfolio Theory, would have you take!

Good luck with that.

To me, the implications are obvious. Diversification is always important, as it is a mathematical truism that combining any two assets that are not perfectly correlated will reduce volatility. But simple is almost always better. Mr. Ang draws the same conclusion. He writes:

Common to all these portfolio strategies is the fact that they are diversified. This is the message you should take from this chapter. Diversification works. Computing optimal portfolios using full mean-variance techniques is treacherous, but simple diversification strategies do very well.

The “simple is better” idea is not limited to asset class diversification. I think it also extends to diversification by investment strategy, like relative strength or value or low volatility. There’s an underlying logic to it—simple is better, because simple is more robust.

Some investors, it seems, are always chasing the holy grail or coming up with complicated theories that are designed to outperform the markets. In reality, you can probably dispense with all of the complex theory and use common sense. Staying the course with an intelligently diversified portfolio over the long term is probably the best way to reach your investing goals.