Investment manager selection is one of several challenges that an investor faces. However, if manager selection is done well, an investor has only to sit patiently and let the manager’s process work—not that sitting patiently is necessarily easy! If manager selection is done poorly, performance is likely to be disappointing.

For some guidance on investment manager selection, let’s turn to a recent article in Advisor Perspectives by C. Thomas Howard of AthenaInvest. AthenaInvest has developed a statistically validated method to forecast fund performance. You can (and should) read the whole article for details, but good investment manager selection boils down to:

- investment strategy

- strategy consistency

- strategy conviction

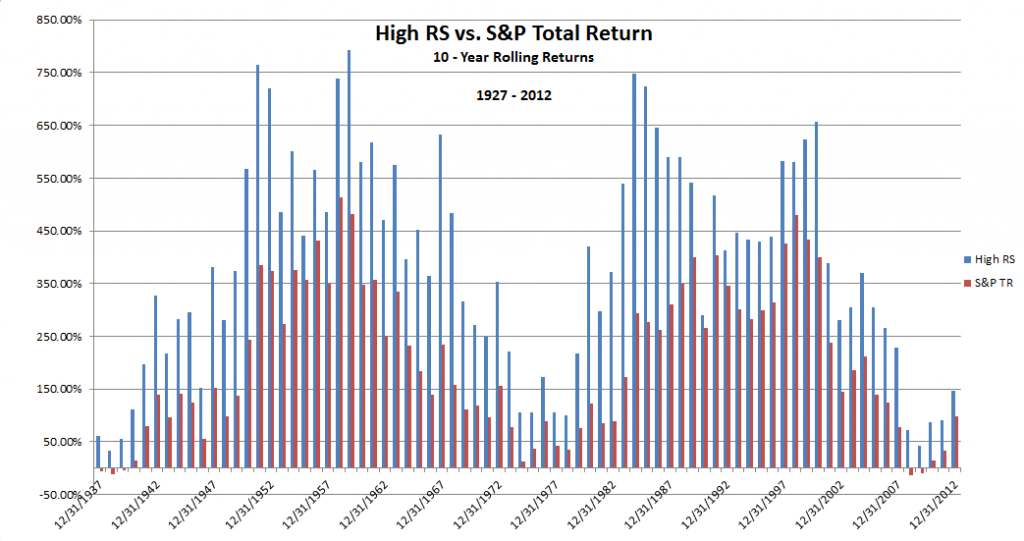

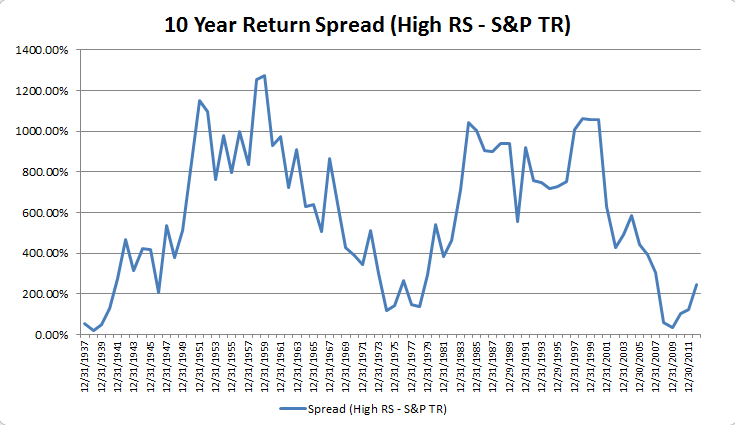

This particular article doesn’t dwell on investment strategy, but obviously the investment strategy has to be sound. Relative strength would certainly qualify based on historical research, as would a variety of other return factors. (We particularly like low-volatility and deep value, as they combine well with relative strength in a portfolio context.)

Strategy consistency is just what it says—the manager pursues their chosen strategy without deviation. You don’t want your value manager piling into growth stocks because they are in a performance trough for value stocks (see Exhibit 1999-2000). Whatever their chosen strategy or return factor is, you want the manager to devote all their resources and expertise to it. As an example, every one of our portfolio strategies is based on relative strength. At a different shop, they might be focused on low-volatility or small-cap growth or value, but the lesson is the same—managers that pursue their strategy with single-minded consistency do better.

