Marshall Jaffe wrote an excellent article on investment process versus investment performance in the most recent edition of ThinkAdvisor. I think it is notable for a couple of reasons. First, it’s pithy and well-written. But more importantly, he’s very blunt about the problems of focusing only on investment performance for both clients and the industry. And make no mistake—that’s how the investment industry works in real life, even though it is a demonstrably poor way to do things. Consider this excerpt:

We see the disclaimer way too often. “Past performance is no guarantee of future results.” It is massively over-used—plastered on countless investment reports, statements and research. It’s not simply meaningless; it’s as if it’s not even there. And that creates a huge problem, because the message itself is really true: Past performance has no predictive value.

Since we are looking for something that does have predictive value—all the research, experience and hard facts say: Look elsewhere.

This is not a controversial finding. There are no fringe groups of investors or scholars penning op-ed pieces in the Wall Street Journal shooting holes in the logic of this reality. Each year there is more data, and each year that data reconfirms that past performance is completely unreliable as an investment tool. Given all that, you would think it would be next to impossible to find any serious investors still using past performance as a guideline. Indeed, that would be a logical conclusion.

But logical conclusions are often wrong when it comes to understanding human behavior. Not only does past performance remain an important issue in the minds of investors, for the vast majority it is the primary issue. In a study I referred to in my August column, 80% of the hiring decisions of large and sophisticated institutional pension plans were the direct result of outstanding past performance, especially recent performance.

The truth hurts! The bulk of the article discusses why investors focus on performance to their detriment and gives lots of examples of top performers that focus only on process. There is a reason that top performers focus on process—because results are the byproduct of the process, not an end in themselves.

The reason Nick Saban, our best athletes, leading scientists, creative educators, and successful investors focus on process is because it anchors them in reality and helps them make sensible choices—especially in challenging times. Without that anchor any investor observing the investment world today would be intimidated by its complexity, uncomfortable with its volatility and (after the meltdown in 2008) visibly fearful of its fragility. Of course we all want good returns—but those who use a healthy process realize that performance is not a goal; performance is a result.

Near the end of the article, I think Mr. Jaffe strikes right to the core of the investment problem for both individual investors and institutions. He frames the right question. Without the right question, you’re never going to get the right answer!

In an obsessive but fruitless drive for performance too many fund managers compromise the single most important weapon in their arsenal: their investment process.

Now we can see the flaw in the argument that an investor’s basic choice is active or passive. An investor indeed has two choices: whether to be goal oriented or process oriented. In reframing the investment challenge that way, the answer is self-evident and the only decision is whether to favor a mechanical process or a human one.

Reframing the question as “What is your investment process?” sidelines everything else. (I added the bold.) In truth, process is what matters most. Every shred of research points out the primacy of investment process, but it is still hard to get investors to look away from performance, even temporarily.

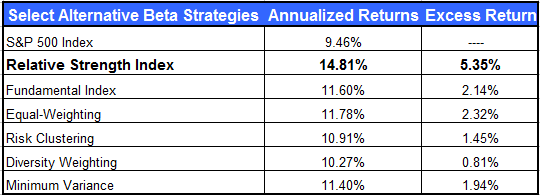

We focus on relative strength as a return factor—and we use a systematic process to extract whatever return is available—but it really doesn’t matter what return factor you use. Value investors, growth investors, or firms trying to harvest more exotic return factors must still have the same focus on investment process to be successful.

If you are an advisor, you should be able to clearly explain your investment process to a client. If you are an investor, you should be asking your advisor to explain their process to you. If there’s no consistent process, you might want to read Mr. Jaffe’s article again.

HT to Abnormal Returns