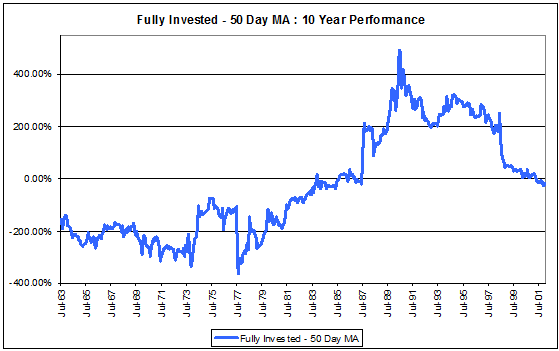

As much as investors appear to dislike stocks right now, Bob Carey of First Trust points out that the S&P; has a habit of bouncing back. The gist of his argument is contained in a nice graphic and a few paragraphs of commentary. Here’s the relevant chart:

Source: Bob Carey, First Trust (click on image to enlarge)

Although this picture is probably worth a thousand words too, his commentary is especially on point. Here’s what you are looking at:

- The time periods featured in the chart depict the annualized returns for the S&P; 500 from the index’s lowest price point following a crisis situation.

- Those crisis situations were as follows: 1973-74 (Oil Embargo); 1981 (Hyperinflation); 1987 (Crash/Black Monday); 1990 (S&L; Failures/LBOs); 2002 (Internet Bubble Burst); and 2008 (Subprime/Financial Crisis).

Amazing, isn’t it? If you had the nerve to buy during each crisis, you racked up big returns over the long run. (The recent returns have been exceptionally strong, but the time period is much shorter and hasn’t had time to include any additional bear markets.)

I find it extraordinary that the market managed 8% annual returns if you bought after the tech wreck in 2002, even after holding it all the way through the most recent financial crisis. American business is remarkably resilient and our financial markets reflect that. Even at the depths of a crisis—especially at the depths of a crisis—it makes sense of buy shares in growing businesses. Headlines and negative investor sentiment shouldn’t necessarily deter you from buying productive assets.