Strategy conviction is somewhat related to active share. In general, investment managers that are willing to run relatively concentrated portfolios do better. If there are 250 names in your portfolio, you might be running a closet index fund. (Our separate accounts, for example, typically have 20-25 positions.) A widely dispersed portfolio doesn’t show a lot of conviction in your chosen strategy. Of course, the more concentrated your portfolio, the more it will deviate from the market. For managers, career risk is one of the costs of strategy conviction. For investors, concentrated portfolios require patience and conviction too. There will be a lot of deviation from the market, and it won’t always be positive. Investors should take care to select an investment manager that uses a strategy the investor really believes in.

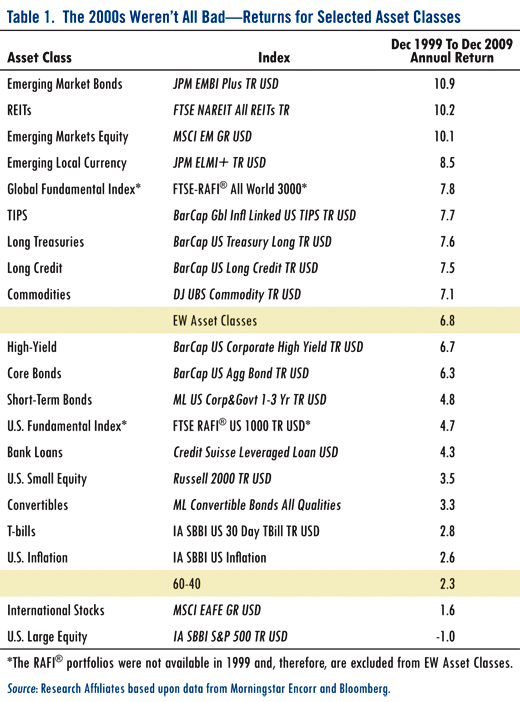

AthenaInvest actually rates mutual funds based on their strategy consistency and conviction, and the statistical results are striking:

The higher the DR [Diamond Rating], the more likely it will outperform in the future. The superior performance of higher rated funds is evident in Table 1. DR5 funds outperform DR1 funds by more than 5% annually, based on one-year subsequent returns, and they continue to deliver outperformance up to five years after the initial rating was assigned. In this fashion, DR1 and DR2 funds underperform the market, DR3 funds perform at the market, and DR4 and DR5 funds outperform. The average fund matches market performance over the entire time period, consistent with results reported by Bollen and Busse (2004), Brown and Goetzmann (1995) and Fama and French (2010), among others.

Thus, strategy consistency and conviction are predictive of future fund performance for up to five years after the rating is assigned.

The bold is mine, as I find this remarkable!

I’ve reproduced a table from the article below. You can see that the magnitude of the outperformance is nothing to sniff at—400 to 500 basis points annually over a multi-year period.

Source: Advisor Perspectives/AthenaInvest (click on image to enlarge)

The indexing crowd is always indignant at this point, often shouting their mantra that “active managers don’t outperform!” I regret to inform them that their mantra is false, because it is incomplete. What they mean to say, if they are interested in accuracy, is that “in aggregate, active managers don’t outperform.” That much is true. But that doesn’t mean you can’t locate active managers with a high likelihood of outperformance, because, in fact, Tom Howard just demonstrated one way to do it. The “active managers don’t outperform” meme is based on a flawed experimental design. I tried to make this clear in another blog post with an analogy:

Although I am still 6’5″, I can no longer dunk a basketball like I could in college. I imagine that if I ran a sample of 10,000 random Americans and measured how close they could get to the rim, very few of them could dunk a basketball either. If I created a distribution of jumping ability, would I conclude that, because I had a large sample size, the 300 people would could dunk were just lucky? Since I know that dunking a basketball consistently is possible–just as Fama and French know that consistent outperformance is possible–does that really make any sense? If I want to increase my odds of finding a portfolio of people who could dunk, wouldn’t it make more sense to expose my portfolio to dunking-related factors–like, say, only recruiting people who were 18 to 25 years old and 6’8″ or taller?

In other words, if you look for the right characteristics, you have a shot at finding winning investment managers too. This is valuable information. Think of how investment manager selection is typically done: “What was your return last year, last three years, last five years, etc.?” (I know some readers are already squawking, but the research literature shows clearly that flows follow returns pretty closely. Most “rigorous due diligence” processes are a sham—and, unfortunately, research shows that trailing returns alone are not predictive.) Instead of focusing on trailing returns, investors would do better to locate robust strategies and then evaluate managers on their level of consistency and conviction.